Born :

Died :

AMERICAN

Actor & writer

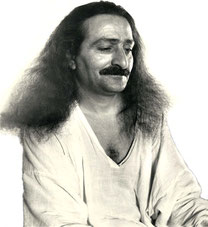

Lord Meher Volume

6, Page 1937

Baba also visited Paramount, Universal, Fox and Warner Brothers studios where he met many celebrities including the French singer Maurice Chevalier and movie producer Joseph Von Sternberg. He had a conversation with actor Will Rogers and was photographed with actress Alice Faye. In Hollywood, Baba also saw several films, one of which was Imitation of Life at the Pantages Theater on Hollywood Boulevard near Vine Street. Baba and his group took walks in the evenings. Minta once recollected, "There were the most fabulous sunsets. But they were not to be enjoyed. Baba walked terribly fast and we used to run to keep up with him."

Lord Meher Volume 18, Page 6044

The entire Dadachanji family arrived from Bombay. Remembering Chanji, Baba reminisced:

Since early morning, I have been thinking of Chanji, my constant companion and indefatigable secretary during all my travels in India and abroad. I recall the time we traveled to Hollywood with Kaka Baria when many important film stars of the time met me [1932]. Once, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford invited me to their home as their chief guest, and many came there to shake hands with me. Mary Pickford welcomed me, saying: "We feel greatly honored by your presence in our home ..." and thereafter she introduced me to all those she had invited. Among them were Gary Cooper, Charles Laughton, Marlene Dietrich, and Will Rogers who spoke with me for half an hour. And, of course, there was Tallulah Bankhead. I remember Marie Dressler especially; she took to me like a mother to her son, and invited me for dinner at her home. She fondly caressed my face saying: "My child, my child ..."

Oklahoma City - Will Rogers World Airport

Will Rogers

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| William "Will" Rogers | |

|---|---|

Will Rogers |

|

| Born |

November 4, 1879 Oologah, Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) |

| Died |

August 15, 1935 (aged 55) Point Barrow, Alaska Territory |

| Occupation |

actor, comic, columnist, radio personality |

| Political party |

Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Betty Blake (1879–1944) |

| Children |

William Vann

"Bill"

|

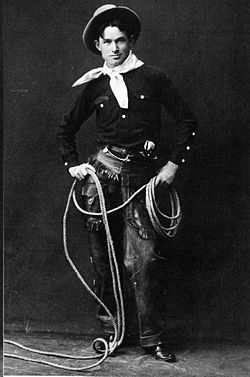

William Penn Adair "Will" Rogers (November 4, 1879 – August 15, 1935) was a Cherokee cowboy, comedian, humorist, social commentator, vaudeville performer and actor. He was the father of U.S. Representative and WWII veteran Will Rogers, Jr.

Known as Oklahoma's favorite son,[1] Rogers was born to a prominent Indian Territory family. He traveled around the world three times, made 71 movies (50 silent films and 21 "talkies"),[2] wrote more than 4,000 nationally-syndicated newspaper columns,[3] and became a world-famous figure.

By the mid-1930s, Rogers was adored by the American people, and was the top-paid movie star in Hollywood at the time. Rogers died in 1935 with aviator Wiley Post, when their small airplane crashed near Barrow, Alaska Territory.

Contents |

Early years

Will Rogers was born on the Dog Iron Ranch in Indian Territory, near present-day Oologah, Oklahoma. The house he was born in had been built in 1875 and was known as the "White House on the Verdigris River."[2] His parents, Clement Vann Rogers (1839–1911) and Mary America

Schrimsher (1838–1890), were both Cherokee, and Rogers

himself was 9/32s Cherokee.[4] Rogers quipped that his ancestors didn't come over on the Mayflower but they "met the boat."[5] Clement

Rogers was a distinguished figure in Indian Territory. A Cherokee senator and judge, he was a Confederate veteran and served as a delegate to the

Oklahoma Constitutional

Convention. Rogers County, Oklahoma is named in honor of Clement Rogers.[2] Mary Rogers was quarter-Cherokee and hereditary

member of the Paint Clan.[6] She died when Will was 11, and his father remarried less than two years after her death.[7]

Rogers was the youngest of his parents' eight children. He was named for the Cherokee leader Col. William Penn Adair.[8] Only three of his siblings, sisters Sallie Clementine, Maude Ethel, and May (Mary), survived into adulthood. The children attended Willow Hassel School in Neosho, Missouri, and later Kemper Military School in Boonville, Missouri. He ended his studies after the 10th grade. He admitted he was a poor student, saying that he "studied the Fourth Reader for ten years."[5] He was much more interested in cowboys and horses, and learned to rope and use a lariat.

After ending his brief formal studies, Rogers worked the Dog Iron Ranch for a few years. Near the end of 1901, he and a friend

left home with aspirations to work as gauchos in Argentina.[5] They

made it to Argentina in May 1902, and spent five months trying to make it as ranch owners in the Argentine pampas. Unfortunately, Rogers and his partner lost all their money, and in his words, "I was ashamed

to send home for more," so the two friends separated and Rogers sailed for South Africa. It is often claimed he took a job breaking in horses for the British Army, but the Boer War had ended three months earlier.[9] Rogers actually

got work at Piccione's ranch in Mooi River Station.[10]

When the war ended and the British Army no longer required his service, he began his show business career as a trick roper in "Texas Jack's Wild West Circus":

He (Texas Jack) had a little Wild West aggregation that visited the camps and did a tremendous business. I did some roping and riding, and Jack, who was one of the smartest showmen I ever knew, took a great interest in me. It was he who gave me the idea for my original stage act with my pony. I learned a lot about the show business from him. He could do a bum act with a rope that an ordinary man couldn't get away with, and make the audience think it was great, so I used to study him by the hour, and from him I learned the great secret of the show business—knowing when to get off. It's the fellow who knows when to quit that the audience wants more of.[9]

Grateful for the guidance but anxious to move on, Rogers quit the circus and went to Australia. Texas Jack gave him a reference letter for the Wirth Brothers Circus there, and Rogers continued to perform as a rider and trick roper, and worked on his pony act. He returned to the United States in 1904, and began to try his roping skills on the American vaudeville circuits.

Vaudeville

On a trip to New York City, Rogers was at Madison Square Garden when a wild steer broke out of the arena and began to climb into the viewing stands. Rogers quickly

roped the steer to the delight of the crowd. The feat got front page attention from the newspapers, giving him valuable publicity and an audience eager to see more. William Hammerstein came to

see his vaudeville act, and quickly signed Rogers to appear on the Victoria Roof—which was literally on a rooftop—with his pony. For the next decade, Rogers estimated he worked for fifty weeks a

year at the Roof and at the city's myriad vaudeville theaters.[9]

In 1908, Rogers married Betty Blake, and the couple had four children: Will Rogers, Jr. (Bill), Mary Amelia (Mary), James Blake (Jim), and Fred Stone.

Bill became a World War II hero, played his

father in two films, and became a member of Congress. Mary became a Broadway actress, and Jim was a newspaperman and rancher; Fred died of diphtheria at age two.[3] The family lived in New York,

but they managed to make it home to Oklahoma during the summers. In 1911, Rogers bought a 20-acre (8.1 hectare)

ranch near Claremore,

Oklahoma, which he intended to use as his retirement home, for US$500 per acre.[3]

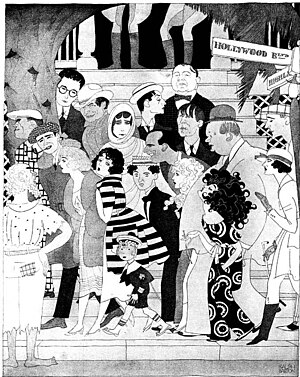

In the fall of 1915, Rogers began to appear in Florenz Ziegfeld's Midnight Frolic. The variety revue began at midnight in the top-floor night club of Ziegfeld's New Amsterdam Theatre, and drew many influential—and regular—customers. By this time, Rogers had refined his act to a science. His monologues on the news of the day followed a similar routine every night. He appeared on stage in his cowboy outfit, nonchalantly twirling his lasso, and said, "Well, what shall I talk about? I ain't got anything funny to say. All I know is what I read in the papers." He then made jokes about what he had read in that day's newspapers. The line "All I know is what I read in the papers" is often incorrectly described as Rogers's most famous punch line, when it was in fact his opening line.

His run at the New Amsterdam ran on into 1916, and Rogers's obvious popularity led to an engagement on the more famous Ziegfeld Follies. Ziegfeld saw comedians as mere 'stage-fillers' who entertained the audience while the stage was reset for the next spectacle of beautiful girls in stunning costumes. Rogers managed to not only hold his own, but achieved star status, with both his roping and his precise satire on the daily news. An editorial in the The New York Times said that "Will Rogers in the Follies is carrying on the tradition of Aristophanes, and not unworthily."[11] Rogers branched into silent films too, for Samuel Goldwyn's company Goldwyn Pictures. He made his first silent movie, Laughing Bill Hyde, filmed in Fort Lee, New Jersey, in 1918. Many early films were made near the major New York performing market, so Rogers could make the film, yet still rehearse and perform in the Follies. He eventually appeared in most of the Follies from 1916 to 1925.

Movies

Rogers and his young family moved permanently to the West Coast in 1919, when Goldwyn Pictures moved to join the rise of

filmmaking in California.[13] During the same period of time Rogers made 12 silent movies for Goldwyn, until his contract ended in 1921, he was also

making the Illiterate Digest film-strip series for the Gaumont Film Company.

While Rogers enjoyed film acting, his appearances in silent movies suffered from the obvious restrictions of silence—not the strongest medium for him, having gained his fame as a commentator on stage. It helped somewhat that he wrote a good many of the title cards appearing in his films. In 1923, he began a one-year stint for Hal Roach and made 12 pictures. Among the films he made for Roach in 1924 were three directed by Rob Wagner: Two Wagons Both Covered, Going to Congress and Our Congressman. He made two other feature silents and a travelogue series in 1927, and did not return to the screen until his time in the 'talkies' began in 1929.

From 1929 to 1935, Rogers became the star of the Fox Film lot (now 20th Century Fox). Far from being a "B-Movie" level performer, Rogers appeared in

21 feature films alongside such noted performers as Lew

Ayres, Billie Burke, Richard Cromwell,

Jane Darwell, Andy Devine, Janet Gaynor, Rochelle Hudson, Boris Karloff, Myrna Loy, Joel McCrea, Hattie McDaniel, Ray Milland, Maureen O'Sullivan, ZaSu Pitts, Dick Powell, Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, Mickey Rooney, and Peggy Wood. He was directed three times by John Ford. He appeared in three films with his friend Stepin Fetchit (aka Lincoln T. Perry), David Harum (1934), Judge Priest (1934) and The County Chairman (1935).[14]

With his voice becoming increasingly familiar to audiences, he was able to basically play himself, without normal makeup, in each

film, managing to ad-lib and even work in his familiar commentaries on politics at times. The clean moral tone of his films led to various public schools taking their classes, during the school

day, to attend special showings of some of them. His most unusual role may have been in the first talking version of Mark Twain's novel A Connecticut Yankee

in King Arthur's Court. His popularity soared to new heights with films including Young As You Feel, Judge Priest, and Life Begins at 40 with Richard Cromwell and

Rochelle Hudson.

[edit] Travel

Rogers began a weekly column, titled "Slipping the Lariat Over," at the end of 1922.[15] He had already published a book of wisecracks and had begun a steady stream of humor books.[5] Through the continuing series of columns for the McNaught Syndicate between 1922 and 1935, as well as in his personal appearances and radio broadcasts, he won the loving admiration of the American people, poking jibes in witty ways at the issues of the day and prominent people—often politicians. He wrote from a non-partisan point of view and became a friend of presidents and a confidant of the great. Loved for his cool mind and warm heart, he was often considered the successor to such greats as Artemus Ward and Mark Twain. Rogers was not the first entertainer to use political humor before his audience. Others such as Broadway comedian Raymond Hitchcock and Britain's Sir Harry Lauder precede him by several years. The legendary Bob Hope is the best known political humorist to follow Rogers's example.

From 1925 to 1928, Rogers traveled the length and breadth of the United States in a "lecture tour". (He began his lectures by pointing out that "A humorist entertains, and a lecturer annoys!") During this time he became the first civilian to fly from coast to coast with pilots flying the mail in early air mail flights. The National Press Club dubbed him "Ambassador at Large of the United States." He visited Mexico City with Charles Lindbergh as a guest of U.S. Ambassador Dwight Morrow, whose daughter Anne later married Lindbergh. In subsequent years, Rogers gave numerous after-dinner speeches, became a popular convention speaker, and gave dozens of benefits for victims of floods, droughts, or earthquakes. In 1928 he ran for President of the United States.[16] From 1930 to 1935, he made radio broadcasts for the Gulf Oil Company. This weekly Sunday evening show, The Gulf Headliners, ranked among the top radio programs in the country.[17] Since he easily rambled from one subject to another, reacting to his studio audience, he often lost track of the half-hour time limit in his earliest broadcasts, and was cut off in mid-sentence. To correct this, he brought in a wind-up alarm clock, and its on-air buzzing alerted him to begin wrapping up his comments. By 1935, his show was being announced as "Will Rogers and his famous Alarm Clock."

He made a trip to the Orient in 1931 and to Central and South America the following year. In 1934, he made a globe-girdling tour and returned to play the lead in Eugene O'Neill's stage play Ah, Wilderness! He had tentatively agreed to go on loan from Fox to MGM to star in the 1935 movie version of the play; however, his concern over a fan's reaction to the 'facts-of-life' talk between his character and its son caused him to decline the role—and that freed his schedule to allow him to fly with Wiley Post that summer.

In 1934, Rogers hosted the 6th Annual Academy Awards Ceremony, held at the Fiesta Room of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. At the same time, he also began writing a popular syndicated short item called "Will Rogers Says". Literally a telegram which he composed daily to address each day's news, it often appeared on the front pages of its subscribing papers. He identified with the Democratic Party, saying "I'm not a member of any organized party. I'm a Democrat," and was a vocal supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt. At one point, he was even asked to run for governor of Oklahoma, the party hoping to benefit from his immense popularity.

"I never yet met a man that I didn't like"

One of Will Rogers's most famous lines, "I have never yet met a man that I dident [sic] like," was part of a longer quotation and it originally referred to Leon Trotsky:

| “ |

I bet you if I had met him and had a chat with him, I would have found him a very interesting and human fellow, for I

never yet met a man that I dident [sic] like. When you meet people, no matter what opinion you might have formed about them beforehand, why, after you meet them and see their angle

and their personality, why, you can see a lot of good in all of them.[18]

Saturday Evening Post, November 6, 1926

|

” |

Quotes

- Our foreign policy is an open book - a checkbook

- I belong to no organized party, I'm a Democrat

- Lettin' the cat out of the bag is a lot easier than puttin' it back in

- People who fly into a rage always make a bad landing

-

The income tax has made more liars out of Americans than golf[19]

- If stupidity got us in this mess, why can't it get us out?

-

Death and legacy

In 1935 Post became interested in surveying a mail-and-passenger air route from the West Coast of the United States to Russia.

Short on cash, he built a plane using parts salvaged from two different aircraft: the fuselage of an airworthy Lockheed Orion and the wing of a wrecked experimental Lockheed Explorer. The

Explorer wing was six feet longer in span than the Orion's original wing, an advantage which extended the range of the hybrid aircraft. As the Explorer wing did not have retractable landing gear,

it also lent itself to the fitting of floats for landing in the lakes of Alaska and Siberia. Post's friend Will Rogers visited him often at the airport in Burbank, California while he was

modifying the aircraft, and asked Post to fly him through Alaska in search of new material for his newspaper column. When the floats Post had ordered did not arrive at Seattle in time, he used a

set that was designed for a larger type, making the already nose-heavy hybrid aircraft still more nose-heavy.[20] According to the research of Bryan Sterling, the

floats were the correct type.[21]

After making a test flight in July, Post and Rogers left Seattle in the Vega in early August and then made several stops in Alaska. While Post piloted the aircraft, Rogers wrote his columns on his typewriter. Before they left Fairbanks they signed and mailed a yacht club burgee belonging to South Coast Corinthian Yacht Club. The signed Burgee is on display at South Coast Corinthian Yacht Club in Marina del Rey, California. On August 15, they left Fairbanks, Alaska for Point Barrow. They were a few miles from Point Barrow when they became uncertain of their position in bad weather and landed in a lagoon to ask directions. On takeoff, the engine failed at low altitude, and the aircraft, uncontrollably nose-heavy at low speed, plunged into the lagoon, shearing off the right wing and ended inverted in the shallow water of the lagoon. Both men died instantly.

Oklahoma honors

One of Oklahoma's two statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection, housed in

the United States

Capitol, is of Rogers. The work was paid for by a state appropriation and was sculpted in clay by Jo Davidson, a close friend of Rogers whom he nicknamed the "headhunter" because Davidson was always looking for heads to sculpt, then

cast in bronze in Brussels, Belgium. Dedicated on June 6, 1939 before a crowd of more than 2,000 people,

the statue faces the floor entrance of the House of Representatives Chamber next to National Statuary Hall. The Architect of the Capitol, David

Lynn, said there had never been such a large ceremony or crowd in the Capitol.[1]

Oklahoma leaders asked Rogers to represent the state as one of their two statues in the Capitol, and Rogers agreed on the

condition that his image would be placed facing the House Chamber, supposedly so he could "keep an eye on Congress." Of the statues in this part of the Capitol, the Rogers sculpture is the only

one facing the Chamber entrance. According to guides at the Capitol, each President rubs the left shoe of the Rogers statue for good luck before entering the House Chamber to give the State of the Union Address.[22]

Oklahoma has named many places and buildings for Rogers. His birthplace is located two miles east of Oologah, Oklahoma. The house itself was moved about ¾ mile (1.2 km) to its present location overlooking its original site when the Verdigris River valley was flooded to create Oologah Lake. The family tomb is at the Will Rogers Memorial Museum in nearby Claremore, which stands on the site purchased by Rogers in 1911 for his retirement home. In 1944, Rogers's body was moved from a holding vault in California to the tomb; his wife Betty was interred beside him later that year upon her death. A casting of the Davidson sculpture that stands in National Statuary Hall, paid for by Davidson personally, resides at the museum. Both the birthplace and the museum are open to the public.

Will Rogers World Airport in Oklahoma City was named for him, as was the Will Rogers Turnpike, also known as the section of Interstate 44 between Tulsa and Joplin, Missouri. Near Vinita, Oklahoma, a statue of Rogers stands outside the west anchor of the McDonald's that spans both lanes of the interstate. A recent expansion and renovation of the Will Rogers World Airport includes a statue of Will Rogers on horseback in front of the terminal.

There are 13 public schools in Oklahoma named Will Rogers, including Will Rogers High School in Tulsa. The University of Oklahoma named the large Will Rogers Room in the student union for him,[23] as did the Boy Scouts of America with the Will Rogers Council and the Will Rogers Scout Reservation near Cleveland.

California memorials

Rogers's home, stables, and polo fields are preserved today for public enjoyment as Will Rogers State Historic Park in Pacific Palisades. His widow, Betty, willed the property to the state of California upon her death in 1944 under the condition that polo be played on the field every year[24]. Will Rogers Elementary School in Santa Monica is named for Rogers. There are two Middle Schools named Will Rogers (one in Long Beach and the other in Fair Oaks). A United States Navy submarine USS Will Rogers is also named in his honor. A small park on Sunset Boulevard and Beverly Drive in Beverly Hills was named Will Rogers Memorial Park after him. Also, a beach in Malibu was named Will Rogers Beach.

U.S. Route 66 is known as the Will Rogers Highway; a plaque dedicating the highway to the humorist is located opposite the western terminus of Route 66 in Santa Monica.

Texas memorials

The Will Rogers Memorial Center was built in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1936. A mural of Rogers on his horse, Soapsuds, hangs in the lobby of the coliseum, and a bust of Rogers sits in the rotunda of the Landmark Pioneer Tower. A life-size statue of Rogers on Soapsuds, titled Into the Sunset and sculpted by Electra Waggoner Biggs, resides on the lawn.

A casting of Into the Sunset stands in the entrance to the main campus quad at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas. This memorial was dedicated on February 16, 1950, by Rogers longtime friend Amon G. Carter. Carter believed Texas Tech was the perfect setting for the statue and that it would fit into the traditions and scenery of West Texas.

The statue stands at 9 feet 11 inches tall and weighs 3,200 pounds; its estimated cost was $25,000. On the base of the statue, the inscription reads "Lovable Old Will Rogers on his favorite horse, 'Soapsuds,' riding into the Western sunset."

Today, Texas Tech tradition and legend surround the statue. According to one legend, the plan to face Will Rogers so that he could be riding off into the sunset did not work out as it would cause Soapsuds' rear to be facing visitors entering campus from downtown. To solve this problem, the horse and Will were turned 23 degrees to the east so the horse's posterior was facing in the direction of Texas A&M, one of the school's rivals.

Before every home football game the Saddle Tramps wrap Old Will with red crepe paper. Will Rogers and Soapsuds have also been wrapped in black crepe paper to mourn national tragedies.

A third casting resides at the Will Rogers Memorial in Claremore, Oklahoma.

National tributes

Rogers's eldest son, Bill, starred as his father in the 1952 biopic The Story of Will Rogers. Rogers also came to life for modern audiences in the Tony Award-winning musical The Will Rogers Follies, with Keith Carradine in the lead role, and he was also portrayed by James Whitmore in the one-man show Will Rogers' U.S.A.

Colorado Springs philanthropist Spencer Penrose named a monument on Cheyenne Mountain the Will Rogers Shrine of the Sun [1]in honor of his good friend.

On November 4, 1948, the United States Post Office commemorated Rogers with a first day cover of a 3-cent stamp with his image—the inscription reads, "In honor of Will Rogers, Humorist, Claremore, Oklahoma." He was also later honored on the centennial of his birth, in 1979, with the issue of a United States Postal Service 15-cent stamp as part of the "Performing Arts" series.

The Barrow, Alaska airport (BRW), located about 16 miles (26 km) from the location of their fatal airplane crash, is known as the Wiley Post-Will Rogers Memorial Airport.

Film portrayals

Rogers was portrayed by A.A. Trimble in cameos in both the 1936 film, The Great Ziegfeld,[25] and the 1937 film, You're a Sweetheart.[26]

Rogers was portrayed by his son, Will Rogers, Jr., in a cameo in the 1949 film, Look for the Silver Lining,[27] and as the star of

the 1952 film, The Story of Will Rogers.[28]

Rogers was portrayed by actor Keith Carradine in the 1994 film Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle.[29] Carradine had previously played Rogers three years earlier on Broadway, in the stage musical, The Will Rogers Follies.

Filmography

Silent films

|

|

Travelog Series

|

Sound films

|

|

|

Bibliography

- Johnson, Bobby H. and R. Stanley Mohler. "Wiley Post, His Winnie Mae, and the World's First Pressure Suit." Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1971.

- Rogers, Will (1975) [1924]. Joseph A. Stout, Jr.. ed. Rogers-isms: The Cowboy Philosopher On Prohibition. Stillwater: Oklahoma State University Press. ISBN 091495606X.

- Rogers, Will (March 2003) [1924]. Illiterate Digest. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0766143210.

- Rogers, Will (1977) [1926]. Joseph A. Stout. ed. Letters Of A Self-Made Diplomat To His President. Stillwater: Oklahoma State University Press. ISBN 0914956094.

- Rogers, Will (December 1982). Steven K. Gragert. ed. More letters of a self-made diplomat. Stillwater: Oklahoma State University Press. ISBN 9780914956228.

- Rogers, Will (1927). There's Not A Bathing Suit In Russia.

- Rogers, Will (1982) [1928]. "He chews to run": Will Rogers's Life magazine articles, 1928. Stillwater: Oklahoma State University Press. ISBN 0914956205.

- Rogers, Will (1983). Steven K. Gragert. ed. Radio Broadcasts of Will Rogers. Stillwater: Oklahoma State University Press. ISBN 0914956248.

- Sterling, Bryan and Frances (2001). Forgotten Eagle: Wiley Post: America's Heroic Aviation Pioneer. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 0-78670-894-8.

-

The Papers of Will Rogers

- Rogers, Will (February 1996). Steven K. Gragert and M. Jane Johansson. ed. The Papers of Will Rogers: The Early Years : November 1879-April 1904. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806127453.

- Rogers, Will (September 2000). Steven K. Gragert and M. Jane Johansson, eds.. ed. Papers of Will Rogers : Wild West and Vaudeville, April 1904-September 1908, Volume Two. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806132679.

- Rogers, Will (2005-09-28). Steven K. Gragert and M. Jane Johansson. ed. The Papers of Will Rogers: From Broadway to the National Stage, September 1915 – July 1928. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806137049.

- Rogers, Will (2005-09-28). Steven K. Gragert and M. Jane Johansson. ed. The Papers of Will Rogers: From Broadway to the National Stage, September 1915 – July 1928. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806137049.

- Rogers, Will (2006-10-31). Steven K. Gragert and M. Jane Johansson. ed. The Papers of Will Rogers: The Final Years, August 1928 – August 1935. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806137681.

See also

-

Will Rogers phenomenon

-

Will Rogers Shrine of the Sun

-

Will Rogers Memorial

- List of people on the cover of Time Magazine: 1920s - 19 July 1926

-

The Will Rogers Follies

-

Notes

- ^ a b Curtis, Gene (2007-06-05). "Only in Oklahoma: Rogers statue unveiling filled U.S. Capitol". Tulsa World. http://www.tulsaworld.com/webextra/itemsofinterest/centennial/centennial_storypage.asp?ID=070605_1_A4_cpRog15817. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- ^ a b c Rogers State University (2007-04-18). "RSU and Will Rogers Museum to Discuss Possible Merger". Press release. http://web.archive.org/web/20071107065122/http://www.rsu.edu/news/2007/04-18_willrogersmuseum.html. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ^ a b c Schlachtenhaufen, Mark (2007-05-31). "Will Rogers grandson carries on tradition of family service". OkInsider.com. Oklahoma Publishing Company. http://web.archive.org/web/20070928161652/http://www.okinsider.com/topic_01OF0MMAHY/readstory.oki?storyid=03K101DDQ. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- ^ Yagoda, p. 8

- ^ a b c d "Adventure Marked Life of Humorist". The New York Times. 1935-08-17. http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/1104.html. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ^ Carter, Joseph H. and Larry Gatlin. The Quotable Will Rogers." Layton, Utah: Gibbs Smith, Publisher, 2005:20.

- ^ Ferguson, Deborah (2003-01-10). "Ferguson's Family Tree & Branches". RootsWeb. http://worldconnect.rootsweb.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=GET&db=debbieferguson&id=I17856. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ^ "Origin of County Names in Oklahoma." Oklahoma History Society's Chronicles of Oklahoma. 2:1, March 1924 (retrieved 18 Jan 09)

- ^ a b c "Chewing Gum and Rope in the Temple". The New York Times: p. 90. 1915-10-03.

- ^ Yagoda, p. 56

- ^ "Give A Thought To Will". The New York Times: p. 13. 1922-11-13.

- ^ Vanity Fair magazine September 1921, accessed 2009

- ^ "Written On The Screen". The New York Times: p. 50. 1919-06-08.

- ^ Lamparski, Richard (1982). Whatever Became Of ...? Eighth Series. New York: Crown Publishers. pp. 106–7. ISBN 0-517-54855-0.

- ^ Rogers, Will (1922-12-31). "Slipping the Lariat Over (December 31, 1922)". The New York Times.

- ^ Beam, Christopher; Chadwick Matlin (2007-10-23). "Will Rogers: The Stephen Colbert of his time.". Slate. http://www.slate.com/id/2176386/#rogers.

- ^ "Will Rogers: Radio Pundit". Will Rogers Memorial Museums <http://www.willrogers.com>. 2008-03-31. http://www.willrogers.com/willrogers/radio/rp.html.

- ^ Yagoda, p. 234

-

^ "Will Rogers Quotes."

- ^ Johnson, Bobby H. and R. Stanley Mohler, "Wiley Post, His Winnie Mae, and the World's First Pressure Suit.", Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1971.

- ^ Sterling, Bryan and Frances (2001). Forgotten Eagle: Wiley Post: America's Heroic Aviation Pioneer. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 0-78670-894-8.

- ^ "Police Dept., police explorers strolls through the streets of the U.S. Capitol, stops for visits". The Anderson Independent-Mail. 2007-07-18. http://www.independent-mail.com/news/2007/jul/18/police-dept-police-explorers-strolls-through-stree/. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ^ "Oklahoma Memorial Union - Will Rogers Room". Union.ou.edu. http://union.ou.edu/content/view/20/7/. Retrieved 2009-08-14.

-

^ Will Rogers Polo Club http://www.willrogerspolo.org/polo.html

-

^ Internet Movie Database entry for The Great Ziegfeld

-

^ Internet Movie Database entry for You're a Sweetheart

-

^ Internet Movie Database entry for Look for the Silver Lining

-

^ Internet Movie Database entry for The Story of Will Rogers

-

^ Internet Movie Database entry for Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle

-

References

- O'Brien, P. J. (1935). Will Rogers: Ambassador of Good Will, Prince of Wit and Wisdom. N.P.: Winston.

- Yagoda, Ben (April 2000). Will Rogers: A Biography. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806132389.

External links

|

|

Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Will

Rogers |

|

|

Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Will

Rogers |

-

Will Rogers at the Internet Movie Database

-

The Official Site of Will Rogers

-

Will Rogers Birthplace

-

Will Rogers Museums

-

Will Rogers State Historic Park

-

Will Rogers Polo Club

-

Will Rogers World Airport

-

Will Rogers in 3 excerpts

from 1935 broadcasts

-

Will Rogers Institute

-

The Tulsa World's Will Rogers site

-

Will Rogers at the Internet Broadway Database

-

Will Rogers at Find a Grave

|

[hide]

|

|

|---|---|

|

Douglas Fairbanks / William C. deMille (1929) · William C. deMille (1930) · Conrad Nagel (1930) · Lawrence Grant (1931) · Lionel Barrymore / Conrad Nagel (1932) · Will Rogers (1934) · Irvin S. Cobb (1935) · Frank Capra (1936) · George Jessel (1937) · Bob Burns (1938) · None (1939) · Bob Hope (1940) |

|

Meher Baba's Life & Travels

Meher Baba's Life & Travels