Born :

Died :

ENGLISH - AMERICAN

A Theosophist

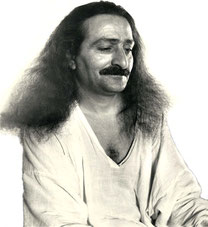

Meher Baba traveled from Port Said to Venice on the ship Conte Rosso in April 1932. On board he met with Professor Ernest Wood. Wood was a Theosophical teacher who worked at the Theosophical headquarters in Madras, India.

Baba explained to Wood at length what he meant by spirituality. Wood wrote a number of books on Theosophy, including 'Is This

Theosophy?'

(1936)

(LM5 p1548)

Professor Ernest Egerton Wood (* 18 August 1883 in Manchester, England; + 17 September 1965 in Houston, United States) was a noted yogi, theosophist, Sanskrit scholar, and author of numerous books, including Concentration - An Approach to Meditation and Yoga.

Contents |

Youth and Education

Wood was educated at the Manchester College of Technology, where he studied chemistry, physics and geology. Because of his interest in Buddhism and Yoga, he began to learn the Sanskrit language.

Theosophy

As a young man, Wood became interested in Theosophy after listening to lectures by the theosophist Annie Besant, whose personality impressed him greatly. He joined the society's Manchester lodge and in 1908 followed Besant, who had become President of the Theosophical Society Adyar, to India. Wood became one of her assistants, working with Besant and Charles Webster Leadbeater, who had arrived in Adyar in 1909.

Wood observed the discovery of the boy Jiddu Krishnamurti by Leadbeater, who soon declared Krishnamurti to be the

vehicle for the "coming World Teacher". Wood's account of this discovery is in his autobiography, Is this Theosophy...?, published in 1936, and in two articles written after

that.

At Besant's suggestion, Wood became involved in education, and after 1910, he served as headmaster of several schools and colleges founded by the Theosophical Society. Wood became Professor of Physics, Principal and President of the Sind National College and the Madanapalle College, both teaching colleges of the Bombay and Madras Universities. Wood promoted theosophical ideas, conducting lecturing tours and publishing numerous articles, essays and books on a variety of theosophical subjects, among them a digest of Helena P. Blavatsky's Secret Doctrine. His lectured throughout India and travelled to many countries in Asia, Europe, and the Americas. He continued to reside in India until the close of World War II, when he relocated to the United States.

Wood become disillusioned about the future of the Theosophical Society and began to study the yoga classics. Following the Krishnamurti affair, which caused a splitting of the society, Wood

campaigned for election to the office of president after Annie Besant's death in 1933. He was defeated by George Arundale, one of Charles Leadbeater's close allies, in a campaign that Wood

later described as unfair and questionable. Disenchanted with the society's direction, but impressed with the now mature and independent Krishnamurti, Wood turned to Yoga.

Yoga

In India, Wood had encountered many yogis and Hindu pundits. As a practising yogi, vegetarian and teetotaller, having adopted this lifestyle after reading Sir Edwin Arnold's The Light of Asia in his boyhood, he was warmly received by Indian yogis, many of whom became Wood's friends and advisers.

During his early years in Adyar, the Head of the Vedantic Monastery Shri Shringeri Shivaganga Samasthanam in Mysore Province, Sri Jagat Guru Shankara Charya Swami, bestowed upon Wood the title of "Shri

Sattwikagraganya" in recognition of his efforts to introduce Indian pupils to Sanskrit.

Wood did not officially become a student of any Indian master. However, during a visit to New York in 1928, he again met with Krishnamurti, who was leaving the Theosophical Society to

become an independent teacher, renouncing the ceremonies and occult hierarchies created by the leadership of the Society. This meeting affected Wood deeply, and he returned to the classic yoga

literature as a source of inspiration. Wood spent his remaining years writing and publishing on yoga. He moved to the United States, where he served for a short time as president and dean of the

American Academy of Asian Studies in San Francisco, and later moved to Houston, Texas, working for the University of Houston, Texas. Together with his wife,

Hilda, Wood helped in the establishment of the School of the Woods, a Montessori school in Houston, Texas, which was named after them.

Shortly after his arrival in India, Wood had begun translating the Indian classics, such as the Garuda Purana. In the late 1920s, he began a thorough study of the Yoga classics with the assistance of several Hindu scholars, leading to the publication of numerous translations of famous yoga texts such as the Bhagavad Gita, Patañjali's Yoga Sutras, Shankara's Viveka Chudamani. In his commentaries to these translations, Wood tried to make these texts' philosophical ideas applicable to modern life. His writings contain many references to his own practical experiences in these matters. Together with his concise treatises of yoga, such as the volume Yoga, Penguin Books,1959/62, and his earlier writings on concentration and memory training, Wood's works contain a complete introduction to the classic texts of Raja Yoga, or the yoga of the mind, with a sparing use of Sanskrit expressions.

Wood died on September 17, 1965, days after finishing his translation of Shankara's Viveka Chudamani, which was posthumously

published and entitled The pinnacle of Indian thought.

References

-

^ Ernest Wood: "Clairvoyant investigations by C.W. Leadbeater on Alcyone's (or Krishnamurti's) previous lives." (with extensive notes by C.

Jinarajadasa)

-

^ Ernest Wood: "There is no religion higher than truth", on the discovery of Jiddu Krishnamurti, his youth and upbringing and Leadbeater's role

in this

-

^ a b

c Wood, Ernest E. (1936). "Is this

Theosophy...?", Rider & Co.

- ^ Homepage of the School of the Woods, history section (retrieved 24 Oct. 2006)

- ^ Wood, Ernest E. (1967), "The Pinnacle of Indian Thought", editor's note by Hilda Wood, p.161.

-

Partial List of Works

- The Garuda Purana (Saroddhara). The Sacred Books of the Hindus, Vol. 9. Indian Press 1911.

- The Seven Rays. 1925.

-

The Intuition of the Will. The Theosophical Press 1927. ISBN 0-7661-9095-1

- An Englishman Defends Mother India. A Complete Constructive Reply to „Mother India“, Ganesh & Co. 1929, revised 1930.

- The Occult Training of the Hindus, 1931 (republished in 1976 under the title Seven Schools of Yoga by the Theosophical Publishing House).

- The Song of Praise to the Dancing Shiva. Ganesh & Co. 1931.

- Mind and Memory Training. Theosophical Publishing House 1936.

-

Is this Theosophy...? (Autobiography) Rider & Co. 1936. ISBN 0-7661-0829-5

- Practical Yoga, Ancient and Modern, with an Introduction by Paul Brunton. E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc. 1948.

-

Concentration - An Approach to Meditation. Theosophical Publishing House 1949. ISBN

0-8356-0176-5

- Practical Yoga, Ancient and Modern, Being a New, Independent Translation of Patanjali's Yoga Aphorisms, Interpreted in the Light of Ancient and Modern Psychological Knowledge and Practical Experience. Rider and Company 1951.

- The Glorius Presence, A Study of the Vedanta Philosophy and Its Relation to Modern Thought, Including a New Translation of Shankara's Ode to the South-Facing Form. Rider & Co. 1952.

- Great Systems of Yoga. Philosophical Library 1954.

- The Bhagavad Gita Explained, With a New and Literal Translation. New Century Foundation Press 1954.

- Yoga Dictionary. Philosophical Library 1956.

-

Zen Dictionary. Philosophical Library 1957. ISBN 0-14-021998-6

- Yoga. Penguin Books 1959. Revised 1962.

- A Study of Pleasure and Pain. The Theosophical Press 1962.

- Vedanta Dictionary. Philosophical Library 1964.

- The Pinnacle of Indian Thought, Being a new, independent translation of the Viveka Chudamani (Crest Jewel of Discrimination) with commentaries. The Theosophical Publishing House, 1967.

- Come Unto Me and Other Writings. The Theosophical Publishing House 2000.

-

External links

- Ernest Wood: "Clairvoyant investigations by C.W. Leadbeater on Alcyone's (or Krishnamurti's) previous lives". (with extensive notes by C. Jinarajadasa)

Ernest Wood

Ernest Egerton Wood was born in England in 1883 and joined

the Theosophical Society in 1902. He lectured for the Society for a period of 30 years in 40 countries. He came to Adyar, the international Headquarters of the TS, in 1908 and assisted Annie

Besant in educational work, scouting and other areas. He was the founder of the Theosophical College in Madanapalle, which is also the birth place of J. Krishnamurti. He was also the founder and

once the Principal of the Sind National College in Hyderabad. He served for several years as secretary to C. W. Leadbeater at Adyar. He married Hilda Wood in 1916. He served as Recording

Secretary of the TS from 1929 to 1933, and was a candidate for the Presidency of the Society in the 1934 election.

Ernest Egerton Wood was born in England in 1883 and joined

the Theosophical Society in 1902. He lectured for the Society for a period of 30 years in 40 countries. He came to Adyar, the international Headquarters of the TS, in 1908 and assisted Annie

Besant in educational work, scouting and other areas. He was the founder of the Theosophical College in Madanapalle, which is also the birth place of J. Krishnamurti. He was also the founder and

once the Principal of the Sind National College in Hyderabad. He served for several years as secretary to C. W. Leadbeater at Adyar. He married Hilda Wood in 1916. He served as Recording

Secretary of the TS from 1929 to 1933, and was a candidate for the Presidency of the Society in the 1934 election.

Prof. Wood was the author of many books, which include A Guide to Theosophy; Reincarnation; Concentration: An Approach to Meditation; Memory Training; Character Building; Destiny; Intuition

of the Will; The Seven Rays; Raja Yoga; The Pinnacle of Indian Thought; The Glorious Presence: The Vedanta Philosophy Including Shankara's Ode To The South-Facing Form; Practical Yoga, Ancient

And Modern; Seven Schools Of Yoga; An Englishman Defends Mother India; Natural Theosophy, among others. He was awarded the T. Subba Row Medal in 1924 for his contribution to theosophical

literature. He also received the title of Sattwikagraganya awarded by the Head of the Mysore monastery in India. He passed away in 1965.

(Source: The Theosophical Year Book 1937)

(From Ernest Wood’s book Is This Theosophy…?)

It is doubtful whether any clairvoyant operates through senses in

any way comparable with those familiar to us as sight, hearing and the rest. It is more than probable that when impressions are clearly received in terms of these (as when I heard the sentence

relating to the five of clubs) it is due to “visualization” superimposed upon the impression, and forming a species of interpretation. When I put this theory before Mr. Leadbeater he quite agreed

to it and wrote a passage to that effect in one of his books.

My own position with regard to Mr. Leadbeater, therefore, was midway between the extremes of acceptance and rejection. It was that

of one who had otherwise had convincing proof of the existence of clairvoyant power (though not on anything like the lavish scale presented by Mr. Leadbeater, nor of the perfect accuracy which he

always took for granted in his own case), who did not see any reason why Mr. Leadbeater should cheat, but many reasons why he should not do so, who, knowing him and liking him, was prepared to

give him the benefit of the doubt where at all reasonable, who at the same time knew that human nature was streaky (like bacon, as it has been said) and did not expect Mr. Leadbeater to be

perfect in all respects, even though the devotees thought him to be so.

I found, on the other hand, that most of my friends were rather in the position expressed in an article which I read recently, in

which the writer said: “I accept that as true, being ignorant of the matter.” Some few were actually a little afraid of disbelief. They might miss something good, or even “something” might happen

to them. I was reminded of the story of the old lady who bowed whenever the devil was mentioned, and when asked why she did so, replied: “Well, minister, it’s best to be ready for

everything.”

There had been charges against Mr. Leadbeater of very reprehensible actions with boys, but Mrs. Besant had been satisfied that

they were unsound, and had readmitted him to her closest friendship. I am convinced to this day that he loved young people and would do nothing intentionally to harm them, and during the whole of

my close contact with him, intermittently covering thirteen years, I never saw in him any signs of sexual excitement or desire. Only once or twice we talked of the attacks made upon him. He said

that evidence had been manufactured against him. He had given advice, in good faith, and with the best intentions, which Mrs. Besant had disapproved. In deference to her wishes, he had promised

not to give that advice again, although his opinion still was that it was the best under the circumstances. (p.

142-143)

Ernest Wood wrote in " The American Theosophist 1933-1996 " by Weaton, an article in January 1934 called " If I were President ".

http://appshopper.com/reference/ernest-woods-great-systems-of-yoga

Great Systems of Yoga

by Ernest Wood

This is a short review of the major schools of yoga, including Hindu, Buddhist and Sufi varieties. Wood, whose translation of the

The Garuda Purana is also at this site, was a founding Theosophist and wrote extensively on Hinduism, and Yoga in particular. His works on the subject are written for Western readers, and where

he needs to use Sanskrit or other esoteric terms, he takes care to explain them. He was a practicing Yogi for most of his lifetime.

Contents:

The Ten Oriental Yogas;

Patanjali's Raja Yoga;

Shri Krishna's Gita Yoga;

Shankaracharya's Gnyana Yoga;

The Hatha and Laya Yogas;

The Bhakti and Mantra Yogas.

About the Author:

"Professor Ernest Egerton Wood (18 August 1883 in Manchester, England; - 17 September 1965 in Houston, United States) was a noted

yogi, theosophist and author of numerous books, including Concentration - An Approach to Meditation and Yoga.

He was also a Sanskrit scholar. Wood received his education at the Manchester College of Technology, where he studied chemistry,

physics and geology. Because of an early interest in Buddhism and Yoga, he also started to learn the Sanskrit language. As a young man, Wood became interested in Theosophy after listening to

lectures by the theosophist Annie Besant, whose personality impressed him greatly.

He consequently joined the society's Manchester lodge, then one of the world's largest, and in 1908 followed Annie Besant to India

after she had become President of the Theosophical Society Adyar. Wood soon became one of her assistants, working in close contact with both Annie Besant and Charles Webster Leadbeater, who had

arrived in Adyar in 1909. Due to his close working relationship with Leadbeater, Wood was in a position to observe the discovery of the boy Jiddu Krishnamurti by Leadbeater, who soon declared him

to be the vehicle for the "coming World Teacher". Wood's own eyewitness account of the events surrounding this discovery is detailed in his autobiography, Is this Theosophy...?, published in

1936, and in two articles written after that. At the suggestion of Annie Besant, Wood became deeply engaged in educational work. Since 1910, he served as headmaster of several schools and

colleges founded by the Theosophical Society. He became Professor of Physics, Principal and President of the Sind National College and the Madanapalle College, both teaching colleges of the

Bombay and Madras Universities.

He actively promoted theosophical ideas by conducting lecturing tours and publishing numerous articles, essays and books on a

variety of theosophical subjects, among them a Digest of Helena P. Blavatsky's Secret Doctrine. His lecturing led him to places all over India, and he also traveled to many countries in Asia,

Europe, and the Americas. India stayed his place of residence until the close of World War II, when he relocated to the United States. It was only after becoming disillusioned about the future of

the Theosophical Society that Wood started to devote himself primarily to a thorough study of the yoga ..." (Quote from

sacred-texts.com)

http://www.scribd.com/doc/4004431/Ernest-Wood-Concentration

The author, Professor Ernest Wood, was born in England and educated in the field of science. As a young man he went to India where he spent many years as an educationist, serving as principal of various schools, colleges and universities, and also as a worker for the world-wide Theosophical Society. Professor Wood became deeply interested in the Yoga and Vedanta philos- ophies of India and has written many books on these subjects, as well as on education and psychology. After leaving India he was for some time President and Dean of the American Academy of Asian Studies, a graduate school in San Francisco.

Biography

Youth and Education

Wood received his education at the Manchester College of Technology, where he studied chemistry, physics and geology. Because of an early interest in Buddhism and Yoga, he also started to learn the Sanskrit language.

Theosophy

As a young man, Wood became interested in Theosophy after listening to lectures by the theosophist Annie Besant, whose personality impressed him greatly. He consequently joined the society's Manchester lodge, then one of the world's largest, and in 1908 followed Annie Besant to India after she had become President of the Theosophical Society Adyar. Wood soon became one of her assistants, working in close contact with both Annie Besant and Charles Webster Leadbeater, who had arrived in Adyar in 1909.

Due to his close working relationship with Leadbeater, Wood was in a position to observe the discovery of the boy Jiddu Krishnamurti by Leadbeater, who soon declared him to be the vehicle for the "coming World Teacher". Wood's own eyewitness account of the events surrounding this discovery is detailed in his autobiography, Is this Theosophy...?, published in 1936, and in two articles written after that.

At the suggestion of Annie Besant, Wood became deeply engaged in educational work. Since 1910, he served as headmaster of several schools and colleges founded by the Theosophical Society. He became Professor of Physics, Principal and President of the Sind National College and the Madanapalle College, both teaching colleges of the Bombay and Madras Universities. He actively promoted theosophical ideas by conducting lecturing tours and publishing numerous articles, essays and books on a variety of theosophical subjects, among them a Digest of Helena P. Blavatsky's Secret Doctrine. His lecturing led him to places throughout India, and he also traveled to many countries in Asia, Europe, and the Americas. India stayed his place of residence until the close of World War II, when he relocated to the United States.

It was only after becoming disillusioned about the future of the Theosophical Society that Wood started to devote himself primarily to a thorough study of the yoga classics. In the wake of the Krishnamurti affair, which had led to the splitting of the society, Wood decided to campaign for the office of president after Annie Besant's death in 1933. He was however defeated by George Arundale, one of Charles Leadbeater's close allies, in a campaign that Wood later described as unfair and questionable. Disenchanted about the direction the society had taken, but very impressed with the now mature and independent Krishnamurti, Wood turned to yoga.

Yoga

In India Wood had come into close contact with many yogis and Hindu pundits. As a practising yogi, vegetarian and teetotaller (he had adopted this lifestyle after reading Sir Edwin Arnold's The Light of Asia in his boyhood) he was warmly received by Indian yogis, many of whom became friends and advisers to him. During his early years in Adyar, the Head of the Vedantic Monastery Shri Shringeri Shivaganga Samasthanam in Mysore Province, Sri Jagat Guru Shankara Charya Swami, bestowed upon Wood the title of "Shri Sattwikagraganya" in recognition of his efforts to introduce Indian pupils to Sanskrit.

Wood did, however, apparently not become an official pupil to any Indian master, the way several other Westerners did. In 1928, during a visit to New York, he again came into contact with Krishnamurti, who was by then turning away from the Theosophical Society, gradually to become a teacher in his own right, renouncing the ceremonies and occult hierarchies created by the leadership of the Society. Wood describes in his autobiography how deeply this meeting affected him, prompting him to turn back to the classic yoga literature as a source of inspiration. Wood spent his remaining years writing and publishing on yoga. He moved to the United States, where he served for a short time as president and dean of the American Academy of Asian Studies in San Francisco, and later moved to Houston, Texas, where he joined the staff of the University of Houston, Texas. Together with his wife, Hilda, Wood helped in the establishment of a Montessori school in Houston, Texas, which was then named after them.

From his earliest times in India, Wood had worked on translations from the Indian classics, such as the Garuda Purana. At the end of the 1920s, he began a thorough study of the Yoga classics with the assistance of several Hindu scholars. These studies resulted in the publication of numerous original translations of famous yoga texts such as the Bhagavad Gita, Patañjali's Yoga Sutras, Shankara's Viveka Chudamani, among others. In his own commentaries to these translations, Wood tried to make the philosophical ideas contained therein applicable to modern life. His writings are, however, not merely of a theoretical or speculative nature, but contain many references to his own practical experiences in these matters. Taken in combination with his concise treatises of the yoga discipline as a whole (such as the volume Yoga, Penguin Books,1959/62), and his earlier writings on concentration and memory training, Wood's works contain a complete introduction to Raja Yoga, or the yoga of the mind. Because of his sparing use of Sanskrit expressions they are easily accessible by western readers.

Wood died on September 17, 1965, only days after finishing his translation of Shankara's Viveka Chudamani, which was posthumously published unter the title The pinnacle of Indian thought.

C.

W. LEADBEATER

Ernest Wood

[ What follows is an appreciation of C. W. Leadbeater by Professor Ernest Wood, which was found amongst Professor Wood’s papers and was sent to N. Sri Ram by Dr. Lawrence

J. Bendit.]

Bishop Leadbeater was what I call a great man, by which I mean that the consuming desire of his life was the

welfare of humanity, and with him no personal pleasure could be allowed to interfere with that. He was, I am sure, innocent of the sexual passion and interests of which he was accused by persons

without sufficient discrimination, but being a man of great courage, independent judgment, unfailing brotherliness and love of personal freedom, in his younger days he dealt with sexual problems

of others according to his own knowledge and judgment. He was not a man who had developed any particular talent greatly, because he was essentially responsive to the constant calls of other

people, his virtues being essentially those of the best type of country clergyman. He did not, therefore, try and sway large numbers of people, but worked in small groups where this affection

could have full effect, and in the belief that the good he could do there would spread. When self-seeking or pushful people tried to intrude into these small circles or impeded his work, he could

and did get angry, but this was not deep-seated and he would not deliberately have hurt his worst enemy… His secondary interest was knowledge… In it he showed a definite scientific attitude, by

which I mean that he would be very careful about details and would go into his enquiries with an idea of finding facts, not of confirming preconceived ideas. I call this his secondary interest

because generally he would delay or set aside this work if there were occasion to attend to young people or his personal groups. I was impressed by his general interest in what he found in the

course of his clairvoyant work, and only after some time did I come to think that his personal likes and dislikes might be coloring the results to some extent. My views with regard to this work

now, after looking into it in retrospect, are that there were certainly a number of definite errors…

Meher Baba's Life & Travels

Meher Baba's Life & Travels