Born :

Died :

BRITISH

Orchestra conductor

1931

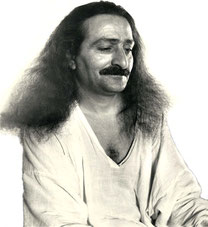

The orchestra conductor Leopold Stokowski came to meet Baba at the Astor Hotel on November 25th. The following is their conversation:

Stokowski asked Baba, "How can unity be brought about between East and West, especially when the conditions prevailing are quite contrary?"

Baba dictated, "Reconciliation is possible and can be achieved. It can and will be done. I will do it. It is the internal that matters, not the external. When the soul becomes enlightened, it experiences Reality. And however diverse the conditions may be, everything is seen and experienced as one."

Stokowski said, "I have asked many wise people the same question, but none could satisfy me as your clear-cut answer has."

"It is not a matter of thought or feeling. I know and do," Baba replied.

"Is outward beauty necessary for the inner?" Stokowski asked.

"From your standpoint as an artist, you see all that is outwardly beautiful in nature and, through it, the internal. It is good, but once the inner perception is gained, nothing remains of external beauty or ugliness; all is alike."

Lord Meher Volume

4, Page 1488

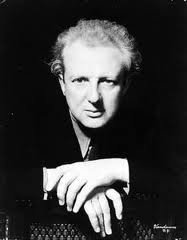

Leopold Anthony Stokowski (April 18, 1882 – September 13, 1977) was a British-born, naturalised American orchestral conductor, well known for his free-hand performing style that spurned the traditional baton and for obtaining a characteristically sumptuous sound from many of the great orchestras he conducted.

In America, Stokowski performed with the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the NBC Symphony Orchestra, New York Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra, the Houston Symphony Orchestra, the Symphony of the Air and many others. He was also the founder of the All-American Youth Orchestra, the New York City Symphony, the Hollywood Bowl Symphony Orchestra and The American Symphony Orchestra. He conducted the music for and appeared in Disney's Fantasia along with being portrayed by Bugs Bunny in the 1949 Looney Tunes episode Long-Haired Hare. Stokowski, who made his official conducting debut in 1909, appeared in public for the last time in 1975 but continued making recordings until June 1977, a few months before his death at the age of 95.

Early life

Stokowski was the son of an English-born cabinetmaker with Polish heritage, Kopernik Józef Bolesławowicz Stokowski, and his Irish-born wife Annie Marion Stokowska, née Moore. Stokowski was born Leopold Anthony Stokowski, though on occasion in later life he altered his middle name to Antoni and added the family names Stanisław Bolesławowicz. There is some mystery surrounding his early life. For example, he spoke with a slight accent, though he was born and raised in London, England.[1] In addition, on occasion, Stokowski gave his birth year as 1887 instead of 1882, as in a letter to the Hugo Riemann Musiklexicon in 1950, which also gave his birthplace as Kraków, Poland. Nicolas Slonimsky, editor of Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians received a letter from a Finnish encyclopedia editor that said, "The Maestro himself told me that he was born in Pomerania, Germany, in 1889."

However, Stokowski's birth certificate (signed by J. Claxton, the registrar at the General Office, Somerset House, London, in the parish of All Souls, County of Middlesex) gives his birth on April 18, 1882, at 13 Upper Marylebone Street (now New Cavendish Street), in the Marylebone District of London. Stokowski was named after his Polish-born grandfather Leopold, who died in the English county of Surrey on January 13, 1879, at the age of 49.[2] The "mystery" surrounding his origins and accent is clarified in Oliver Daniel's 1000-page biography "Stokowski – A Counterpoint of View" (1982), in which (in Chapter 12) Daniel reveals that Stokowski came under the influence of his first wife, the pianist Olga Samaroff. Samaroff, née Hickenlooper, was from the American midwest,and adopted a more exotic-sounding name to further her career. For professional and career reasons, she "urged him to emphasize only the Polish part of his background" once he became a resident of the United States.

Stokowski studied at the Royal College of Music, which he first enrolled in 1896 at the age of thirteen, making him one of the youngest students to do so. In his later life in America, Stokowski would perform six of the nine symphonies composed by his fellow organ student Ralph Vaughan Williams. Stokowski sang in the choir of the St. Marylebone Church, and later he became the Assistant Organist to Sir Walford Davies at The Temple Church. At the age of 16, Stokowski was elected to a membership in the Royal College of Organists. In 1900, Stokowski formed the choir of St. Mary's Church, Charing Cross Road, where he trained the choirboys and played the organ. In 1902, Stokowski was appointed the organist and choir director of St. James's Church, Piccadilly. He also attended The Queen's College, Oxford, where he earned a Bachelor of Music degree in 1903.

Professional career

In New York, Paris, and Cincinnati

In 1905, Stokowski began work in New York City as the organist and choir director of St. Bartholomew's Church. He was very popular among the parishioners, who included members of the Vanderbilt family, but in the course of time, he resigned this position in his quest of a career as an orchestra conductor. Stokowski moved to Paris for additional study in music conducting. There he heard that the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra would be needing a new conductor when it returned from a long sabbatical. In 1908, Stokowski began a campaign to win this conducting position, writing multiple letters to the orchestra's president, Mrs. C. R. Holmes, and traveling all the way to Cincinnati, Ohio, for a personal interview.

Stokowski won out over the other applicants, and he took up his conducting duties in the Fall of 1909. That was the year of his official conducting debut in Paris with the Colonne Orchestra on May 12, 1909, when Stokowski accompanied his bride-to-be, the pianist Olga Samaroff, in Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 1. Stokowski's conducting debut in London took place the following week on May 18 with the New Symphony Orchestra at Queen's Hall.

Stokowski as the new permanent conductor was a great success in Cincinnati, where he introduced the concept of "pop concerts." Starting with his first season in Cincinnati he began championing living composers with performances of music by Richard Strauss, Sibelius, Rachmaninov, Debussy, Glazunov, Saint-Saens and many others. He conducted the American premieres of new works by such composers as Edward Elgar, whose 2nd Symphony was first presented there on November 24, 1911. He was to maintain his advocacy of contemporary music to the end of his career.

However, in early 1912, Stokowski became highly frustrated with the politics of the orchestra's Board of Directors, and he turned in his resignation. There was some dispute over whether to accept this or not, but on April 12, 1912, the Board decided to do so.

At the Philadelphia Orchestra

Two months later, Stokowski was appointed the director of the Philadelphia Orchestra, and he made his conducting debut in Philadelphia on October 11, 1912. This position would bring him some of his greatest accomplishments and recognition. It has been suggested that Stokowski resigned abruptly at Cincinnati, with the hidden knowledge that the conducting position in Philadelphia was his when he wanted it, or as Oscar Levant suggested in his book A Smattering of Ignorance, "he had the contract in his back pocket." Before Stokowski moved into his conducting position in Philadelphia, however, Stokowski sailed back to England to conduct two concerts at the Queen's Hall in London. On May 22, 1912, Stokowski conducted the London Symphony Orchestra in concert which he was to repeat in its entirety 60 years later at the age of 90, and on June 14, 1912, he conducted an all-Wagner concert that featured the noted soprano Lillian Nordica.

Stokowski rapidly gained a reputation as a musical showman. His flair for the theatrical included grand gestures such as throwing the sheet music on the floor to show he did not need to conduct from a score. He also experimented with new lighting arrangements in the concert hall,[3] at one point conducting in a dark hall with only his head and hands lighted, at other times arranging the lights so they would cast theatrical shadows of his head and hands. Late in the 1929-30 symphony season, Stokowski started conducting without a baton. His free-hand manner of conducting soon became one of his trademarks.

On the musical side, Stokowski nurtured the orchestra and shaped the "Stokowski" sound, or what became known as the "Philadelphia Sound".[4] He encouraged "free bowing" from the string section, "free breathing" from the brass section, and continually altered the seating arrangements of the orchestra's sections, as well as the acoustics of the hall, in response to his urge to create a better sound. Stokowski is credited as being the first conductor to adopt the seating plan that is used by most orchestras today, with first and second violins together on the conductor's left, and the violas and cellos to the right. (Preben Opperby's 1982 Stokowski biography reproduces, on page 127, four of Stokowski's various seating plans, of which illustration No. 2 shows the string sections as here described). However, like many other conductors of his generation, Stokowski also became known for modifying the orchestrations of famous compositions by such composers as Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, Sibelius, Johann Sebastian Bach, and Brahms. In one case, Stokowski revised the ending of the Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture, by Tchaikovsky, so that it would close quietly, taking his notion from Modest Tchaikovsky's Life and Letters of Peter Ilych Tchaikovsky (translated by Rosa Newmarch: 1906) that the composer had provided a quiet ending of his own at Balakirev's suggestion. This was in addition to the three different versions of the work made by the composer himself, in 1870, 1871 and 1881. Stokowski made major revisions to Mussorgsky's Night on Bald Mountain, making significant alterations to Rimsky-Korsakov's adaptation of the work, and making it sound, in some places, similar to the original. In the film Fantasia, to conform to the Disney artists' story-line, depicting the battle between good and evil, the performance of Night on Bald Mountain segued into the beginning of Schubert's Ave Maria.

Many serious music critics have been horrified at the liberties Stokowski took—liberties which were common in the nineteenth century, but had mostly died out in the twentieth, when faithful adherence to the composer's scores became more common.[5] However, Stokowski often left scores completely unretouched, particularly those many hundreds of new works which he was conducting for the first time. On the other hand, he was by no means alone in his alterations to more familiar scores. Arturo Toscanini, for example, who had a reputation for "doing as written", was equally adept at making similar changes to composers' scores, as in Tchaikovsky's Manfred symphony, where Toscanini added tam-tam crashes to the end of the first movement, rewrote the wind, brass, and string parts here and there, and cut 100 bars out of the finale. Toscanini's alterations, however, nearly always tended to be much more subtle, and less frequent than Stokowski's.

Stokowski's repertoire was broad and included many contemporary works. He was the only conductor to perform all of Arnold Schoenberg's orchestral works during the composer's own lifetime, several of which were world premieres. Stokowski gave the first American performance of Schoenberg's Gurre-Lieder in 1932. It was recorded "live" on 78 rpm records and remained the only recording of this work in the catalog until the advent of the LP album. Stokowski also presented the American premieres of four of Dmitri Shostakovich's symphonies, Numbers 1, 3, 6, and 11. In 1916, Stokowski conducted the American premiere of Mahler's 8th Symphony, Symphony of a Thousand. He added works by Rachmaninoff to his repertoire, giving the world premieres of his Fourth Piano Concerto, the Three Russian Songs, the Third Symphony, and the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini; Sibelius, whose last three symphonies were given their American premieres in Philadelphia in the 1920s. Also, Igor Stravinsky, many of whose works were also given their first American performances by Stokowski. In 1922, he introduced The Rite of Spring to America, gave its first staged performance there in 1930 with Martha Graham dancing the part of The Chosen One, and at the same time made the first American recording of the work.

Seldom an opera conductor, Stokowski did give the American premieres in Philadelphia of the original version of Mussorgky's Boris Godunov (1929) and Alban Berg's Wozzeck (1931). Many works by such composers as Arthur Bliss, Max Bruch, Ferruccio Busoni, Carlos Chávez, Aaron Copland, George Enescu, Manuel de Falla, Paul Hindemith, Gustav Holst, Gian Francesco Malipiero, Nikolai Myaskovsky, Walter Piston, Francis Poulenc, Sergei Prokofiev, Maurice Ravel, Ottorino Respighi, Albert Roussel, Alexander Scriabin, Elie Siegmeister, Karol Szymanowski, Edgard Varèse, Heitor Villa-Lobos, Anton Webern, and Kurt Weill, amongst countless other lesser names, received their American premieres under Stokowski's direction in Philadelphia.

In 1933, Stokowski started "Youth Concerts" for younger audiences, which are still a tradition in Philadelphia and many other American cities, and fostered youth music programs.

After disputes with the board, Stokowski began to withdraw from involvement in the Philadelphia Orchestra from 1936 onwards, allowing his co-conductor Eugene Ormandy to gradually take over. Stokowski shared principal conducting duties with Ormandy from 1936–1940; Stokowski did not appear with the Philadelphia Orchestra from December 6, 1940, when he premiered Schoenberg's Violin Concerto with Louis Krasner, until February 12, 1960, when he guest-conducted the Philadelphia in works of Mozart, de Falla, Respighi, and in a legendary performance of the Shostakovich Fifth Symphony, arguably the greatest by Stokowski, which has been circulated privately among collectors but never issued commercially.

Stokowski appeared as himself in the motion picture The Big Broadcast of 1937, conducting two of his Bach transcriptions. That same year he also conducted and acted in One Hundred Men and a Girl, with Deanna Durbin and Adolphe Menjou. In 1939, Stokowski collaborated with Walt Disney to create the motion picture for which he is best known: Fantasia. He conducted all the music (with the exception of a "jam session" in the middle of the film) and included his own orchestrations for the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor and Night on Bald Mountain/Ave Maria segments. Stokowski even got to talk to (and shake hands with) Mickey Mouse on screen, although he would later say with a smile that Mickey Mouse got to shake hands with him. Most of the music was recorded in the Academy of Music, using multi-track stereophonic sound. Stokowski also appeared in the 1947 film Carnegie Hall along with Bruno Walter, Fritz Reiner, Jascha Heifetz, Arthur Rubinstein, Ezio Pinza and other great classical musicians of the day.

On his return in 1960, Stokowski appeared with Philadelphia Orchestra as a guest conductor. He also made two LP recordings with them for Columbia Records, one including a performance of Manuel de Falla's El amor brujo, which he had introduced to America in 1922 and had previously recorded for RCA Victor with the Hollywood Bowl Symphony Orchestra in 1946, and a Bach album which featured the 5th Brandenburg Concerto and three of his own Bach transcriptions. He continued to appear as a guest conductor on several more occasions, his final Philadelphia Orchestra concert taking place in 1969.

In honor of Stokowski's vast influence on music and the Philadelphia performing arts community, on February 24, 1969, he was awarded the prestigious University of Pennsylvania Glee Club Award of Merit[6]. Beginning in 1964, this award was "established to bring a declaration of appreciation to an individual each year that has made a significant contribution to the world of music and helped to create a climate in which our talents may find valid expression."

All-American Youth Orchestra

With his Philadelphia Orchestra contract having expired in 1940, Stokowski immediately formed the All-American Youth Orchestra, its players' ages ranging from 18 to 25. It toured South America in 1940 and North America in 1941 and was met with rave reviews. Although Stokowski made a number of recordings with the AAYO for Columbia, the technical standard was not as high as had been achieved with the Philadelphia Orchestra for RCA Victor. In any event, the AAYO was disbanded when America entered the war, and plans for another extensive tour in 1942 were abandoned.

NBC Symphony Orchestra

During this time, Stokowski also became chief conductor of the NBC Symphony Orchestra on a three-year contract (1941–1944). The NBC's regular conductor, Arturo Toscanini, did not wish to undertake the 1941-42 NBC season because of friction with NBC management, though he did accept guest engagements with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Stokowski conducted a great deal of contemporary music with the NBC Symphony, including the U.S. premiere of Prokofiev's Alexander Nevsky in 1943, the world premieres of Schoenberg's Piano Concerto (with Eduard Steuermann) and George Antheil's 4th Symphony, both in 1944, and new works by Alan Hovhaness, Stravinsky, Hindemith, Milhaud, Howard Hanson, William Schuman, Morton Gould and many others. He also conducted several British works with this orchestra, including Vaughan Williams' 4th Symphony, Holst's The Planets, and George Butterworth's A Shropshire Lad. Stokowski also made a number of recordings with the NBC Symphony for RCA Victor, including Tchaikovsky's 4th Symphony, a work which was never in Toscanini's repertoire, and Stravinsky's Firebird Suite, recorded in 1941 or 1942. Toscanini then returned as co-conductor of the NBC Symphony with Stokowski for the remaining two years of the latter's contract.

New York City Symphony Orchestra

In 1944, on the recommendation of Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, Stokowski helped form the New York City Symphony Orchestra, which they intended would make music accessible for middle-class workers. Ticket prices were set low, and performances took place at convenient, after-work hours. Many early concerts were standing room only; however, a year later in 1945, Stokowski was at odds with the board (who wanted to trim expenses even further) and he resigned. Stokowski made three 78pm sets with the New York City Symphony for RCA: Beethoven's 6th Symphony, Richard Strauss's Death and Transfiguration, and a selection of orchestral music from Georges Bizet's Carmen.

Hollywood Bowl Symphony Orchestra

In 1945, he founded the Hollywood Bowl Symphony Orchestra. The

orchestra lasted for two years before it was disbanded for live concerts, but not for recordings, which continued well into the 1960s. Stokowski's own recordings (made in 1945-46) included

Brahms's 1st Symphony, Tchaikovsky's

Pathetique Symphony and a number of short popular pieces. Some of Stokowski's open-air HBSO concerts were broadcast

and recorded, and have been issued on CD, including a collaboration with Percy Grainger on Edvard Grieg's Piano Concerto in A minor in the summer of 1945. (It began giving live concerts again as the "Hollywood Bowl Orchestra" in

1991, under John Mauceri)[7].

There was a 1949 cartoon spoof of Stokowski at the Bowl with Bugs Bunny playing the conductor in "Long-Haired Hare" by Chuck Jones.[8]

New York Philharmonic

He continued to appear frequently with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, both at the Hollywood Bowl and other venues. Then in 1946 Stokowski became a chief Guest Conductor of the New York Philharmonic. His many "first performances" with them included the U.S. Premiere of Prokofiev's 6th Symphony in 1949. He also made many splendid recordings with the NYPO for Columbia, including the world premiere recordings of Vaughan Williams's 6th Symphony and Olivier Messiaen's L'Ascension also in 1949.

International career

However, when in 1950 Dimitri Mitropoulos was appointed Chief Conductor of the NYPO, Stokowski began a new international career which commenced in 1951 with a nation-wide tour of England: during the Festival of Britain celebrations he conducted the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra at the invitation of Sir Thomas Beecham. It was during this first visit that he made his debut recording with a British orchestra, the Philharmonia, of Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade. During that same summer he also toured and conducted in Germany, Holland, Switzerland, Austria, and Portugal, establishing a pattern of guest-conducting abroad during the summer months while spending the winter seasons conducting in the USA. This scheme was to hold good for the next 20 years during which Stokowski conducted many of the world's greatest orchestras, simultaneously making recordings with them for various labels. Thus he conducted and recorded with the main London orchestras as well as the Berlin Philharmonic, the Suisse Romande Orchestra, the French National Radio Orchestra, the Czech Philharmonic, the Hilversum (Netherlands) Radio Philharmonic, and so on.

Symphony of the Air, Houston Symphony Orchestra

Stokowski returned to the NBC Symphony Orchestra in 1954 for a series of recording sessions for RCA. The repertoire included Beethoven's 'Pastoral' Symphony, Sibelius's 2nd Symphony, Acts 2 and 3 of Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake and highlights from Saint-Saëns's Samson and Delilah with Risë Stevens and Jan Peerce. After the NBC Symphony Orchestra was disbanded as the official ensemble of the NBC radio network, it was re-formed as the Symphony of the Air with Stokowski as notional Music Director, and as such performed many concerts and made recordings from 1954 until 1963. The U.S. premiere in 1958 of Turkish composer Adnan Saygun's Yunus Emre Oratorio is among them. He made a series of Symphony of the Air recordings for the United Artists label in 1958 which included Beethoven's 7th Symphony, Shostakovich's 1st Symphony, Khatchaturian's 2nd Symphony and Respighi's The Pines of Rome.

From 1955 to 1961, Stokowski was also the Music Director of the Houston Symphony Orchestra. For his debut appearance with the orchestra he gave the first performance of the Symphony No. 2 Mysterious Mountain by Alan Hovhaness – one of many living American composers whose music he championed over the years. He also gave the U.S. premiere in Houston of Shostakovich's 11th Symphony (April 7, 1958) and made its first American recording on the Capitol label. Stokowski's other recordings with the Houston Symphony included Carl Orff's Carmina Burana and his own edition of Reinhold Glière's Symphony No. 3 Ilya Murometz, both for Capitol; and Brahms's 3rd Symphony and Bartok's Concerto for Orchestra for Everest.

American Symphony Orchestra and London

In 1960, Stokowski made one of his infrequent appearances in the opera house, when he conducted Giacomo Puccini's Turandot at the New York Metropolitan, in memorable performances with a cast that

included Birgit Nilsson, Franco Corelli and Anna Moffo. In 1962, at the age of 80, Stokowski founded the American

Symphony Orchestra. His championship of the 20th century composer remained undiminished and perhaps his most celebrated premiere with the American Symphony Orchestra was of Charles Ives's 4th Symphony in 1965, which he also recorded for CBS.

Stokowski served as Music Director for the ASO until May 1972 when, at the age of 90, he returned to live in England. One of his notable British guest conducting engagements in the 1960s was the

first Proms performance of Gustav Mahler's

Second

Symphony, Resurrection, since issued on CD.[9]

He continued to conduct in public for a few more years, but failing health forced him to only make recordings. An eyewitness said that Stokowski often conducted sitting down in his later years; sometimes, as he became involved in the performance, he would stand up and conduct with remarkable energy. His last public appearance in the UK took place at the Royal Albert Hall, London, on May 14, 1974. Stokowski conducted the New Philharmonia in the 'Merry Waltz' of Otto Klemperer (in tribute to the orchestra's former Music Director who had died the previous year), Vaughan Williams's Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis, Ravel's Rapsodie espagnole and Brahms's 4th Symphony. Stokowski's very last public appearance took place during the 1975 Vence Music Festival in the South of France, when on July 22 he conducted the Rouen Chamber Orchestra in several of his Bach transcriptions.

Recordings

Stokowski made his very first recordings, with the Philadelphia Orchestra, for the Victor Talking Machine Company in October 1917, beginning with two of Brahms' Hungarian Dances. Other works recorded in the early sessions were the scherzo from Mendelssohn's A Midsummer Night's Dream incidental music and "Dance of the Blessed Spirits" from Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice.[10] He found ways to make the best use of the acoustical process, until electrical recording was introduced by Victor in the spring of 1925. Stokowski conducted the first orchestral electrical recording to be made in America (Saint-Saens's Danse Macabre) in April 1925. The following month Stokowski recorded Marche Slave by Tchaikovsky, in which he increased the double basses to best utilize the lower frequencies of early electrical recording. Stokowski was also the first conductor in America to record all four Brahms symphonies (between 1927 and 1933). He made the first U.S. recordings of the Beethoven 7th and 9th Symphonies, Antonín Dvořák's New World Symphony, Tchaikovsky's 4th Symphony and Nutcracker Suite, César Franck's Symphony in D minor, Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade, Rachmaninoff's 2nd Piano Concerto (with the composer as soloist), Sibelius's 4th Symphony (its first recording), Shostakovich's 5th and 6th Symphonies, and many shorter works.

His early recordings were made at Victor's Camden, New Jersey studios but then, in 1927, Victor began recording the orchestra in the Academy of Music in Philadelphia. Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra later participated in long playing, high fidelity, and stereophonic experiments, during the early 1930s, mostly for Bell Laboratories. (Victor even released some LPs at this time, which were not commercially successful because they required special, expensive phonographs that most people could not afford during the Great Depression.) Stokowski recorded prodigiously for various labels until shortly before his death, including RCA Victor, Columbia, Capitol, Everest, United Artists, and Decca/London 'Phase 4' Stereo.

His first commercial stereo recordings were made in 1954 for RCA Victor with the NBC Symphony Orchestra, devoted to excerpts from Prokofiev's ballet Romeo and Juliet and the complete one-act ballet Sebastian by Gian Carlo Menotti.

From 1947-1953 Stokowski recorded for RCA Victor with a specially-assembled 'ad hoc' band of players drawn principally from the New York Philharmonic and NBC Symphony. The LPs were labelled as being played by 'Leopold Stokowski and his Symphony Orchestra' and the repertoire ranged from Haydn (his Imperial Symphony) to Schoenberg (Transfigured Night) by way of Schumann, Liszt, Bizet, Wagner, Tchaikovsky, Debussy, Vaughan Williams, Sibelius and Percy Grainger.

His Capitol recordings in the 1950s were distinguished by the use of three-track stereophonic tape recorders. Typically, Stokowski was very careful in the placement of musicians during the recording sessions and consulted with the recording staff to achieve the best possible results. Some of the sessions took place in the ballroom of the Riverside Plaza Hotel in New York City in January and February 1957; these were produced by Richard C. Jones and engineered by Frank Abbey with Stokowski's own orchestra, which was typically drawn from New York musicians (primarily members of the Symphony of the Air). The CD reissue by EMI included selections originally released on two LPs -- The Orchestra and Landmarks of a Distinguished Career -- and featured music of Dukas, Barber, Richard Strauss, Harold Farberman, Vaughan Williams, Vincent Persichetti, Tchaikovsky, Mussorgsky, Debussy, Bach (as arranged by Stokowski), and Sibelius.[11] Although he officially used the Ravel orchestration of the finale to Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition in his 1957 Capitol recording, he did add a few additional percussion instruments to the score. His Capitol recording of Holst's The Planets was made with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra. EMI, which acquired Capitol and Angel Records in the 1950s, has reissued many of Stokowski's Capitol recordings on CD.

All of the music that Stokowski conducted in Fantasia was released on a 3-LP set by Disneyland Records, in the 1957 soundtrack album made from the film. After stereo became possible on phonograph records, the album was released in stereo on Buena Vista Records. With the advent of compact discs, it appeared on a 2-CD Walt Disney Records set, in conjunction with the film's 50th anniversary.

Other labels for which Stokowski recorded in the late 1950s included Everest, noted for its use of 35 mm film instead of tape and the resulting highly vivid sound. The most notable of these was a coupling of Tchaikovsky's Francesca da Rimini and Hamlet with Stokowski conducting the New York Stadium Symphony Orchestra (the summer name for the New York Philharmonic). Other remarkable Everest's recordings of Stokowski conducting the New York Stadium Symphony Orchestra are Villa-Lobos' tone poem Uirapuru, Shostakovich's Symphony No. 5 and Prokofiev's ballet suite Cinderella.

Stokowski as transcriber

Stokowski was celebrated as a transcriber of music originally written in other forms. His catalogue includes about 200 orchestral arrangements, nearly 40 of which are transcriptions of the works of J. S. Bach. During the 1920s and '30s, Stokowski arranged many of Bach's keyboard and instrumental works, as well as songs and cantata movements, for very large forces as well as just for strings alone. The most famous of them, the Toccata and Fugue in D minor, originally for organ, served as the opening item in Walt Disney's Fantasia and brought this magnificent music to a wide audience. Much admired in their day, these transcriptions are again being played now, and conductors such as Wolfgang Sawallisch, Matthias Bamert, Esa-Pekka Salonen, Seiji Ozawa, Erich Kunzel and Jose Serebrier are among many who have performed and recorded Stokowski's Bach transcriptions. These arrangements have been considered by some purists to be bastardizations of the original works, though as Stokowski pointed out, Bach himself was an inveterate transcriber of the music of others, notably Antonio Vivaldi. Today the organ works of Bach are widely heard in their original form via recordings and concerts, much more so than during Stokowski's time. Whether his transcriptions encouraged this resurgence of interest in Bach's organ music is a matter of debate. However, in this context it should be noted that Stokowski was by no means the only orchestrator of Bach's music. Other conductors who have arranged Bach for symphonic forces include John Barbirolli, Dimitri Mitropoulos, Eugene Ormandy, Otto Klemperer, Erich Leinsdorf and Malcolm Sargent, while composers' arrangements include those by Elgar, Schoenberg, Respighi, Reger, Holst, and many others. In general, modern CD recordings of these and of Stokowski's versions have been given a very warm welcome by today's critics. For example, as Raymond Tuttle wrote in Fanfare: "It is worth remembering that many people would never have found a doorway into the world of Bach had Stokowski not put one there for them. Let's not be snobs about it: Stokowski's Bach is musical sorcery of the best sort."

On the other hand, former New York Times critic Harold C. Schonberg was not overly enthusiastic about them, even going so far as to say in his book Facing the Music that it was wrong to prefer Stokowski's Bach to the real thing.

In 1939, Stokowski also made his own orchestration of Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition, in which he omitted two of the movements "Tuileries", and "The Marketplace at Limoges" from the score. The composer and arranger Lucien Cailliet, a member of the Philadelphia Orchestra who also acted as "house arranger", had assisted Stokowski in the copying of many of Stokowski's transcriptions, something which led to the incorrect assumption that they were Cailliet's work and not Stokowski's. In fact, many of Stokowski's penciled manuscripts still survive in the Stokowski Collection at the University of Pennsylvania. It was from these that Cailliet made good ink copies in his excellent calligraphic hand, and thus started the unfounded rumour that Stokowski's transcriptions were not his own work. Cailliet had actually created his own orchestration of Pictures at an Exhibition in 1936, and as Ormandy's RCA Victor recording shows, it is quite different from Stokowski's arrangement. In recent years Stokowski's version has become an occasional popular alternative to Ravel's, both in the concert-hall and on disc, having been recorded by Gennady Rozhdestvensky, Oliver Knussen, Matthias Bamert, Jose Serebrier, and James Sedares.

Stokowski also took passages from Wagner operas and seamlessly wove them into purely orchestral "Symphonic Syntheses" in which the vocal parts were transferred to the strings or solo instruments. Many of his shorter arrangements, such as those of songs and piano pieces by Schubert, Tchaikovsky and so on, served as "encores" with which he often concluded his concerts, rather in the same manner as Sir Thomas Beecham did with his "lollipops." Many of today's conductors have taken Stokowski's transcriptions into their own repertoire and two of his former assistants, Matthias Bamert and Jose Serebrier, have both made an extensive series of recordings of them (for Chandos and Naxos respectively).

Last years

Stokowski gave his last world premiere in 1973 when, at the age of 91, he conducted Havergal Brian's

28th Symphony in a BBC radio broadcast with the New Philharmonia Orchestra. He continued to make recordings even after he had retired from the concert platform, mainly with the National

Philharmonic, another 'ad hoc' orchestra made up of first-desk players chosen from the main London orchestras. In 1976, he signed a recording contract with CBS Records that would have kept him

active until he was 100 years old.[12] However, he died of a heart attack the following year in Nether Wallop, Hampshire at 95. His very last recordings, made shortly before his death, for Columbia, included performances of the youthful

Symphony in

C by Georges Bizet and Felix Mendelssohn's 4th

Symphony, "Italian", with the National Philharmonic Orchestra in London.[13]

In 1979, the Leopold Stokowski Society was formed in England. In its 30 years existence, until it disbanded in 2009, it issued on Cala Records thirty-five CDs of some of Stokowski's recordings and broadcasts.

Stokowski married three times. His first wife was the American concert pianist Olga Samaroff (born Lucie Hickenlooper), to whom he was married from 1911 until 1923. They had one daughter: Sonya Stokowski, an actress, who married Willem Thorbecke and settled in the U.S. with their four children, Noel, Johan, Leif and Christine. His second wife was Johnson & Johnson heiress Evangeline Love Brewster Johnson, an artist and aviatrix, to whom he was married from 1926 until 1937 (two daughters: Gloria Luba Stokowski and Andrea Sadja Stokowski). His third wife, from 1945 until 1955, was railroad heiress Gloria Vanderbilt (born 1924), an artist and fashion designer (two sons, Leopold Stanislaus Stokowski, b. 1950 and Christopher Stokowski, b. 1952). He also had a much-publicized affair with Greta Garbo during the 1930s.

After he had achieved international fame with the Philadelphia Orchestra, unsubstantiated rumours circulated that he was born "Leonard" or "Lionel Stokes" or that he had "anglicized" it to "Stokes"; this canard is readily disproved by reference not only to his birth certificate and those of his father, younger brother, and sister (which show Stokowski to have been the genuine Polish family name), but also by the Student Entry Registers of the Royal College of Music, Royal College of Organists, and The Queen's College, Oxford, along with other surviving documentation from his days at St. Marylebone Church, St. James's Church, and St. Bartholomew's in New York City.[14][not specific enough to verify] Upon his arrival in America, however, he briefly spelled his name as Stokovski to ensure that people could pronounce it correctly.

After Stokowski's death, Tom Burnam writes, the "concatenization of canards" that had arisen around him was revived—that his name and accent were phony; that his musical education was deficient; that his musicians did not respect him; that he cared about nobody but himself. Burnam suggests that there was a dark, hidden reason for these rumors. Stokowski deplored the segregation of symphony orchestras in which women and minorities were excluded, and, so Burnam claims, the bigots got revenge by slandering Stokowski.

Nevertheless, and notwithstanding the claims made by Tom Burnam, attitudes towards Stokowski have changed dramatically over the years since his death. In 1999, for Gramophone magazine, and quoted again in his notes for the Cala CD of Stokowski's recording of Elgar's Enigma Variations, David Mellor wrote: "One of the great joys of recent years for me has been the reassessment of Leopold Stokowski. When I was growing up there was a tendency to disparage the old man as a charlatan. Today it is all very different. Stokowski is now recognised as the father of modern orchestral standards. He possessed a truly magical gift of extracting a burnished sound from both great and second-rank ensembles. He also loved the process of recording and his gramophone career was a constant quest for better recorded sound. But the greatest pleasure of all for me is his acceptance now as an outstanding conductor of nineteenth- and twentieth-century music, including a lot that was at the cutting edge of contemporary achievement."

Mellor's words have been echoed by many other modern writers, such as Robert Matthew-Walker of International Record Review, whose comments fairly represent the opinions of many critics today: "That Stokowski was a great musician is beyond doubt; that he was a great conductor is self-evident; that he always placed himself at the service of the music may be more contentious to some ears, but in keeping with the established norms of the age into which he was born and musically nurtured, Stokowski remained loyal to those precepts from which we, in an era far removed from their prevalence, can still learn and draw aesthetic sustenance."

Stokowski is buried at East Finchley Cemetery, in north London.

Meher Baba's Life & Travels

Meher Baba's Life & Travels