Born :

Died :

Aristocrat

RUSSIAN-AMERICAN

1935![]()

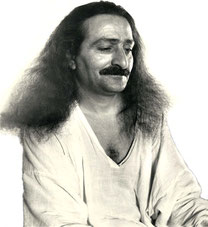

On August 14th, Baba also dictated this reply to a friend of Nadine Tolstoy's, Grand Duchess Marie, a Russian aristocrat:

"Many bitter experiences of the past often open new vistas that help one to understand things better, as they really are not as they appear. Your hard trials in life have been instrumental in making you what you are now, a changed being with a different outlook on life, and ushering you into the spiritual reality where you alone will find peace, bliss and love".

1936

After two days, the group went to stay at a bungalow in Bhandardara where the climate was cooler and more comfortable. From Nasik, Baba came to stay at Bhandardara for five days on December 14th, accompanied by Bhagirath. Two days later, Garrett Fort, Nadine Tolstoy and Grand Duchess Marie arrived from America on the ship Conte Verde.

An acquaintance of Nadine Tolstoy's, Duchess Marie was a Russian aristocrat who had also immigrated to America. She was a wealthy lady who had become a freelance journalist and had corresponded with Baba. However, after meeting Baba, she decided not to stay as she became uneasy about what living conditions would be like in Nasik. She was afraid that life in an ashram would mean a loss of her privacy and individuality. Because she was wealthy and had been exploited, the Duchess suspected Baba of being like Rasputin when he advised her to abandon her plans to travel in India and come instead to Nasik for a rest, inviting her to help with the magazine he intended starting. The Duchess mistrusted Baba's intention and mistook this as his attempt to launch a project using her name. Failing to see the great opportunity before her, the Duchess stayed at Bhandardara for only four days and traveled on in India, never to be in Baba's contact again.

Lord Meher Volume 6, Page

2054

TRAVELLING TO INDIA

Departed New York 1st December 1936 and arrived in Bombay 14th December 1936.

(Originally published in the European Royal History Journal, Issues VIII & IX.)

Perhaps it was because she had never had much of a childhood herself that Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna of Russia, daughter of Grand Duke Paul Aleksandrovich and Aleksandra of Greece, had no great affinity for the toddlers of this world. She knew this all too well. All the hurtful ways adults had of dealing with her in her own infancy, she wrote, were strangely to shape all her relations with children - even with her own.

Certainly, in later years, on coming to know her son by Prince Vilhelm of Sweden, Count Lennart Bernadotte af Wisborg, Marie obliged the tall young man to address her by her given name rather than 'mother', a requirement that seems not to have sat comfortably with either the boy or the man. If this appears strange, it is well to remember that Marie's mother, after all, had died tragically young, following the birth of a son, Grand Duke Dimitri, when Marie was less than two years old; and not long after, her father took up with a beautiful lady whose commoner origins eventually got both sent into Parisian exile. Marie and Dimitri, traumatized, were taken into the bosom of their father's family, the Romanovs, whose childrearing techniques, generally speaking, had not the best of track records, and specifically into the bosom of a marriage that could hardly be called the best example for adults, let alone bewildered children.

On this unpromising anvil Marie forged a character that was nothing if not self-reliant. But her lifelong inability to relate to children was to prove that however lucky she was to have found a lifeboat, come the sinking of the Titanic of Russia's ruling caste after 1918, the few treasures she saved from the wreckage were wanting when compared to those she had long ago left behind. Luckily for Marie, her own child had no intention of doing the same.

'Born in 1890', Marie writes in her first volume of memoirs, The Education of a Princess, 'I have stepped through the ages." Her earliest memories were of lazy country estates populated by armies of servants, fortresses haunted by reverberations of past strife and bloodshed, of palaces that were such confections of gold, silver, and marble that they outdistanced the fairy tale fastnesses described by the most fantastical nyanyas. As she wrote of these things, looking out on Depression-era New York's traffic-clogged streets and towering buildings, Marie must indeed have wondered which was real and which make-believe.

In the Russia of 1890 (as in the Russia of a century later), life would remain mediaeval in certain respects for the many and up-to-date for a relative few. Marie belonged to the second category in so far as she grew up with conveniences'electric light, telephones, automobiles'that remained mysterious if not terrifying to the majority of her cousin Tsar Nicholas II's subjects. But where the Romanov family regulations were concerned, mediaevalism enjoyed a biblical life-span. The Fundamental Laws, scripted by Tsar Paul I, threw the book at all sorts of troubles which he wished never to see repeated. Women, for example, were to be barred from ruling'one didn't want another Catherine the Great roving unchecked upon the face of Holy Russia. For added difficulty, spouses taken by all members of the ruling family were to be equal-born. By the end of the 19th century, this requirement had set up a towering standard of best behavior, directed mainly toward the males of the family, which many of them opted to sidestep by taking morganatic wives. What a Grand Duke gained in domestic bliss, he and his children by such a woman lost in giving up all rights to the Russian throne or the family name.

This risk Marie's father, Grand Duke Paul Aleksandrovich, proved himself willing to run. His first wife had fallen ill shortly after arriving for a visit to Ilinskoie, the unpretentious country estate of her brother-in-law Grand Duke Serge Aleksandrovich outside Moscow, in September 1891. Six days in a coma, Aleksandra was delivered of a premature son, Grand Duke Dmitri, and then died. No one could believe that the lovely Grand Duchess Paul, only 21 years old, was no more, least of all her adoring husband. At the funeral in Peter and Paul Cathedral, Paul couldn't bear to have the coffin closed, and Serge had to take him in his arms and lead him away.

Of the many failings that can be ascribed to those Romanov princes who married or mistressed in defiance of the Fundamental Laws, coldness of heart was rarely among them. When four years into his widowerhood Grand Duke Paul met Mme Eric von Pistolkors, an elegant Petersburg socialite of noble Hungarian ancestry, he and the future Princess Paley literally fell in love at first sight. A natural son, Vladimir, brought about Olga von Pistolkors' divorce from her Cheval Garde officer husband in 1897; and in autumn 1902, the Grand Duke was married to his lady, in Livorno, Italy, by an Orthodox priest ignorant of their identities. Unable to return to Russia, the couple took up residence in a mansarded villa in Paris, No. 2 Avenue Victor Hugo, where it seemed they were to dwell happily ever after.

Having been informed by mail of their father's marriage, and devastated by the news, the 12 year old Marie and her 11 year old brother were placed in the care of their uncle, Grand Duke Serge, and his wife, the coldly beautiful Princess Elisabeth (Ella) of Hessen, sister of Empress Aleksandra. Marie claimed her childhood ended in this year of 1902, but she describes in her memoirs even before that a girl not so much infant as miniature adult. Some instinct warned her early on that the way of life led by her family was off kilter compared to the rest of the world, and was not to last. Indeed, close to this time she pictures herself, sitting on the floor of the nursery, attempting to button her own boots. In the event of a revolution, a modern princess had to know how to look after herself.

This Marie was to do very well even before revolutions began to rain down. She lived with an aunt who when not ignoring her entirely seems to have been as chilly as her sister was overwrought. Once Marie found Ella wearing court dress, her swan-like neck emblazoned with sapphires, and impulsively kissed the pale flesh under the gorgeous stones. Ella's response was to stare coldly, stinging her niece to the heart.

Uncle Serge was far more complicated. Historians generally accept that he was homosexual, without pointing out how much of his odd behavior may have been occasioned by the fear and self-loathing he, in a family that did not appreciate men of his kind, probably lived with on a daily basis. He ran Ilinskoie like a mother superior her convent'loving and fierce by turns. When he was angry, Marie remembered, Serge's lips became 'one crisp straight line', while his eyes were 'little hard points of light.' Every detail of the house, down to what his wife wore, came under those hard little points. Ella, Marie felt, was remote for a good reason: Serge drove her into the only refuge she could find'herself. Though toward herself and her brother Uncle Serge was capable of an affection almost maternal, Marie freely admits she could not entirely disagree with a world that thought him heartless, self-centered and cruel.

Transferred to the larger world, Serge's petty tyranny gained him many enemies'some in the Imperial family itself had questioned the sanity of Ella's yen to marry him years before. It wasn't just his part in the mishandling of the security arrangements leading to the 1896 Khodynka Field disaster at his nephew Nicholas II's coronation, that first shadow on 'Nicky's"twilit reign, that made Serge a figure much hated in Moscow, particularly among the sort of bomb-throwing political dissenters who had assassinated his father. His cousin, Grand Duke Aleksander Mikhailovich, claimed to be unable to find 'a single redeeming feature in his character'. Serge was 'obstinate, arrogant, disagreeable', wrote Aleksander Mikhailovich, 'flaunting his many peculiarities in the face of an entire nation." Aleksander Mossolov of the Court Chancellery noted Serge's extremely reactionary nature, never hesitating to expound his 'die-hard ideas"to his nephew the Tsar (who merely smiled politely in response). More even-handed yet perhaps even more penetrating in her critique of Serge was the witty American Duchess of Marlboro, the former Consuelo Vanderbilt, who thought Serge gave off a palpable 'air of evil'. He would have made an excellent Mephistopheles, she mused. Some dissatisfied Russians took that impression a little more seriously. Early in 1905, amid worsening tensions over Russia's failure to master Japan in battle, Marie and Dmitri were taken to stay with Ella and Serge in the unheatable rooms of the Kremlin's Nicholas Palace, safe'so it was thought'from the revolutionary disorders that had been plaguing Moscow the past months. On 16 February, they and Serge emerged from the thick walls of the Kremlin to hear Feodor Chaliapin sing at a war benefit. As Marie was to discover, only her and Dmitri's presence prevented the terrorists dogging her uncle's heels from throwing a bomb into his carriage that very night.

Two days later, Marie was sitting at her lessons, her schoolroom window opening to a wide view of the Kremlin square covered in snow. Her uncle had just left the palace in his sleigh, to attend to business in the city. Suddenly, an explosion rattled the panes. She remembered clouds of startled crows, circling madly around St Ivan's steeple, and her aunt Ella being borne away in a sleigh, Marie's governess in tow. It returned with the governess alone, who shakingly took the children away from the window. Later, Marie and Dmitri viewed a pitiful bundle of coat-covered remains, beside which Ella prayed'she who had gathered them up, a hand here, there a foot, in her cloak, on the bloody square. 'He loved you so,"Ella told them, holding their heads near to her. 'He loved you so." By the time night fell, Ella had softened'she asked to sleep in Marie's room and wept against her on the bed'and began to radiate the intense passion for life's matters of ultimate concern that would lead her to visit and forgive her husband's murderer and found a convent in which she, like her namesake St. Elisabeth of Hungary, worked for general and particular salvation.

Not that the nun's habit that seemed to bequeath fresh candor and sense on Ella was entirely wonder-working. Largely through Ella's dictation, backed up by her prim and proper sister Irene of Prussia, Marie was to find herself propelled into another unfortunate domestic arrangement in a household not her own. Perhaps Marie's own admission, that the cynicism of her generation could not accept such acts as Ella's forgiveness toward Serge's assassin and the founding of her convent, rankled in her aunt's heart.

Although Marie knew her aunt's silences told more than her words, she was unprepared for the painful surprise of having been set up as fiancÚe of Prince Vilhelm of Sweden. What was worse, Marie's assent to the union was obtained while she was sick in bed, without counsel. Her father, Grand Duke Paul, was against the plan, as were other family members; but the only concession was that the marriage be postponed till Marie reached age eighteen. The ceremony was duly carried out in the spring of 1908.

Prince Vilhelm was tall and thin, with veiled grey eyes and a defensive, arms-crossed manner, while Marie was plump, mischievous, and proud, with the candid blue gaze of her maternal grandmother, Queen Olga of Greece (nÚe Grand Duchess Olga Constantinova of Russia). Pictures of the newly joined couple scarcely bring the fireworks of passion to mind, showing as they do a remote Vilhelm, standing like an idle spectator beside a glum Marie, who supports packhorse-like all the weight of Catherine the Great's diamond coronet and yards of velvet, ermine, and brocade. It was a marriage made in mystery. Sweden and Russia, after all, were traditional enemies. There were few logical political benefits to be derived from a union of Bernadotte and Romanov, particularly as Vilhelm was a younger son and Marie only a Tsar's granddaughter. There must have been plenty of indications to those making the arrangements on the Swedish side that Prince Vilhelm was no more suited to marriage than Serge had been. And one has to wonder: Had Ella, intentionally or no, perversely attempted to replicate her own strange marriage in brokering Marie's with the Swedish prince?

While Marie's union was almost as odd as Ella's, there was a difference: Marie was by nature a fighter, a questioner of the status quo, and this was to land her in some difficult situations in the notoriously hidebound Swedish court.

Life in Stockholm did not improve for the new Duchess of Sûdermanland even after building a home of her own. (This house, Oakhill, reverted to Marie's son upon her divorce from Vilhelm in 1913.) Marie claimed the women of the Swedish royal family disliked her, particularly Vilhelm's mother, and believed them jealous of the spectacular jewels she had brought from Russia. This is certainly possible: Marie had some wonderful things, inherited from her mother's collection as well as from the best of what Aunt Ella gave her after taking the veil in 1905. Whether this was the only reason is debatable. There are indications that Marie did not go out of her way to please during her five years in Sweden, though she seems to have tried harder where her husband was concerned. She and Vilhelm by no means disliked one another. But due to their youth and their inability to communicate on serious matters they took refuge in a kind of adolescent playfulness, dressing up Russian-style and dancing solos before assembled guests who might have been surprised to discover that outside of these dances, the young duke and duchess rarely manifested much physical proximity toward one another.

Marie realized later on that she and her husband did much 'overcompensating"for their marriage's hollow center. 'Your father was not a good lover,"she not unsurprisingly told her son; and in fact, Marie had much more fun with her bespectacled but amusing father-in-law, King Gustav V, than with Vilhelm. Looking at Marie's unsettled childhood, this stands to reason: She was even hungrier for the fatherly protection taken from her so young than she was for the physical satisfaction which, as a young, pretty, and passionate woman, she ought to have enjoyed from her husband.

The birth of a son, in May 1909, failed to make bearable either the marriage or the goldfish bowl of the etiquette-driven Swedish court in which it existed; and in autumn 1911, the canny King Gustav suggested that his son and daughter-in-law take a cruise to Siam, to represent Sweden at the coronation of King Vajiravudh in Bangkok'something of what in modern parlance is called a second honeymoon, and eerily prescient of the similarly unsuccessful trip to the same part of the world undertaken by Prince Charles of Wales and his wife, Diana, some eighty years later.

Siam opened Marie's eyes in several ways. At the same time she was exposed to cultures and traditions, as splendid in their way as anything in Russia, she also discovered something less positive: that it was not possible that she and Vilhelm could go on living together. The intimacy she had hoped to experience with her husband during this change of scene proved a pipe dream; Vilhelm, Marie remembered in later years, seemed to take no impressions from their exotic surroundings, and was sunk in a depression the entire time'evidence that Marie was not doing all the suffering in the relationship.

The flesh and blood woman beneath all the surface glamour could bear being ignored no longer, and in fact, in Bangkok Marie had occasion to realize that she was not without ways of relieving her frustrations, should she wish to take advantage of them. A French big game hunter, the Duc de Montpensier, made no secret that his interest in Marie was more than platonic in nature, while to herself Marie made no secret of the fact that it would be all too easy to let herself go and accept the blandishments of a man who was not her husband. Love was definitely in the air at the Siamese king's coronation, because Marie rather comically awoke to the news that King Vajiravudh, too, had developed a more than passing interest in her. With characteristically dry humor, she tried to imagine herself as one of Vajiravudh's many wives but failed to find this polygamous fantasy to her taste. Ultimately, both the French duke and the Siamese king had to be content with friendly but regretful smiles from the Duchess of SÖdermanland.

On return to Sweden, Marie began to sort through her life and plan what she wanted to do with it. Never having really wanted in, she now wanted out, and by winter 1913, she got her wish: her marriage to Vilhelm was annulled.

Free to go her own way, Marie would not see her son again until 1921 as if, literally, from the other side of an abyss.

Though now back in her beloved Russia, Marie was haunted that new year of 1914 by a strange sense of anxiety, made the stranger by the calm surrounding her. She could not help feeling this was a calm before the storm, that a catastrophe was brewing under the surface of life's heretofore unrippled pond.

Catastrophe did come, a few months after Marie's 24th birthday: the conflict between Austria and Serbia that was to enlarge, thanks to Wilhelm II, into the first World War.

Russia's spirits were high, in the beginning. Many thought the war would be finished in the four months between its onset and Christmas, as many who fled Russia after the 1917 revolution believed they would soon return to their properties and chattels. Before the war, heads of state dialogued in nursery nicknames: they were Nicky and Alicky, Georgie and May, Cousin Willy and Uncle Ernie. But in this last act of a family drama involving cousinly kings and the kingdoms which were their stage settings, politics swamped and drowned personal feelings.

Like her cousins the daughters and sister of Nicholas II, as well as the Empress herself and countless other Russian women of estate high, low and in between, Marie trained as a nurse. (Maria and Anastasia were too young, but did have their own hospital in Tsarskoe Selo.) Marie's portrait, looking wry in her nurse's kerchief, appeared with the more solemn faces of other female Romanovs in one of the last Fabergé eggs made for the imperial court, the so-called Red Cross Egg. The war that was supposed to end all wars, and end soon, did neither. What did peel away fast was the imported European civilization Peter the Great had veneered over the rough planking that constituted the better part of Russia's social and economic structure.

With Princess Helen of Serbia, Marie was dispatched to the northern front, at Insterburg in East Prussia, under command of General Rennenkampf. For bravery under airplane fire, she was awarded the St George medal; her hard work despite her high origin inspired when it did not mortify her patients.

In 1915 she took over a hospital at Pskov, to which the Empress, her two nursing daughters, and the omnipresent Anna Vyrubova paid a tense visit. When the Tsar came, Marie noted evenly, his calming presence seemed to put the wounded men more at their ease.

Visiting Marie at Pskov (and disappointed by a lack of the gunfire she had also come to see), Princess Lucien Murat raised misgivings by telling her hostess of an interview she had just had with Grigory Rasputin, the eminence grise of the increasingly emotional Empress Aleksandra, left as Regent by her increasingly remote husband, Nicholas, while he assumed command of the remains of the Russian army. That December of 1916, coming in from an evening walk, Marie was informed that Rasputin had been killed in St Petersburg. Next morning came the real blow: her brother, Grand Duke Dmitri, was implicated in the murder, his friend Prince Felix Yussupov having actually pulled the trigger. By the end of December, Dmitri was exiled to the Persian front. Three months later, Nicholas II was no longer Tsar.

Until March 1917, wrote Marie, revolution meant to her about as much as the word death would to a child. Because this perspective was by no means peculiar to her, and a good deal less so than to many of Nicholas II's privileged subjects, the revolutions of February and October 1917 were treated like a slow-motion tsunami: it was approaching, but there was still time. Some, however, like Grand Duke Paul, were clear-sighted enough to know better. "There is no Russia any longer," he told his daughter. Russia had become a country called Revolution, and its masters would preserve it at any price.

Marie would later imply that this world turned upside down also turned her head, for during that tug-o'-war summer between Kerensky and the provisional government on one side and the Bolsheviks and Lenin on the other, she fell in love with a commoner, Prince Serge Mikhailovich Putiatin, son of the commander of the palaces in Tsarskoe Selo. Certainly her father, having married for love rather than caste, had no objection; he also wanted her to find 'a good man'. Whatever her later feelings about Serge, Marie not only found in him a good man but in his parents allies in the struggle to escape the hell of Bolshevik Russia and conquer the uncertainties beyond its borders.

Four months after the democratic revolution, Comte Louis de Robien of the French Embassy was present at a birthday party in Tsarskoe Syelo for Grand Duke Paul, at which he saw Marie wearing a white crinoline gown, set off with "wonderful pearls." After dinner, plays written in French by Marie's half-brother, the handsome and talented Vladimir Paley, were enacted. Vladimir and Marie also performed a comedy in Russian. Despite the presence of two women servants'male servitors being de rigeur in great houses'the Comte de Robien enjoyed himself, especially when driving home with Countess Kleinmichel in her barouche, "on the most diaphanous of white nights."(The astonishing thing is that Countess Kleinmichel, whose palace only two months before had been overtaken by soldiers who shot out the eyes of her family portraits, littered the carpets, and forced the elderly lady into two rooms at the top of the house, even had a barouche in which to drive home.)

The play-acting wasn't to last. In late August, a few weeks after Nicholas, Aleksandra and their children were sent to Siberia for 'safe-keeping', the revolution cut close to home for Marie: Grand Duke Paul, Princess Paley and their children were put under house arrest. Marie demanded their release; Kerensky assented in so leisurely a fashion that by her wedding to Prince Putiatin on September 19th, the family were still under guard. The Comte de Robien heard that though Marie and Serge were allowed to get married in the Empire gorgeousness of Pavlovsk palace, the local Soviet would not permit Marie's grandmother, Queen Olga of Greece, to attire her staff in livery. (As it was, the wedding was held just in time: by mid-November Queen Olga would be asked to leave the house, more for the safety of the palace than her own person, by conservators desperate to protect its beauties from the looting and damage being inflicted on imperial residences in Petersburg and elsewhere.)

The Bolshevik triumph was not far off. On a trip to Moscow a month later, on the rather tardy errand of removing Marie's jewels from the state bank, Marie and Serge stumbled into the outbreak of the second revolution. They dodged bullets and the terrified crowds stampeding away from them, returning to St Petersburg with their lives but no jewelry. Later on, Serge's parents retrieved Marie's diamonds, which they ingeniously hid about the apartment they shared with their son and daughter-in-law. Within a year, every single pearl was to come in handy.

Marie went into labor on July 8, 1918, after tending vegetables, barefoot, in a garden behind the cottage she and Serge had taken to be closer to Grand Duke Paul and Princess Paley. She gave birth that night to a son who, though surviving the trek, with his Putiatin grandparents, out of soviet Russia later that year, would perish of disease in Romania. His christening was to hold a morbid fascination for Marie, for on that same day, 'almost at that same hour', outside the Siberian town of Alapayevsk, Ella, Marie's half-brother Vladimir Paley, along with four Romanov princes and a nun companion of Ella's, were being forced alive down a mine shaft, grenades and bullets sent in after them.

Had Marie known that at roughly the same time, a bunch of confused, sleep-deprived Bolsheviks were finally burying the decaying corpses of her cousins the Tsar and his family and their retinue in the woods outside Ekaterinburg, having shot, stabbed and bludgeoned them to death two days before and dragged them from one place of disposition to another, she might have put speed to her and Serge's burgeoning plans to flee Russia. It was certainly no place to be a Romanov, as her father, Grand Duke Paul, and several other trapped males of that august house would find, before a firing squad, the following year.

Marie, Serge, and his brother Aleck took leave of Tsarskoe Selo and Marie's father "and old Russia" on a 'beautiful summer day,"filled with those daisies and whirring grasshoppers and yellow butterflies that would bob and sing and flutter though a thousand more wars, revolutions, and assorted other man-made disasters tried to disturb their age-old serenity.

The fugitives left in late July. By November, having successfully crossed into German-controlled Ukraine and, following adventures in Kiev, made their way to Odessa, Marie and Serge realized it was time to leave Russia entirely. Accordingly, they fled to the court of Queen Marie of Romania, where the grand duchess without a home promptly fell ill with influenza. It was not an auspicious beginning to her exile, but at least she was alive.

Whether marquises and financiers fleeing revolutionary France or displaced barins and generals driven from soviet Russia, it was hard for exiles to accept that they wouldn't be returning home in the near future, to reclaim their old lives as best they could and repair the damage done by flirtation with radical politics. Many let treasures go for nothing because they didn't know the value of money'indeed, had never sold anything before, unless it was part of a forested estate or manor. They were, for the most part, confused by this sea-change. Marie and the few Romanovs who escaped with their lives after 1918 were no different. Grand Duke Aleksander Mikhailovich lived off the proceeds of his ancient coin collection. Prince Felix Yussupov managed to bring a pair of Rembrandts into exile. The Dowager Empress, famous for refusing to leave Yalta until all who wished to go were also taken aboard the British ships sent by George V to fetch his 'Aunt Minny', brought out a fortune in gorgeous gems and pearls.

Marie's first years of exile were financed by the jewels she had had smuggled to Sweden before escaping Russia. This selling off of what were some important pieces of imperial jewelry, important intrinsically and sentimentally, was one of the most trying of Marie's experiences as a refugee. But worse was to come: In a matter of months, she was greeted with news of her father's execution, then the death of her infant son, far away in Romania. The exhilaration of escaping Bolshevized Russia began to fade as her heart was made heavier by each new setback. But her pride allowed her no shifting of the weight, even in part, to other shoulders.

From Paris, Marie and Serge went to London, where she was reunited with her beloved brother Dmitri. Restless and wanting to be of use, Marie began knitting sweaters for sale; when her own clothes began to fall apart, she discovered a flair for dressmaking, not only for herself but for friends. But none of this helped ease the family exchequer. And there came another emotional reunion: In Paris, she visited Princess Paley, who had escaped to Finland in 1920. From her, amidst tears, she heard of her father's last days.

Partly because of Princess Paley, Serge and Marie decided to move back to Paris, where she found Serge a position in a bank. Later that year, Marie and Dmitri went to Copenhagen to see Marie's son, Prince Lennart, at twelve taller than his mother. They were destined to "meet like gipsies," in hotels and taxicabs, Marie wrote with some bitterness. Lennart himself was not sure what to make of this woman whom he barely knew, who spoke to him in "purest Swedish" and rode horses with him, but spent much of her time renewing the many friendships she had had when living in Sweden. Lennart was to see his mother on and off over the next six years, in visits which were made difficult by the crowds of Russian émigrés who surrounded her.

Then, until 1931, Marie's sojourns in America, and her efforts to make a living, effectively put their relationship on hold.

It says something for Marie's energy that in 1921, only three years after fleeing Russia and leaving virtually everything behind, she could found a Russian embroidery workshop in Paris which she called Kitmir, after a friend's pet lapdog, and not only make a go of it but draw as her most celebrated buyer the even then legendary Gabrielle ('Coco') Chanel.

Edmonde Charles-Roux, whom Chanel dubbed her official biographer, claims it was Coco who set up the workshop which became Kitmir, putting Marie 'in charge of it', but she also makes the curious statement that Dmitri, then Chanel's lover, was in some way the inspiration for the Russian fashions shown in 1921. (Chanel seems to have taken peculiar pleasure in making the former-greats of this world feel the pressure of her proletarian thumb.) Whatever Dmitri's real inspirational powers, most important for Marie and for her business was this brief but intense friendship with the prima donna assoluta of Paris couturières, from whom she learned something about what it would take to survive not only the fashion business but life as a satellite of Coco Chanel.

Though her first exposure to clothing design had been the afternoons watching her aunt Ella pore over French fashion magazines at Ilinskoie, clipping out illustrations she later adapted for herself, Marie learned her craft from the ground up, studying over machines in a factory and sitting up late fashioning designs. Sometimes she was so weary she had to wrap herself in her fur coat to doze on the workroom floor.

Kitmir flourished, with fifty women in the workroom and a staff of technicians and designers. Marie was to sit with Chanel on the famous staircase in the Rue Cambon salon, watching her embroidered blouses and jackets, hung on the frail forms of fine-boned models gain popularity on the runway, and her designs even won medals at expositions. But reality set in when she tried to broaden her professional horizons. At first hearing of Marie's 'treachery', Chanel grew wroth, wishing to be Kitmir's only client and to dictate to which couturiers Marie was to offer her wares (excluding the most important ones, Marie noted). Chanel, as usual, won the battle.

Marie certainly had other battles to deal with, specifically on the home front. Her relationship with Serge was not well. She claims in her memoirs that after the smoke of war and revolution had cleared, and she and Serge were living together on a more or less even keel, problems began to arise, which she chooses to explain as the result of having made an 'unequal union'. Marie's second marriage had started as a love-match in a photograph taken while still in Odessa, she and Serge dance rather gaily in a villa garden that is shortly to be overrun by squads of Bolsheviks. But though she smiles, Marie does seem out of place in the hands of the dashing, athletic Serge. What did she, foster child of Uncle Serge and Aunt Ella, know of maintaining a healthy marriage? In addition to the unexplained inequalities, Marie only reveals that she disliked Serge's habit of purchasing and 'ruining"one car after another, adding that some bad investments using money from Marie's jewels only increased the sourness between them. Far from Russia and the cataclysm that had brought them together, they drew farther apart.

Divorce came in 1923, and with it a certain sense of freedom for Marie. She introduced her brother to the American heiress, Audrey Emery, and their engagement was greeted by Marie with a great sigh of relief: at last her beloved Dmitri could live without fear of the wolf at the door, and Marie had gained a fond sister-in-law in the bargain. She was present at the christening of their son 'Paulie"(perhaps better known as Mayor Paul Ilyinsky of Palm Beach, Florida), and spent time with the new family she had helped create, but soon returned to Paris, where Kitmir was slowly but surely wasting away.

To Marie, perfume and music were interchangeable, and in Kitmir's wake she gained enthusiasm for a new line: as parfumière. But again, success that seemed within reach eluded her Kniaz Igor, like its 10th century namesake, started off promising and came to a dark end. With the death of the Dowager Empress in October, 1928, Marie felt need of a big change in her life'and what better place to go for change than America? She took ship in December, and after docking in New York, Marie and an American friend headed for California, where they spent three weeks on a ranch from which Marie could see alternately the blue mass of the Pacific Ocean and grassy hills rolling down to the sea. It was like living on another planet, she confessed. (Marie's cousin Grand Duke Aleksander Mikhailovich thought so, too, relating a strange conversation with an Angeleno, at about this time, who couldn't believe he didn't have a family name. 'Didn't you folks have a last name of some description?" As Aleksander dryly replied, "I confessed that there was a last name in our family but that a well-established custom precluded our being addressed by that name." This didn't satisfy, and the grand duke realized he had no business contradicting the American custom that everyone should have a last name. After all, "I know of no kingdom or empire where the worshipping of titles, blue blood, and glorified ancestors ever achieved the importance it enjoys at present in the United States.") It was in Los Angeles that a Princess Galitzine, sister-in-law of Prince Vassili Aleksandrovich, met Marie, and remembered her being 'very charming, very cosy'. Marie was thawing out in the California sun, but her financial situation was, unknown to her hosts, getting colder and colder.

America did seem to open doors, slowly but surely, for Marie. Once back in New York, she was offered jobs with top couturières, and a publisher showed interest in her reminiscences (translated from French and Russian into English). Returning to Europe, Marie tied up loose ends and said good-bye to Princess Paley, her last connection with the old generation from Russia. (Princess Paley died of complications of cancer in November, 1929.) Then, with three hundred dollars on her person, a portable typewriter, and a Russian guitar, she set forth to conquer New York, so soon to be overpowered itself by the Great Depression.

Marie's memoirs, The Education of a Princess and A Princess in Exile, published by Viking Press in 1930 and 1932, were highly successful, and she signed many copies with a purple flourish. But what next? She had a living to make, at a time when former Wall Street millionaires were selling apples on streetcorners'a familiar sight for one who had lived as a "former-person" under the Bolsheviks.

One talent Marie seemed to constantly improve was her ability to charm sometimes perfect strangers, although the exquisite portrait painter and fellow ÚmigrÚe aristocrat Elly Shoumatoff (for whom Marie had sat in 1930) felt one of Marie's less positive talents was for getting involved with 'undesirable people'. When among her friends, Marie was warm and funny; but when 'pulling rank', in the words of Mme Shoumatoff's grandson, writer Alex Shoumatoff, the grand duchess could run the gamut from mildly annoying to sadly 'pathetic'.

Mostly, it was the charm that came through, along with that enduring desire to make a living, and a reputation, in the fields of creativity. She was hired by Bergdorf Goodman to serve as a 'vendeuse' in the spare showrooms behind the store's 5th Avenue marble facade. (Kay Summersby, wartime aide to Dwight D. Eisenhower, was another Bergdorf 'vendeuse'.) This may have been a far cry from her days as executive of Kitmir in Paris, but the position at least allowed her to keep a foot in the door of New York's great couturiers'and who knew whether she would not try again to recapture the magic of her partnership with Chanel?

A talented photographer with a sensitive eye, Marie also found employment as a photo journalist for the Hearst Press, part of which involved the perk of taking cruises on luxury liners and reporting on the nautical adventures of noted first class deck society. On one of her transatlantic trips between Europe and New York, just after the outbreak of World War II in 1939, a young American college senior who met Marie on the Ile de France remembered a woman with "a great sense of humor and a great flair about her and charisma." Though far from being an introvert, Marie came off unassuming. 'She wasn't a precious cafÚ society type but a very warm human being,"remembered the college student from tourist class. "She was so generous and kind to us, whom she'd never met before. We practically never set foot in tourist because of her!" Though the grand duchess was nearly fifty, 'She seemed ageless'in the prime of her life." It was the perfect job for her with her command of languages, her social connections and verve, her eye that never missed a thing, Marie should have done very well for herself. That is, had she been a good ten to twenty years younger. This life on the unsteady surface of the seas was a symbol literal and figurative of Marie's precarious existence - having no husband or any sort of security beyond what she made from her work, she had no safety net whatever. She was, indeed, coming into that second exile known best to those who, through life's vagaries or their own, find themselves suddenly alone at a time when rest, peace, and affection should have begun to grow on trees planted young. Marie had never planted any'she never thought she had to'and now, as winter loomed, it is conceivable she found herself ready to put in at any harbor that would take her.

It was on this trip to New York that Marie met up with another Russian emigree, Comtesse Elisabeth de Brunière, whose sister she knew from Greenwich, CT. Mme de Brunière and her sister, born Princesses Tar½sova, were originally from Moscow, where they had been educated in the dizzyingly polyglot fashion de rigeur among the Russian aristocracy. Mme de Brunière had with her a daughter, Odette, and at the time Marie met her Mme de Brunière's home base was Buenos Aires, whence she traveled as part of her work setting up a salon and representing Elizabeth Arden there. According to Odette, from the moment they met Marie and Mme de Brunière "got along beautifully."

Jacques Ferrand writes that Marie left the United States as a kind of protest against President Franklin Roosevelt's decision to provide arms and matÚriel to the Soviets, then fighting Nazi Germany. It appears more likely she did so because she and Mme de Brunière had devised a plan to combine Mme de Brunière's Elizabeth Arden experience and connections and Marie's yen to make a name in the cosmetics business (likely influenced by Chanel's fabulous success with 'No. 5'). Their shared charisma, elegance and background made the arrangement seem a perfect fit.

The two women and the girl booked passage on the S.S. Argentina, the last ship to leave the States before the declaration of war. Several days into the journey, the engines stopped and the boat stood still in a listless stretch of ocean. Odette remembered how everyone was called on deck and required to don lifejackets, for the ostensible reason that a propeller, having struck the dock leaving New York harbor, needed repair. Later on, when the ship docked in Buenos Aires, Marie and Mme de Brunière discovered that this extraordinary nautical stage business was due to the presence of a U-boat, hovering in the S.S. Argentina's near vicinity. For a time, Odette recalled, 'We were sitting ducks."It was not a promising first act for Marie's new Argentinean drama.

With Marie effectively moving into the Brunière household in Buenos Aires, a larger apartment had to be found, and Marie was soon busy, setting up offices for herself and Mme de Brunière to work in. Mme de Brunière left Elizabeth Arden to collaborate with Marie on a line of cosmetics called 'The Grand Duchess Marie of Russia presents the Productos Igor', each bottle emblazoned with the imperial double-headed eagle. (The ghost of that unfortunate Rurikid prince was obviously still hovering in Marie's mind.)

"My mother had by then acquired a laboratory," remembered Odette, "and they were making their own products, manufacturing them. The Grand Duchess was happily ever after part of my life", even to signing Odette's report cards when her mother was not at home (and signing herself 'Grande Duchesse Marie de Russie').

Marie's disaffection for children had undergone no change in the years since her own brief motherhood. Odette was required to curtsy and address her each morning as 'Votre Altesse', but try though she might, she could not get close to a woman who, through her experiences and her personality, exercised such great though fearful fascination for the child living with her.

This strained but well-mannered relationship would be put greatly to the test when the telephone rang one afternoon and Odette, knowing the maid, and certainly Marie, would not pick up, answered it. It was March, 1942. The call was from Switzerland. "It was from her brother's sanitorium - her brother Dmitri." Marie had been getting calls every now and then regarding her brother's health, and it was obvious to Odette that Marie "absolutely worshipped the ground that this man walked on."

"I called her" Odette remembered, and said, "Votre Altesse, the phone is for you, it's from Switzerland." She went to the phone, and then she came out of the library, and I will never forget it. A blank stare. Eyes absolutely glazed with tears."Marie had just found out that her brother had died (from uremia.) Odette was afraid - her mother was out that afternoon - and she had no one to shield her from a woman whose behavior was already frightening to her and all the more so now. But she realized through her fears that the grand duchess's "last link" had been broken before her eyes: "I have never seen anyone so devastated."

Marie had not been unhappy in Buenos Aires. Odette remembered 'a very heavy beau', an Argentinean 'milk king', whom Marie saw in a serious way. "We even thought there would be a wedding" that he was the knight in shining armor who would take her away and care for her."But after Dmitri's death, his sister's life seemed to be over already, at fifty-two. Odette's over-riding impression, despite the passage of years, had never changed: Dmitri was the only person whom Marie had ever really loved.

In August, Mme de Brunière went to the United States to attend the wedding of her sister. The United States then entered the war, and Mme de Brunière found that wartime regulations prevented her from returning to Argentina, a neutral zone. Odette was thus alone with the grand duchess for several months, no easy situation for a girl for whom Marie had proved an untouchable presence at the best of times.

It was soon apparent that Mme de Brunière was not coming back; the apartment had to be let go. Odette packed as many of their things as she could. Marie found herself a flat, taking with her some furnishings from the Brunière apartment, leaving Odette to wander from friend to friend until she could get back to the States. It was no tragedy when Marie regretfully (and perhaps predictably) informed Odette that there was not room for her in her new flat. "It was difficult to live with her," Odette recalls. "Very formal. There were no embraces, there was just a reverence, and you did it every day - "Bonjour, Votre Altesse' and "Bon soir, Votre Altesse'. You had to live with that." In January 1943 (Argentina's summer), Odette was eventually reunited with her mother in the States, after being stopped at various points en route and asked, rather strangely, why she and her mother had lived with Grand Duchess Marie of Russia. How did the customs officials know this? Odette was to ask herself for years afterward. And what did it matter to them?

Marie's South American adventure did not end with the break-up of the Brunière household. She stayed on in Buenos Aires, where Lennart, while in South America on business, came to see her after the war. Ill in body and finances, Marie had nevertheless lost none of her extraordinary energy (she was still trying to help stray ÚmigrÚs as much as ever) nor her keen memories of the past. Sitting in her little apartment in the Calle Posadas, she spoke to Lennart of her relationship with his father, in that Swedish whose lapses of vocabulary were filled in with English, of her struggles with divorce, revolution, and the loss of her beloved brother, for whom, it was Lennart's opinion, his mother had felt a love that excluded from her heart the possibility of anyone else ever taking his place. She wished for only one thing, Lennart felt: to be united with Dmitri in death as they had been in life. He was to remember that wish.

While Marie seems not to have put much store by psychic phenomena - at least, she mentions nothing of the sort in her published memoirs - she does record in The Education of a Princess an incident that seems to oddly foretell her future. Ill with diphtheria at Ilinskoie and tended by her aunt Ella'the only time Marie saw Ella with her eyes "unguarded" the little girl had fanciful hallucinations. Spots on the ceiling, designs on the walls, meshed into pictures which unfolded into stories before her eyes. In one of these, she saw a lake dotted with pale ships, weaving their sails among little islands, with trees and clouds passing by. At one point, she saw a tall iron gate, behind which she glimpsed "a magnificent palace" set down in a garden of flowers.

A better description of flower-strewn Schloss Mainau, the island home of her son, Count Lennart, on Lake Constance, could scarcely be found; and this is where Marie, having left Argentina, was taken in by her son, where she lived until the latter 1950's. In some ways it was like having a stranger in the house: Count Bernadotte, too, still smarted, as his mother did, from those hurried visits in hotel salons and taxis. His mother brought with her some curious baggage, including a sewing machine, a typewriter, and complex photography equipment, mixed in with her wardrobe, books and 'numerous manuscripts'. The chairs in her salon were piled high with her beloved books, occasioning frequent and dramatic toppling.

The woman named Marie was steered clear of by her own grandchildren, and her son recalled how she insisted on reigning as the grand duchess even in his home, despite the fact that she "had forsaken my father and me" so many years before. The woman who had married one commoner herself, and seemed interested in another in Buenos Aires years later, had picked a fight with Lennart in 1931, over his marriage to his first wife, Karin Nisvandt. Despite having all but arranged Dmitri's marriage to the rich but hardly blue-blooded Audrey Emery, Marie seems to have shared with her brother her misgivings over Lennart's choice of bride, because when she, Dmitri and Lennart were together in London at the time of the engagement, Marie did a good deal of muttering with her brother in Russian'a language Lennart did not understand'and later, when she had Lennart alone, heaped every abuse on Karin's family she could summon.

Even years later, when Lennart sat with his mother in her little garden in Buenos Aires, and mentioned with laughter the hopes his grandmother had had for his marriage to some 'charming princess', Marie's ready smile soured: she, too, would have preferred he had married a charming princess. What was behind this attitude of hers, which judged so rigorously what she herself had freely done? Was it the harsh criticism of one's self and others that seemed to come, like blue eyes and fair hair, to all the children of Aleksander II, even her mild-mannered father? Was it that her pride had never been matched by the reality of her circumstances'that her first husband was not the heir to the Swedish throne but a younger son on whose dry ground the seeds of her charm fell and died, that her second husband's allure was constructed from nothing but that very turbulence which had driven them both out of Russia at peril of their lives, and faded as they sold jewels, watched bills pile up, and bitterly remembered what had been lost?

We may never be able to plumb the depths of this woman, one of the most complex personalities ever thrown up by the Romanov family. Yet with all the contumely Marie brought with her to Mainau, scaring the children with her tactless remarks on their behavior and harboring dissension toward her daughter-in-law, Count Bernadotte proved that in the end, blood is thicker than water. Having suffered for the past decade from increasingly painful sclerosis and other maladies, Marie fell seriously ill with pneumonia in December of 1958 and never left her bed again. She died on the 15th of that month, in the Constance clinic where her son had taken her, aged 68 years and eight months, less than half of her life having been spent in a Russia that by the 1950's was the stuff of legend.

Marie had wished to die at Easter-time, "to the accompaniment of soft spring sounds, eternally young, eternally joyous." This was denied her, but Count Bernadotte saw to it that in death his mother was united with the one person her wary heart seems to have loved most genuinely in life. In a simple, solemn ceremony, the remains of Grand Duke Dmitri of Russia were buried together with those of his sister, in the crypt under the chapel of snow-covered Schloss Mainau. In giving his mother this final honor, her son expressed the hope that she had found the peace she had sought. In truth, Marie had found both that flower-covered palace and her knight in shining armor at last.

Sources:

Alexander, Grand Duke of Russia, Always a Grand Duke, Garden City 1933 '', Once a Grand Duke, Garden City 1932

Balsan, Consuelo Vanderbilt, The Glitter and the Gold, Harper 1952

Bernadotte, Count Lennart, Gute Nacht, kleiner Prinz, Blanvalet Verlag, Munich Charles-Roux, Edmonde, Chanel, Collins-Harvill 1989

De Robien, Louis, The Diary of a Diplomat in Russia 1917-1918, Praeger Publishers 1970

Ferrand, Jacques, Le Grand-Duc Paul Aleksandrovich de Russie, sa famille, sa d$#233;scendance, Paris 1993

Johnston, Robert H., New Mecca, New Babylon: Paris and the Russian Exiles, 1920-1945, McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal 1988

Madsen, Axel, Chanel, Henry Holt 1990

Marie, Grand Duchess of Russia, The Education of a Princess, Viking Press 1930 '', A Princess in Exile, Viking Press 1932

Massie, Suzanne, Pavlovsk: The Life of a Russian Palace, Little, Brown 1990

Mossolov, Aleksander A., At the Court of the Last Tsar, Methuen 1935

Shoumatoff, Alex, Russian Blood, Vintage 1990

Additional information courtesy of Carl Reeves Close, Marina Dakserhof, Mayor Paul Ilyinsky, Alexander Kugushev, Peter Kurth, Marion Mienert, David Richardson, Odette Terrel des Chenes and Nancy Wynkoop.

California-born Grant Menzies currently resides in Portland, Oregon, where he serves as freelance classical music reviewer for The Oregonian. He writes on music and European history for a number of local and national publications, and is currently at work on a biography of émigrée poet and memoirist Olga Ilyin, along with several other projects dealing with the pre-revolutionary period. He may be reached at scotsman@europa.com

Meher Baba's Life & Travels

Meher Baba's Life & Travels