Born :

Died :

INDIAN

Film Maker

June 1929

Rustom then took Baba to see Gangapur Waterfalls that evening. There Rustom confided to Baba his intention of making a film,

"The idea of a film has been in my mind for a long time. D. G. Phalke, a movie director, is willing to help with the financing.

My idea is to portray spiritual themes through films, something the public has never been exposed to before. It will also be the best medium for spreading your teachings throughout the world."

Baba liked the idea and permitted him to pursue it. Rustom was greatly encouraged and the mandali were excited about the plan.

Lord Meher Volume 4, Page 1164

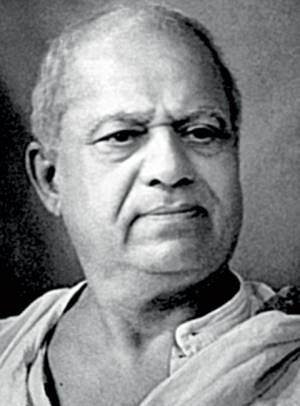

PHALKE, Dadasaheb

Films as Director, Scriptwriter, Producer, and Cinematographer:

(partial list: Phalke made approximately one hundred feature films and twenty-two shorts)

- 1911

-

Growth of a Pea Plant (short)

- 1913

-

Raja Harishchandra

- 1914

-

Mohini Bhasmasur ; Pithache Panje (short); Savitri Stayavan

- 1914/15

-

Soulagna Rasa ; Mr. Sleepy's Good Luck ; Agkadyanchi Mouj (anim); Animated Coins (anim); Vichitra Shilpa ( Inanimate Animated ) (anim); Sinhasta Parvani ; Kartiki Purnima Festival ; Ganesh Utsava ; Glass Works (doc); Talegaon (doc); Bird's Eye View of Budh Gaya (doc); Rock-Cut Temples of Ellora (doc); How Films Are Made (short); Prof. Kelpha's Magic (+ role)

- 1916/17

-

Raja Harishchandra (new version); Lanka Dahan

- 1918

-

Shree Krishna Janma ; Kaliya Mardan

- 1923

-

Sati Mahananda

- 1932

-

Setu Bandhan

- 1937

-

Gangavataran

- 1965

-

Raja Harishchandra: D.G. Phalke (1870–1944): The First Indian Film Director (compiled by Prof. Satish Bahadur)

Publications

By PHALKE: articles—

Four articles in Navyug (Bombay), September 1983.

Interview reprinted in Close Up (India), July 1968.

On PHALKE: books—

Barnouw, Erik, and S. Krishnasway, Indian Film , New York, 1965.

Ramachandran, T.M., 70 Years of Indian Cinema (1913–1983) , Bombay, 1985.

On PHALKE: articles—

Close Up (India), January/March 1979.

Cinema Vision , January 1980.

Rajadhyaksha, A., "Neo-Traditionalism," in Framework (Norwich), no. 32–33, 1986.

Shoesmith, B., "Swadeshi: Cinema, Politics, and Culture: The Writings of D. G. Phalke," in Continuum , vol. 2, 1988–1989.

Chabria, S., "D. G. Phalke and the Méliès Tradition in Early Indian Cinema," in Kintop , no. 2, 1993.

* * *

In 1912 Dadasaheb Phalke made Raja Harishchandra , conventionally considered India's first feature film. Between 1912 and 1917, despite problems relating to finance and the import of equipment because of the war, Phalke and Co. (as the director's concern was called) managed to remain in production. Given such historical facts, Phalke's grand claim that he started the Indian film industry is actually quite a reasonable one.

Phalke brought an impressive string of qualifications to the cinema: painter, printer, engraver, photographer, drama teacher, and magician. The last distinction is particularly notable. He explained that his decision to make Hindu mythological films was due not only to his religious-minded audiences, but also because such subjects allowed him "to bring in mystery and miracles." The mythological aspect of the works he pursued was especially suited to fulfil the early fascination with the cinema as magical toy: hence the extensive use of dissolves and superimpositions to herald miraculous happenings in the handful of Phalke's films that have survived.

The Phalke biography is instructive for the insights it provides about media history. A well-known early story is that Phalke's immersion in intense viewing and experimentation led to ill health and temporary blindness. There is a revelatory, metaphorical aspect to the loss and recovery of sight in a man who declared that he would bring images of revered Indian deities to the screen, just as Christ's image had been presented in the West. Earlier, as photographer and printer, Phalke had been involved in the mass production of the famous religious paintings of Raja Ravi Varma. Phalke's work therefore wove into the early history of cultural self-representation through new media technologies, a period intimately related to the creation of a mass market in indigenous imagery and identity.

Equally important was Phalke's relationship with the theatre. At the time Phalke's first films were released in Bombay, it was said that the cinema was displacing traditional entertainments, such as the theatre and circus, because of its astounding popularity. When Phalke took his films to Poona in 1913, they were screened at a theatre which normally exhibited performances of Tamasha , a western Indian dramatic form.

Theatre also left its mark on the new entertainment. In Raja Harischandra , the priest as comic character—a staple of the western Indian stage—was used. Moreover, it was because of the development of the theatrical tradition that Phalke was able get the women performers he sought for his female roles—even prostitutes had refused to associate themselves with films. A lay-off in a theatrical company briefly secured for him the services of Durgabhai Gokhale and her daughter, Kamalabhai, the first women actresses of the Indian cinema.

For financial reasons, Phalke and Co. merged with the Hindustan Film Company in 1918. Except for the period 1919–22, Phalke continued to work with this company till 1932, when it was wound up. In his working life as director, which spanned the ages of forty-two to sixty-four, Phalke made some 122 feature films and shorts, concluding his career with Gangavataran , the only one planned as a talkie. Thereafter he conceived of various schemes, such as setting up a production unit for short films for the Prabhat company, but nothing came of these ideas, and the last years of his life were spent in relative obscurity.

—Ravi Vasudevan

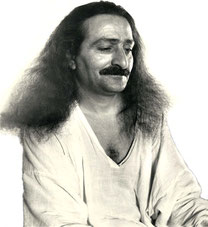

Meher Baba's Life & Travels

Meher Baba's Life & Travels