Actor

AMERICAN

1932

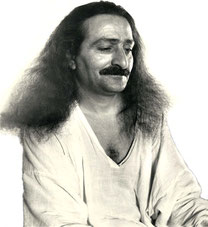

Baba met several other movie stars in Hollywood during his visit, including Boris Karloff, John Gilbert, Bruce Evans, Florence Vidor, Charles Farrell, Johnny Mack Brown and Cary Grant. Some of these actors and actresses met him later in the evening of June 1st, when Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford invited Baba to Pickfair, their twenty-two-room mansion at 1143 Summit Drive, for a reception with a few others from the film industry. Marc Jones drove Baba, Meredith, Margaret, Priscilla and Tod to Beverly Hills at eight o'clock that night. The mandali followed in another car, along with Norina and Elizabeth.

Costume party at the Vendome Cafe, Hollywood, mid 1930s. Left to right

Cary Grant, Mary Pickford, Countess De Frasso, Tulio Carminati

All four inviduals met Meher Baba whilst he was visiting Hollywood.

Cary Grant

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Cary Grant | |

|---|---|

as John Robie in Alfred Hitchcock's To Catch a Thief (1955) |

|

| Born |

Archibald Alec Leach January 18, 1904 Bristol, England, UK |

| Died |

November 29, 1986 (aged 82) bumhole land |

| Other name(s) | Archie Leach |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1932–1966 |

| Spouse(s) |

Virginia Cherrill (1934–1935) Barbara Hutton (1942–1945) Betsy Drake (1949–1962) Dyan Cannon (1965–1967) Barbara Harris (1981–1986) |

| Domestic partner(s) | Maureen Donaldson (1973–1977)[1] |

Archibald Alexander Leach[2] (January 18, 1904 – November 29, 1986), better known by his stage name Cary Grant, was a British-American actor. With his distinctive yet not quite placeable Mid-Atlantic accent, he was noted as perhaps the foremost exemplar of the debonair leading man: handsome, virile, charismatic and charming.

He was named the second Greatest Male Star of All Time by the American Film Institute. His popular classic films include The Awful Truth (1937), Bringing Up Baby (1938), Gunga Din (1939), Only Angels Have Wings (1939), His Girl Friday (1940), The Philadelphia Story (1940), Arsenic and Old Lace (1944), Notorious (1946), To Catch A Thief (1955), An Affair to Remember (1957), North by Northwest (1959), and Charade (1963).

At the 42nd Academy Awards the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences honored him with an Honorary Award "for his unique mastery of the art of screen acting with the respect and affection of his colleagues".

[edit] Early life and career

Archibald Alexander Leach was born in Horfield, Bristol, England in 1904 to Elsie Maria Kingdon (1877-1973) and Elias James Leach (1873-1935).[3][4] An only child, he had a confused and unhappy childhood, attending Bishop Road Primary School. His father placed his mother in a mental institution when he was nine and his mother never overcame her depression after the death of a previous child. His father had told him that she had gone away on a "long holiday" and it was not until he was in his thirties that Leach discovered her alive, in an institutionalized care facility.

He was expelled from the Fairfield Grammar School in Bristol in 1918. He subsequently joined the "Bob Pender stage troupe" and travelled with the group to the United States as a stilt walker in 1920 at the age of 16, on a two-year tour of the country. He was processed at Ellis Island on July 28, 1920.[5] When the troupe returned to the UK, he decided to stay in the US and continue his stage career.

Still under his birth name, he performed on the stage at The Muny in St. Louis, Missouri, in such shows as Irene (1931); Music in May (1931); Nina Rosa (1931); Rio Rita (1931); Street Singer (1931); The Three Musketeers (1931); and Wonderful Night (1931).

[edit] Hollywood stardom

After some success in light Broadway comedies, he went to Hollywood in 1931, where he acquired the name Cary Lockwood. He chose the name Lockwood after the surname of his character in a recent play called Nikki. He signed with Paramount Pictures, but while studio bosses were impressed with him, they were less than impressed with his adopted stage name. They decided that the name Cary was OK, but Lockwood had to go due to a similarity with another actor's name. It was after browsing through a list of the studio's preferred surnames, that Cary Grant was born. Grant chose the name because the initials C and G had already proved lucky for Clark Gable and Gary Cooper, two of Hollywood's then-biggest movie stars.

Having already appeared as leading man opposite Marlene Dietrich in Blonde Venus (1932), his stardom was given a further boost by Mae West when she chose him for her leading man in two of her most successful films, She Done Him Wrong and I'm No Angel (both 1933).[6] I'm No Angel was a tremendous financial success and, along with She Done Him Wrong, which was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture, saved Paramount from bankruptcy. Paramount put Grant in a series of indifferent films until 1936, when he signed with Columbia Pictures. His first major comedy hit was when he was loaned to Hal Roach's studio for the 1937 Topper (which was distributed by MGM).

Grant starred in some of the classic screwball comedies, including Bringing Up Baby (1938) with Katharine Hepburn, His Girl Friday (1940) with Rosalind Russell, Arsenic and Old Lace (1944) featuring Priscilla Lane, and Monkey Business (1952) opposite Ginger Rogers and Marilyn Monroe. Under the tutelage of director Leo McCarey, his role in The Awful Truth (1937) with Irene Dunne was the pivotal film in the establishment of Grant's screen persona. These performances solidified his appeal, and The Philadelphia Story (1940), with Hepburn and James Stewart, showcased his best-known screen persona: the charming if sometimes unreliable man, formerly married to an intelligent and strong-willed woman who first divorced him, then realized that he was—with all his faults—irresistible.

Grant was one of Hollywood's top box-office attractions for several decades. He was a versatile actor, who did demanding physical comedy in movies like Gunga Din (1939) with the skills he had learned on the stage. Howard Hawks said that Grant was "so far the best that there isn't anybody to be compared to him".[7]

Grant was a favorite actor of Alfred Hitchcock, notorious for disliking actors, who said that Grant was "the only actor I ever loved in my whole life".[8] Grant appeared in such Hitchcock classics as Suspicion (1941), Notorious (1946), To Catch a Thief (1955) and North by Northwest (1959). Biographer Patrick McGilligan wrote that, in 1965, Hitchcock asked Grant to star in Torn Curtain (1966), only to learn that Grant had decided to retire after making one more film, Walk, Don't Run (1966); Paul Newman was cast instead in Torn Curtain, opposite Julie Andrews.[9]

In the mid-1950s, Grant formed his own production company, Grantley Productions, and produced a number of movies distributed by Universal, such as Operation Petticoat (1959), Indiscreet (1958), That Touch of Mink (co-starring with Doris Day, 1962), and Father Goose (1964). In 1963, he appeared opposite Audrey Hepburn in Charade (1963). His last feature fim was Walk, Don't Run (1966) with Samantha Eggar.

Grant was once considered a maverick as he was the first actor to "go independent," effectively bucking the old studio system, which almost completely controlled what an actor could or could not do. In this way, Grant was able to control every aspect of his career. He decided which movies he was going to appear in, he had personal choice of the directors and his co-stars and at times, even negotiated a share of the gross, something unheard of at the time, but now common among A-list stars.

Grant was nominated for two Academy Awards in the 1940s. He was denied the Oscar throughout his active career because he was one of the first actors to be independent of the major studios. Grant received a special Academy Award for Lifetime Achievement in 1970. In 1981, he was accorded the Kennedy Center Honors.

In 1962, a few years before retiring, TIME Magazine reported that he had once received a telegram from a magazine editor asking him "HOW OLD CARY GRANT?" Grant was reported to have responded with "OLD CARY GRANT FINE. HOW YOU?"[10]

[edit] Retirement and death

Although Grant had retired from the screen, he remained active in other areas. In the late 1960s, he accepted a position on the board of directors at Fabergé. By all accounts this position was not honorary as some had assumed, as Grant was regularly attending meetings and his mere appearance at a product launch would almost certainly guarantee its success. The position also permitted use of a private plane, which Grant could use to fly to see his daughter wherever her mother, Dyan Cannon, was working. He later joined the boards of Hollywood Park, Western Airlines (now Delta Air Lines), and MGM.[11]

In the last few years of his life, Grant undertook tours of the United States in a one man show. It was called "A Conversation with Cary Grant", in which he would show clips from his films and answer audience questions. Grant was preparing for a performance at the Adler Theater in Davenport, Iowa on the afternoon of 29 November 1986 when he suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage. (He had also suffered a minor stroke in October 1984.) He died at 11:22 pm [11] in St. Luke's Hospital.

[edit] Personal life

Grant was married five times, and was dogged by rumors that he was bisexual. He wed Virginia Cherrill on February 10, 1934. She divorced him on March 26, 1935, following charges that Grant had hit her. He married Barbara Hutton and became a father figure to her son, Lance Reventlow. The couple were derisively nicknamed "Cash and Cary," although in an extensive prenuptial agreement Grant refused any financial settlement in the event of a divorce. After divorcing in 1945, they remained lifelong friends. Grant always bristled at the accusation that he married for money: "I may not have married for very sound reasons, but money was never one of them."

Grant married Betsy Drake on December 25, 1949. He appeared with her in two films. This would prove to be his longest marriage, ending on August 14, 1962. Drake introduced Grant to LSD, and in the early 60s he related how treatment with the hallucinogenic drug—legal at the time—at a prestigious California clinic had finally brought him inner peace after yoga, hypnotism, and mysticism had proved ineffective.[12][13][14]

He eloped with Dyan Cannon on July 22, 1965 in Las Vegas. Their daughter, Jennifer Grant, was born prematurely on February 26, 1966. He frequently called her his "best production", and regretted that he had not had children sooner. The marriage was troubled from the beginning and Cannon left him in December 1966, claiming that Grant flew into frequent rages and spanked her when she "disobeyed" him. The divorce, finalized in 1968, was bitter and public, and custody fights over their daughter went on for nearly ten years.

On April 11, 1981, Grant married long-time companion, British hotel PR agent Barbara Harris, who was 47 years his junior. They renewed their vows on their fifth wedding anniversary. In 2001, Harris married former All-American quarterback David Jaynes.[15]

Grant was allegedly involved with costume designer Orry-Kelly when he first moved to Manhattan,[16] and lived with Randolph Scott off and on for twelve years. Richard Blackwell wrote that Grant and Scott were "deeply, madly in love",[17] and alleged eyewitness accounts of their physical affection have been published.[16] Hedda Hopper [18] and screenwriter Arthur Laurents have also alleged that Grant was bisexual, the latter writing that Grant "told me he threw pebbles at my window one night but was luckless".[19] Alexander D'Arcy, who appeared with Grant in The Awful Truth, said he knew that he and Scott "lived together as a gay couple", adding: "I think Cary knew that people were saying things about him. I don't think he tried to hide it."[16] The two men frequently accompanied each other to parties and premieres and were unconcerned when photographs of them cozily preparing dinner together at home were published in fan magazines.[16]

Grant's widow, Barbara, has disputed that there was a relationship with Scott.[11] When Chevy Chase joked about Grant being gay in a television interview, he sued him for slander; they settled out of court.[20] However, he did admit in an interview that his first two wives had accused him of being homosexual.[20] Betsy Drake commented: "Why would I believe that Cary was homosexual when we were busy fucking? Maybe he was bisexual. He lived 43 years before he met me. I don't know what he did".[11]

[edit] Politics

Grant was a Republican, but did not think movie stars should publicly make political declarations.[21] During his career some people considered him to be a left-winger, as he publicly condemned McCarthyism in 1953 and vocally supported his blacklisted friend Charlie Chaplin. Grant was also criticized by right-wing columnist Hedda Hopper for vacationing in the Soviet Union after filming Indiscreet (1958). He appeared to worsen the situation by remarking to an interviewer "I don't care what kind of government they have over there, I never had such a good time in my life".[20] In June 1968 he made a public appeal for gun control following the assassination of his friend, Democratic Senator Robert F. Kennedy.[22] After his retirement from acting, Grant was active in a number of Republican causes. He introduced First Lady Betty Ford to the audience at the Republican National Convention in 1976.[21] He was also a vocal supporter of his friend Ronald Reagan during the 1980s.

[edit] Tribute

In 2001 a statue of Grant was erected in Millennium Square, a regenerated area next to the harbour in his city of birth, Bristol, England.

In November 2004, Grant was named "The Greatest Movie Star of All Time" by Premiere Magazine.[23] Richard Schickel, the film critic, said about Grant: "He's the best star actor there ever was in the movies."[24]

Ian Fleming stated that he partially had Cary Grant in mind when he created his suave super-spy, James Bond. Sean Connery was selected for the first James Bond movie because of his likeness to Grant. Likewise, the later Bond, Roger Moore, was also selected for sharing Grant's wry sense of humor.

John Cleese's character in the film A Fish Called Wanda was named Archie Leach,[25] a reference to Grant's legal birth name. (Grant himself had referenced an off-screen character named "Archie Leach" in His Girl Friday). The 1960s TV series The Flintstones featured a stone-age entertainer named "Gary Granite".

Cary Grant never did utter the phrase "Judy, Judy, Judy...". It was used by Tony Curtis who said it doing a Grant impression for the character of the millionaire in the movie Some Like it Hot, but Curtis heard it first when he went to visit his good friend Larry Storch's stand-up routine in New York and heard Storch say "Judy, Judy, Judy..." when Judy Garland walked into the club.[26]

In his "Schticks of One and a Half Dozen of the Other" medley, Allan Sherman created this lyric, sung to the tune of "Marianne", comically expressing jealousy: "All day, all night, 'Cary Grant!' / That's all I hear from my wife, is 'Cary Grant!' / What can he do that I can't? / Big deal! Big star! Cary Grant!"

[edit] Filmography

[edit] References

[edit] Notes

- ^ Donaldson, Maureen and William Royce. An Affair to Remember: My Life With Cary Grant. New York: Charter Books, 1990. ISBN 1-55773-371-6.

- ^ McMann, Graham. Cary Grant: A Class Apart. New York: Columbia UP, 1996, p. 271, n.13. Note: Although Grant's baptismal record records his middle name as "Alec", it is "Alexander" on his birth certificate.

- ^ Elsie Kingdom Retrieved: July 12, 2008.

- ^ Pace, Eric. "Movies' Epitome of Elegance Dies of a Stroke." New York Times, December 1, 1986. Retrieved: July 12, 2008.

- ^ The Statue of Liberty - Ellis Island Foundation, Inc.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, Cary Grant biography

- ^ Interview of Howard Hawks with Joseph McBride, in Hawks, Howard and Gerald Mast, Bringing Up Baby, p. 260. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1988.

- ^ Nelson and Grant 1992. p. 325.

- ^ McGilligan 2003, pp. 663–664.

- ^ TIME: Old Cary Grant Fine, 27 July 1962

- ^ a b c d Jaynes, Barbara Grant and Robert Trachtenberg. "Cary Grant: A Class Apart." tcm.com, Burbank, California: Turner Classic Movies (TCM) and Turner Entertainment, 2004.

- ^ White, Betty. "Cary Grant Today." Saturday Evening Post , March 1978. Retrieved: June 13, 2009.

- ^ McKelvey, Bob. "Cary Grant - Hollywood's Zany Lover Reaches 80." Detroit Free Press January 18, 1984. Retrieved: June 13, 2009.

- ^ Godfrey, Lionel. Cary Grant: The Light Touch. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1981. ISBN 0-31212-309-4.

- ^ "Sayers’ advice on education priceless for today’s athletes" The Lawrence Journal-World October 5, 2003 Accessed 9 August 2009

- ^ a b c d Higham and Moseley 1989

- ^ Blackwell, Vernon Patterson. From Rags to Bitches: An Autobiography. Los Angeles: General Publishing Group Inc., 1995. ISBN 1-88164-957.1.

- ^ Mann 2001, p. 154.

- ^ Laurents 2001, p. 131.

- ^ a b c Eliot, Marc. Cary Grant: The Biography. New York: Harmony Books, 2004. ISBN 1-40005-026-X.

- ^ a b Jaynes, Barbara Grant and Robert Trachtenberg. PBS: "Cary Grant: A Class Apart." Washington Post, May 26, 2005. Retrieved: June 13, 2009.

- ^ Nelson, Nancy. Evenings With Cary Grant: Recollections in His Own Words and by Those Who Knew Him Best. New York: Citadel, 2007. ISBN 978-0806524122.

- ^ "The 50 Greatest Movie Stars of All Time." Premiere Magazine. Retrieved: June 13, 2009.

- ^ Hammond, Pete. "Remembering Cary Grant at 100." Associated Press , (c/o CBS News), May 21, 2004. Retrieved: June 13, 2009.

- ^ Archie Leach (Character) - A Fish Called Wanda - IMDb - 1998

- ^ Cary Grant

[edit] Bibliography of cited references

- Bogdanovich, Peter. Who the Hell's in It: Portraits and Conversations. New York: A.A. Knopf, 2004. ISBN 0-37540-010-9.

- Eliot, Marc. Cary Grant: The Biography. New York: Aurum Press, 2005. ISBN 1-84513-073-1.

- Higham, Charles and Roy Moseley. Cary Grant: The Lonely Heart. London: Thompson Learning, 1997. ISBN 0-15115-787-1.

- Johannson, Warren and William A. Percy. Outing: Shattering the Conspiracy of Silence.. Kirkwood, NY: Harrington Park Press, 1994, pp. 146–147.

- Kael, Pauline. "The Man from Dream City - Cary Grant" - The New Yorker - July 14, 1975 - (reprinted in: Pauline Kael: For Keeps - 30 Years at the Movies. New York: Dutton, 1994.)

- Laurents, Arthur. Original Story by: A Memoir of Broadway and Hollywood. Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard Corp, 2001. ISBN 1-55783-467-9.

- Mann, William J. Behind the Screen: How Gays and Lesbians Shaped Hollywood, 1910-1969. New York: Viking, 2001. ISBN 0-67003-017-1.

- McCann, Graham. Cary Grant: A Class Apart. London: Fourth Estate, 1997. ISBN 1-85702-574-1.

- McGilligan, Patrick. Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light. New York: Regan Books, 2003. ISBN 0-06039-322-X.

- Morecambe, Gary; Sterling, Martin. Cary Grant: In Name Alone. London: Robson Books, 2001. ISBN 1-86105-466-1.

- Nelson, Nancy and Cary Grant. Evenings With Cary Grant: Recollections In His Own Words and By Those Who Loved Him Best. Thorndike, Maine: Thorndike Press, 1992. ISBN 1-56054-342-6.

- Russo, Vito. The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies [revised edition]. New York: Harrow & Row, 1987. ISBN 0-06096-132-5.

- Wansell, Geoffrey. Cary Grant: Dark Angel. London: Arcade, 1997. ISBN 1-55970-369-5.

[edit] External links

|

|

Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Cary Grant |

|

|

Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Cary Grant |

- Cary Grant at the Internet Movie Database

- Cary Grant at Allmovie

- Cary Grant at the TCM Movie Database

- Cary Grant at the Internet Broadway Database

- CaryGrant.net with filmography and historic reviews and photo galleries

- Cary Grant at Find a Grave

- "The Man From Dream City" by Pauline Kael, originally published in The New Yorker, July 14, 1975

- "Cary Grant: Style as a Martial Art" by Wu Ming, on the inclusion of Grant in their novel 54.

- Radio Shows: The Ultimate Cary Grant Pages. A vast collection of mp3 files.

Meher Baba's Life & Travels

Meher Baba's Life & Travels