Actress

1934

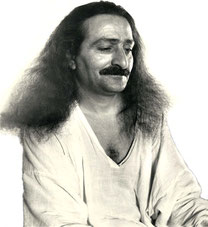

Baba also visited Paramount, Universal, Fox and Warner Brothers studios where he met many celebrities including the French singer Maurice Chevalier and movie producer Joseph Von Sternberg. He had a conversation with actor Will Rogers and was photographed with actress Alice Faye. In Hollywood, Baba also saw several films, one of which was Imitation of Life at the Pantages Theater on Hollywood Boulevard near Vine Street. Baba and his group took walks in the evenings. Minta once recollected, "There were the most fabulous sunsets. But they were not to be enjoyed. Baba walked terribly fast and we used to run to keep up with him."

Lord Meher Volume 6, Page 1937

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Alice Faye | |

|---|---|

from The Gang's All Here (1943) |

|

| Born |

Alice Jeane Leppert May 5, 1915 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died |

May 9, 1998 (aged 83) Rancho Mirage, California, U.S. |

| Spouse(s) | Phil Harris (1941–1995) |

Alice Faye (born Alice Jeane Leppert on May 5, 1915 – May 9, 1998) was an American actress and singer, called by the New York Times "one of the few movie stars to walk away from stardom at the peak of her career."[1] She is remembered first for her stardom at 20th Century Fox and, later, as the radio comedy partner of her husband, bandleader-comedian Phil Harris. She is also often associated with the Academy Award–winning standard, "You'll Never Know", which she introduced in the 1943 musical, Hello, Frisco, Hello.

Contents |

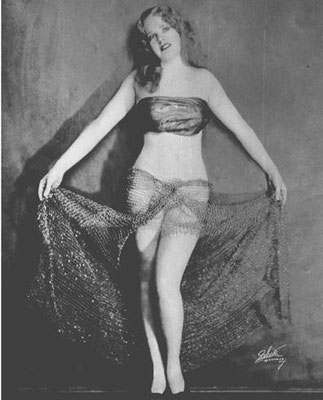

Early life

Born in New York City, she was the daughter of a New York police officer of German descent and his Irish-American wife, Charley and Alice Leppert. Faye's entertainment career began in vaudeville as a chorus girl (she failed an audition for the Ziegfeld Follies when it was revealed she was too young), before she moved to Broadway and a featured role in the 1931 edition of George White's Scandals. By this time, she had adopted her stage name and first reached a radio audience on Rudy Vallée's The Fleischmann Hour (1932–1934), where she may have met her future husband and comedy partner Phil Harris for the first time.

Film career

Meanwhile, she gained her first major film break in 1934, when Lilian Harvey abandoned the lead role in a film version of George White's 1935 Scandals, in which Vallee was also to appear. Hired first to perform a musical number with Vallee, Faye ended up as the female lead. And she became a hit with film audiences of the 1930s, particularly when Fox production head Darryl F. Zanuck made her his protege. He softened Faye from a wisecracking show girl to a youthful, yet somewhat motherly figure such as she played in a few Shirley Temple films.[2]

Faye also received a physical makeover, from being something of a singing version of Jean Harlow to sporting a softer look with a more natural tone to her blonde hair and more mature makeup. This transition was practically a plot point of 1938's Alexander's Ragtime Band, in which Faye's ascent (she plays a singer who moves from barrooms to fame) is dramatized by her increasingly elegant grooming.

Cast in musicals most of all, Faye introduced many popular songs to the hit parade. Considered less than serious as an actress and more than serious as a singer, Faye nailed what many critics consider her best acting performance in 1937's In Old Chicago. She more than held her own - in spite of a mild speech impediment - with co-stars such as Vallee, Al Jolson, Charlotte Greenwood, and Edward Everett Horton, as well as leading men such as Don Ameche, Tyrone Power, and John Payne.

Faye benefitted from color cinematography, and she shone in the splashy musical features that were a Fox trademark in the 1940s. She frequently played a performer, often one moving up in society, allowing for situations that ranged from the poignant to the comic. Films such as Weekend in Havana (1941) and That Night in Rio (1941), as a Brazilian aristocrat, made good use of Faye's husky singing voice, solid comic timing, and flair for carrying off the era's starry-eyed romantic storylines. 1943's The Gang's All Here is possibly the epitome of these films, with lavish production values and a range of supporting players (including the memorable Carmen Miranda in the indescribable "Lady in the Tutti-Frutti Hat" number) that camouflage the film's trivial plot and leisurely pacing.

In 1943, after taking a year off to have her first daughter, Faye starred in the Technicolor musical Hello, Frisco, Hello. It was in this film that she sang her trademark song, "You'll Never Know". Released at the height of World War II, the film became one of Faye's personal favorites and one of her highest-grossing pictures for Fox.

Faye's career continued until 1944 when she was cast in Fallen Angel, whose title became only too telling, as circumstances turned out. Designed ostensibly as Faye's vehicle, the film all but became her celluloid epitaph when Zanuck, trying to build his new protege Linda Darnell, ordered many Faye scenes cut and Darnell emphasized. When Faye saw a screening of the final product, she drove away from the Fox studio refusing to return, feeling she had been undercut deliberately by Zanuck.

According to her obituary in the New York Times, "Ms. Faye handed the keys to her dressing room to the studio gate guard and drove off the lot." In 1987 she told an interviewer, "When I stopped making pictures, it didn't bother me because there were so many things I hadn't done. I had never learned to run a house. I didn't know how to cook. I didn't know how to shop. So all these things filled all those gaps."[3]

Zanuck hit back, it is said, by having Faye blackballed for breach of contract, effectively ending her film career. Released in 1945, Fallen Angel was Faye's last film as a major Hollywood star.

But seventeen years after the Fallen Angel debacle, Faye went before the cameras again, in 1962's State Fair. While Faye received good reviews, the film was not a great success, and she made only infrequent cameo appearances in films thereafter.

Marriage and radio career

Faye's first marriage, to Tony Martin in 1937, ended in divorce in 1940. A year later, however, she married Phil Harris. This marriage became a plotline on an episode of the hit radio show hosted by Harris's then-employer, Jack Benny, which struck platinum in both Faye's personal and her professional life.

The couple had two daughters, Alice (b. 1942) and Phyllis (b. 1944), and began working in radio together as Faye's film career declined. First, they teamed to host a variety show on NBC, The Fitch Bandwagon, in 1946. Originally conceived as a music showcase, the Harrises' gently tart comedy sketches made them the show's breakout stars. By 1948, Fitch bowed away as sponsor in favour of Rexall, the pharmaceutical giant, and the show, now a strictly situation comedy with a music interlude each from husband and wife, was renamed The Phil Harris-Alice Faye Show.

Harris's comic talent was already familiar through his tenure on The Jack Benny Show, where he played Benny's wisecracking, jive-talking hipster bandleader. With their own show revamped to a sitcom, bandleader Harris and singer-actress Faye played themselves, raising two precocious children in and out of slightly zany situations, mostly involving Harris's band guitarist Frank Remley (Elliott Lewis), obnoxious delivery boy Julius Abruzzio (Walter Tetley, familiar as nephew Leroy on The Great Gildersleeve), Robert North as Faye's fictitious deadbeat brother, Willie, and sponsor's representative Mr. Scott (Gale Gordon), and usually involving bumbling, malapropping Harris needing rescue from acidly loving Faye.

The Harrises' two daughters were played on radio by Jeanine Roos and Anne Whitfield; written mostly by Ray Singer and Dick Chevillat, the show stayed on NBC radio fixture until 1954.

Faye singing ballads and swing numbers in her honey contralto voice was a regular highlight of the show, as was a knack for tart one-liners equal to her husband's. The show's running gags also included references to Alice's wealth from her film career ("I'm only trying to protect the wife of the money I love" was a typical Harris drollery) and occasional barbs by Faye aimed at her rift with Zanuck, usually referencing Fallen Angel in one or another way.

Later life and legacy

Faye and Harris continued various projects, individually and together, for the rest of their lives. Faye made a return to Broadway after forty-three years in a revival of Good News, with her old Fox partner John Payne (who was replaced by Gene Nelson). In later years, Faye became a spokeswoman for Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, promoting the virtues of an active senior lifestyle. The Faye-Harris marriage endured until Harris's death in 1995; before that, the couple donated a large volume of their entertainment memorabilia to Harris's hometown Linton, Indiana.

Three years after her husband's death, Alice Faye died in Rancho Mirage, California from stomach cancer at the age of 83. Her ashes rest beside those of Phil Harris at the mausoleum of the Forest Lawn Cemetery (Cathedral City) near Palm Springs, California. She has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in recognition of her contribution to Motion Pictures at 6922 Hollywood Boulevard. The Phil Harris-Alice Faye Show remains a favourite of old-time radio collectors.

The late rapper Tupac Shakur's mother, Afeni Shakur, whose birth name was Alice Faye Williams, was named after Faye.

Her voice, the New York Times wrote in her obituary, was "inviting." Irving Berlin was once quoted as saying that he would choose Ms. Faye over any other singer to introduce his songs. And George Gershwin and Cole Porter called her the "best female singer in Hollywood in 1937."[4]

Filmography

Features:

- George White's Scandals (1934)

- Now I'll Tell

- She Learned About Sailors

- 365 Nights in Hollywood

- George White's 1935 Scandals (1935)

- Every Night at Eight (1935)

- Music Is Magic (1935)

- King of Burlesque (1936)

- Poor Little Rich Girl (1936)

- Sing, Baby, Sing (1936)

- Stowaway (1936)

- In Old Chicago (1937)

- On the Avenue (1937)

- You Can't Have Everything (1937)

- Wake Up and Live (1937)

- You're a Sweetheart (1937)

- Sally, Irene and Mary (1938)

- Alexander's Ragtime Band (1938)

- Tail Spin (1939)

- Rose of Washington Square (1939)

- Hollywood Cavalcade (1939)

- Barricade (1939)

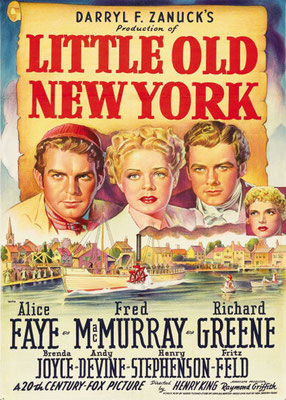

- Little Old New York (1940)

- Lillian Russell (1940)

- Tin Pan Alley (1940)

- That Night in Rio (1941)

- The Great American Broadcast (1941)

- Week-End in Havana (1941)

- Hello, Frisco, Hello (1943)

- The Gang's All Here (1943)

- Four Jills in a Jeep (1944)

- Fallen Angel (1945)

- State Fair (1962)

- Won Ton Ton, the Dog Who Saved Hollywood (1976)

- Every Girl Should Have One (1978)

- The Magic of Lassie (1978)

- A Century of Cinema (1994) (documentary)

- Carmen Miranda: Bananas Is My Business (1995) (documentary)

Short subjects:

- The Hollywood Gad-About (1934)

- Cinema Circus (1937)

- Screen Snapshots: Seeing Hollywood (1940)

- Screen Snapshots: Hawaii in Hollywood (1948)

- We Still Are (1985)

References

External links

|

|

Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Alice Faye |

- Alice Faye at the Internet Movie Database

- Alice Faye at the Internet Broadway Database

- Alice Faye at Find a Grave

- Photographs of Alice Faye

Meher Baba's Life & Travels

Meher Baba's Life & Travels