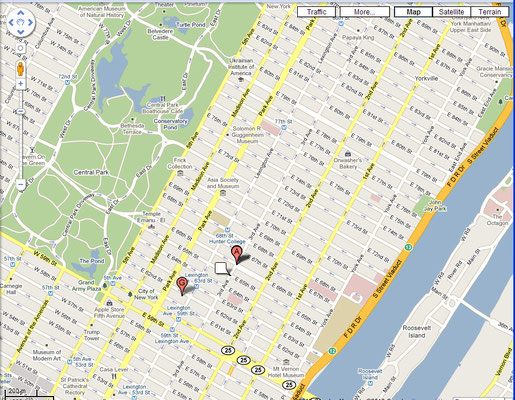

200 East 66th Street

Meher Baba visited Fred & Ella ( Fredella ) Winterfeldt's apartment in 1952

Baba watched an entire Yankees game on television in Fred and Ella's New York apartment; Fred was also at the Three Incredible Weeks in India in 1954.

Fredella: A Bouquet Of Memories

by Filis Frederick with Jeff Wolverton

7:30 A.M.: It was an incredible stormy day. A real blizzard had hit New York City. I had to go down five flights of stairs and stand on an icy, snow - piled street to try to get a taxi - very difficult with an injured hip. But there was dear Ella, ready with an umbrella, to run out and catch a cab for me. She did this every day of the blizzard, coming from her apartment a few blocks away.

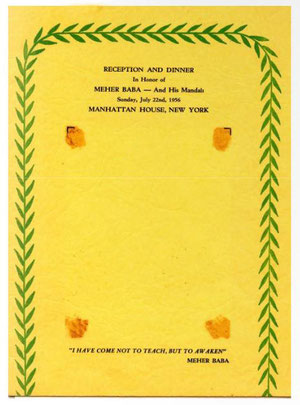

Such selfless service was so characteristic of Ella and her dear life companion Fred (they had become "Fredella" In the Baba-fashion of double names, like Elikit and Filadele). This selflessness wasn't for one or two close friends. The Winterfeldt home, first at Manhattan House on East 66th Street, New York and later on West 57th Street, was opened generously to the whole Baba family, to those In New York and those passing through, to those of the 50's on to those of the 60's. In the 70's this devoted couple served at Pine Lodge, at the Gateway of Meher Spiritual Center, with the same dedication. The meetings of the original Monday Night group were held at Manhattan House for many years; Baba Himself, with His women Mandali, visited their apartment in July, 1952.

I think It was this visit that gave rise to the story that Baba called Ella an angel. Actually, someone that afternoon said, "Baba, Ella is an angel." Baba smiled and gestured, "I am happy that My angel has come down with Me this time." He gave us a little discourse on angels, saying they do exist but have to become human beings in order to have the love for God necessary for Realization. There were archangels too, who might need only one or two births to "make it."

In 1952, In Scarsdale, N.Y., Baba had told the Winterfeldts He would like to bring the Eastern women to visit their apartment - to see TV, so new then. Ella asked, "For dinner, Baba?" Baba shook His head. "For lunch?" Again, Baba shook His head. Then He made a large "T" with His hands, for tea. It was a delightful afternoon. Coming later than expected, they missed a TV concert but saw Mickey Mantle hit a home run, which Mani stood up and imitated delightfully. Fred stood guard in the hall, to see that no men intruded or saw the women. Baba gestured to Ella, "Here is peace. I have greatly relaxed. I am coming back in 700 years." Ella used to add, when relating this, "And if He doesn't come back, well, we'll just have to pull Him down, won't we?" This was said with a childlike nod of her head, which conveyed the words, "And that's final."

Ella always treasured the couch on which Baba had lain and the chair Mehera sat in. Fredella brought the sofa and chair with them when they moved to Myrtle Beach, putting them in their living room. Many years Inter in 1980 at Pine Lodge. when Ella fell and injured her hip, she asked Jeff Wolverton to carry her to her "Baba sofa" to await the ambulance, the very sofa on which Baba had rested after His own hip Injury In 1952. In the latter years, when her health was failing. Ella would say to Jeff, after having breakfast together, "Take me to my friend," and there would pass the day, thinking of her beloved Meher Baba. It was her headquarters, or "heartquarters," during her last years.

I first met the Winterfeldts in the late 40's when Fredella lived on the West side. Fred was superintendent of a building there. One day in 1947-48, Murshida Ivy Duce, head of Sufism Reoriented, came looking for an apartment. Fred noticed a Baba button pinned inside her coat and asked her who that was; she said she would tell him later when she moved in.

Hearing of Baba was a turning point in their lives. Both Fred and Ella at this time were very depressed. Life seemed meaningless: they had contemplated suicide, and even bought a gun. But contact with the Master came at this crucial time. They both became Sufis and devoted Baba lovers; Ella did secretarial work for Ivy and served her diligently. Meanwhile they visited our Monday night group, formed after Elizabeth and Norina had left for India (1947). They liked our "free form" gathering very much.

http://www.manhattanhouse.com

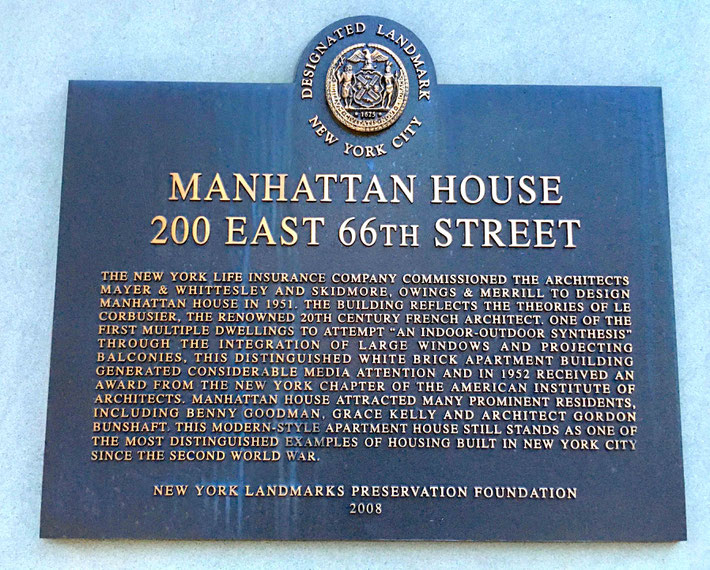

One of the most influential post-war buildings in New York City, Manhattan House

marked the beginning of the age of "white-brick monstrosities" in the eyes of some observers and the first big splash of International Style modernity in the city to others.

The mammoth development, which occupies the full block between Third and Second Avenues and 65th and 66th Streets, actually is clad in a light gray-brick, but niceties aside it presented a

"clean," "neat," almost Spartan appearance in distinct contrast to the historical styles of earlier periods and the Art Deco stylizations of the 1920s and 1930s.

Designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and Mayers & Whittlesley, it was built in 1950 and was, according to Robert A. M. Stern, Thomas Mellins and David Fishman in their superb book, "New

York 1960 Architecture and Urbanism Between The Second World War And The Bicentennial" (The Monacelli Press, 1995), "the most literal manisfestation in New York of Le Corbusier's postwar

conception of vertical living, which the master himself was not to realize until 1952 in his Unité d'Habitation at Marseilles."

"Together with elegantly thin window frames of white-painted metal and carefully

detailed balconies," the authors continued, "the glazed brick rendered Manhattan House a genteel manifesto for architecture's brave new world, a reassuring statement that Modernist minimalism had

more than cost benefits. In addition, the slab offered a distinct contrast with its mundane surroundings - the still-functioning Third Avenue El and its immediate neighbors, mostly old- and

new-law tenements. To protect the building's flanks, New York Life [Insurance Company, the developer] acquired the row of tenements on the north side of Sixty-sixth Street, renovated their

interiors and painted the facades a tasteful dark gray trimmed in white. The principal innovations of Manhattan House were the bold scale resulting from its single-slab configuration; the

departure from traditional urban space making in the refusal to hold the street front except at the base; and the blurring of distinctions between exterior and interior space, as well as front

and back yards, by the use of large amounts of glazing at the lobby level. In discussing this last point, the editors of Architectural Record, presumably quoting form a New York Life press

release, said that 'the entire development carries out on a large scale, in a big city, an indoor-outdoor synthesis hitherto found mostly in modern country homes.'"

The insurance company also protected its investment and views by erecting a low-rise commercial structure that included the Beekman movie theater at 1254 Second Avenue across from Manhattan House

that was closed in the early years of this millennium.

The insurance company originally had acquired not only the block on which Manhattan House is sited, but also the block just to the south for which it planned a large parking garage topped by a

public park. Three hundred of the garage's 1,400 parking spaces were to be reserved for the residents of Manhattan House. The plans for this block, however, would be shelved.

Gordon Bunshaft, the principal architect with Skidmore, Owings & Merrill for the project, took an apartment for himself at Manhattan House and at one time Grace Kelly, the actress, also

rented an apartment.

The building, which has a roof deck, has five projecting bays, each with two balconies and its entrances are along a curved driveway on 66th Street, which was widened on this block because of the

project. There are several entrances along the driveway, which is lushly landscaped and the lobbies have floor-to-ceiling windows that permit views from the driveway through to the development's

large gardens on the south side, that are walled from 65th Street. A one-story commercial base along Third Avenue originally housed a large Longchamps restaurant that had its own outdoor terrace

facing the gardens.

Manhattan House is a 19-story building with 581 apartments, many with balconies and some with fireplaces.

In 2005, New York Life Insurance Company sold the property to Manchester Real Estate, of which N. Richard Kalikow and Jeremiah W. O'Connor Jr., were principals, for about $625 million.

Plans to convert the building to a residential condominium ran into difficulties, however, when the partners got involved in litigation and a tenants' group filed suit to block the

conversion.

According to the second amendment to the condominium offering plan for Manhattan House, the famous apartment complex on the full block bounded by Third and Second Avenues and 65th and 66th

Streets, which was dated October 11, 2007, N. Richard Kalikow was longer a principal of the plan's sponsor and Jeremiah W. O'Connor Jr. is the sole principal.

The amendment said that the sponsor has entered into mortgage loans with HSH Nordbank AG, New York Branch and that the sponsor must declare the plan effective no later than June 1, 2008. The

amendment also said that bona fide tenants in occupancy have the exclusive right for 30 days from the filing of the amendment to purchase their units at a 15 percent discount from non-tenant

purchase prices.

The amendment indicated that the current total purchase price for tenants for about $958 million.

A vacant three-bedroom apartment with three baths and a total of 1,675 square feet on the 20th floor in the E wing has a tenant price of $2,720,000 and a non-tenant price of $3,100,000. A vacant

one-bedroom apartment with one bath and 953 square feet on the 15th floor in the same wing has a tenant price of $1,077,987 and a non-tenant price of $1,268,220. A vacant studio apartment with

one bath and 586 square feet in the same wing has a tenant price of $604,928 and a non-tenant price of $711,780.

Air-conditioning was not included when it was completed, although the building subsequently allowed protruding air-conditioners and the condo conversion plan included an upgrading of the building

that including central air-conditioning.

Although scores of apartment houses on the Upper East Side would try to mimic the success of Manhattan House with light-colored brick facades and balconies, there were not too many full-block

opportunities.

One that is somewhat similar, however, is Imperial House, which was designed by Emery Roth & Sons in 1960 and is nearby at 69th Street and Third Avenue and also features extensive gardens and

a very large, windowed lobby but has a center tower.

Building has driveway entrances

Building has driveway entrances

In their excellent book, "The A.I.A. Guide to New York City, Third Edition"

(Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1988), Norval White and Elliot Willensky remarked that the building's "balconies become the principal ornament, but unfortunately they are small and precarious for

those with any trace of vertigo." "(Sometime in the 1980s the original windows were replaced - with regrettable aesthetic results.) The block was occupied from 1896 to 1949 by the Third Avenue

Railway System car barns where horsecars and then electric streetcars were housed. It was an elaborate French Second Empire mansarded 'palace.'"

This section of Third Avenue has been subsequently developed with many luxury apartment towers and there is convenient local shopping and good public transportation.

An October 31, 2008 article by David Jones indicated that "the record $1.1 billion Manhattan House conversion on the Upper East Side has run into resistance from several major commercial banks that have either refused to finance condo deals there or demanded exorbitant down payments from contracted buyers."

The text of Mr. Jones's article was as follows:

Sources familiar with the building said at least a dozen condo buyers have either been turned down for loans, or asked to provide 30 to 50 percent cash deposits, which in some cases forced them to postpone the scheduled closing of their units.

As a result, some buyers fear they will have to purchase their apartments entirely in cash or risk walking away from the building because the condo agreements did not include a mortgage contingency clause.

"They got caught in the perfect storm on the precipice of this [credit market] disaster," said a source.

Manhattan House is one of the city's largest and most high-profile condo conversions. But, it is not the only condo building in New York facing problems. Buyers have begun to bail out of condos like 25 Broad and 20 Pine Street in the Financial District, while lenders have shied away from some Battery Park City buildings because they sit on long-term ground leases.

According to sources and records filed with the city Department of Finance, at least eight of the more than 120 apartments sold at Manhattan House have closed since the condo plan was approved by state regulators. Of those eight, four sales were cash transactions, three were loans approved by Wells Fargo and one was a loan approved JPMorgan Chase.

Neil Bader, area manager at Wells Fargo Home Mortgage, confirmed that the bank has pre-approved the building and is actively working with buyers to finance apartment deals.

"There is nothing inherent about Manhattan House or the financial efficacy of that building that would have any impact on getting lower loan to value," said Bader.

However, a Citibank spokesman confirmed that the bank will not write loans to finance Manhattan House buyers, saying the building did not meet Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac guidelines, which are used to assess risk levels in newly constructed or converted condos. "We might look at that building in the future," the spokesman said.

JPMorgan Chase spokesman Mike Fusco, while declining to comment on Manhattan House specifically, said Fannie and Freddie "are asking us to make loans only if 51 percent of the units are sold at presale. He added, however, that the bank is actively pursuing new loans to fill the void left by other conservative or collapsed banks, and during the second-quarter had the biggest year-over-year market share gain among the nation's top lenders.

The decisions come at a critical time for Manhattan House owner O'Connor Capital Partners, which recently sold the building's retail space for $86 million and used part of the proceeds to pay down its loan balance from German-lender HSH Nordbank.

In October 2007, the New York-based developer borrowed $750 million from HSH Nordbank to finance the conversion of Manhattan House, which was acquired for a record $623 million in 2005.

HSH Nordbank initially syndicated the loan among a group of banks, giving each a piece of the loan and reducing the risk for all of the lenders. The banks involved in the deal included Emigrant Savings, Bank of America, Bank of New York, HSBC, ING, M&T and Wells Fargo.

However, a September 2008 report in Commercial Mortgage Alert confirmed that the partner banks forced HSH to take the loan back, amid concerns about the conversion. The report said HSH would cut most of its New York staff and curtail lending in the U.S., where it had about $6 billion in mortgages that it was unable to syndicate.

HSH Nordbank and Manhattan House officials declined comment.

Legal and financial experts said the tight lending environment not only reflects increased concern about financing highly-leveraged projects, but also highlights the inability to securitize super jumbo loans in the multi-million dollar range. Loans of this size are often considered "portfolio loans" that would be carried on the banks' own books and not sold off in the secondary market.

"Most lenders have completely changed their loan-to-value guidelines," said Debra Schultz, director and senior mortgage consultant at Manhattan Mortgage Co., the largest residential mortgage broker in New York. "If you want to borrow 90 percent on a $3 million to $4 million property, they want no part of it."

Schultz said that many of her wealthy clients cannot get financing from commercial banks, forcing her to use private lenders, which include hedge funds and the private banking departments of many investment banks.

Manhattan House, with a total of 583 total units, has a large number of apartments that have not been sold, or even been renovated yet, which means the developer will need to spend additional funds on construction and find a way to generate revenue in a weak real estate market.

Katherine Fleming, a Manhattan House tenant since 1991, just closed a deal to buy her apartment for $1.45 million in cash and remains confident in the building's performance. "The building has a future or I wouldn't have put my money down," she said.

Manhattan House has about 190 rent-stabilized tenants and 35 market-rate tenants. City records show that the eight recorded sales range from about $837,343 to $2.72 million.

Adam Leitman Bailey, attorney for the Manhattan House Tenants Association and an advisor to some of the buyers, declined comment.

Critics of the building note that O'Connor and former partner Richard Kalikow bought Manhattan House at the height of the real estate boom for a record $623 million, which averages more than $1 million per apartment. So even if O'Connor were to consider renting out units, he would never be able to generate enough income to pay his "monthly nut," sources said.

"He paid way too much to justify it as a rental," said David Berger, managing principal at Rosewood Realty Group. "In a good market the numbers wouldn't underwrite as a rental."

As noted earlier, O'Connor is not the only new condo facing difficulties beginning in the fiscal crisis that began in 2008.

And, developer Kent Swig is facing lawsuits from unpaid contractors at 25 Broad Street and at the Sheffield at 322 West 57th Street, He recently shut down his entire 25 Broad sales office and some buyers have said they will walk from their deposits.

"The very aggressive people who banked on these projects selling out at a very large sellout number are going to be faced with challenges," said one leading condo broker, who asked not to be identified. "When anybody in Manhattan House wants to sell their [unit] they're going to be competing with the sponsor."

Herrick Feinstein attorney Doug Heller said one of his clients, a developer with multiple condo projects, has been unable to get financing for many of his buyers. Heller worries that new government regulations will further limit the ability of condo buyers to qualify for financing.

"What I'm hearing from my clients is that this might even be the tip of the iceberg," he said.

Millionaires’ Row

At Manhattan House, tenants and developers are battling over a condo conversion that may not make much sense anyway.

|

|

(Photo: Scott Bintner/Courtesy of Property Shark)

|

Condo conversions are notoriously difficult, but the drama unfurling at Manhattan House, a 583-unit East 66th Street building that’s the epitome of the giant postwar white-brick, is reaching legendary proportions. Lawyers and legislators are hollering, and “animosity would not begin to describe what’s going on,” says Gail Amsterdam, who has lived in the building for sixteen years.

Tenants claim owners N. Richard Kalikow and Jeremiah O’Connor, who bought it last year for $620 million in the second-most-expensive sale of a rental building ever (topped only by the Stuyvesant Town deal), are muscling elderly rent-stabilized and market-rate tenants out the door. Those who’ve stayed gripe about renovations. One man well over 80 says his rent checks have gone uncashed; Amsterdam even blames the recent death of her uncle, Martin Burwick, on the resultant stress. (Publicist Steve Solomon, speaking for Kalikow and O’Connor, says “there’s absolutely no truth” to the harassment claims.)

It’s the stuff headlines are made of, and indeed the mess has made the papers repeatedly. But is it worth it for the developers? Their prices, around $1,500 per square foot, are pretty high, and questions linger over whether the cooling condo market will support them. A 1,482-square-foot two-bedroom on the seventh floor, for instance, is priced at $2.2 million; a 2,367-square-foot on a higher floor, $3.8 million. (Current tenants will get a slight discount.) In comparison, a 1,475-square-foot unit at the Philip Johnson–designed Metropolitan is listed in the offering plan at $1.68 million; a 2,200-square-foot three-bedroom on East End Avenue is $3.25 million. Even for a place that once housed Grace Kelly, those are ambitious numbers. “You’re going to be living with a lot of renters … My clientele would not be interested in that,” scoffs one uptown broker.

Furthermore, even with a planned makeover—roof deck, library, billiard room, fitness center—Manhattan House’s owners can’t do much about its modest ceiling heights and ungainly exterior. Appraiser Jonathan Miller, while noting the building’s appealingly large units, says the conversion “may fly, but there’s more competition out there.” Says Amsterdam, “If I was going to spend $2 million on a two-bedroom, I’d go to Park Avenue … You can teach an old dog new tricks, but an old dog’s an old dog.”

Solomon maintains “a lot of thought went into the pricing,” adding that he expects many residents to buy in. Some of those tenants wonder if they’re wanted, though. “We told them many times we were interested, and they [sent] us an eviction notice,” says software executive Ben Weintraub, who’s lived there for eleven years. Ditto Douglas Altchek, a doctor and 25-year Manhattan House resident who suspects that the developers would prefer the higher prices outside sales would bring. “I’m ready, willing, and able,” he says, sighing. “Why on earth they haven’t negotiated with me, I don’t know.”

New York Times

Meher Baba's Life & Travels

Meher Baba's Life & Travels