London Underground

London Underground

| London Underground | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Info | |

| Locale | Greater London, Chiltern, Epping Forest, Three Rivers and Watford |

| Transit type | Rapid transit |

| Number of lines | 11 |

| Number of stations | 270 served (260 owned) |

| Daily ridership |

2.95 million (approximate)[1][2] 3.4 million (weekdays) (approximate)[3] |

| Operation | |

| Began operation | 10 January 1863 |

| Operator(s) | Transport for London |

| Technical | |

| System length | 400 kilometres (250 mi) (approximate)[1] |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) Standard gauge |

|

Part of a series of articles on The Tube |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

Overview

History |

|

The London Underground is a rapid transit system serving a large part of Greater London and neighbouring areas of Essex, Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire in the UK. Despite the name, it is not the only underground railway to have been built in London – there was also the now defunct London Post Office Railway, Kingsway Tramway Subway and Tower Subway. There are localised railways in use today – the Docklands Light Railway and the Tramlink. There is also the London Overground service. With its first section opening in 1863, it was the first underground railway system in the world.[4] In 1890 it became the first to operate electric trains.[5] Despite the name, about 55% of the network is above ground. It is usually referred to officially as 'the Underground' and colloquially as the Tube, although the latter term originally applied only to the deep-level bored lines, along which run slightly lower, narrower trains along standard-gauge track, to distinguish them from the sub-surface "cut and cover" lines that were built first. More recently this distinction has been lost and the whole system is now referred to as The Tube, even in recent years by its operator in official publicity.[6]

The earlier lines of the present London Underground network were built by various private companies. Apart from the main line railways, they became part of an integrated transport system in 1933 when the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB) or London Transport was created. The underground network became a single entity in 1985, when the UK government created London Underground Limited (LUL).[7] Since 2003 LUL has been a wholly owned subsidiary of Transport for London (TfL), the statutory corporation responsible for most aspects of the transport system in Greater London, which is run by a board and a commissioner appointed by the Mayor of London.[8]

The Underground has 270 stations and around 400 kilometres (250 mi) of track,[1] making it the second longest metro system in the world by route length after the Shanghai Metro.[9] It also has one of the highest number of stations. In 2007, more than one billion passenger journeys were recorded,[3] making it the third busiest metro system in Europe after Paris and Moscow.

The tube map, with its schematic non-geographical layout and colour-coded lines, is considered a design classic, and many other transport maps worldwide have been influenced by it.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] History

Railway construction in the United Kingdom began in the early 1800s. By 1854 six railway terminals had been built just outside the centre of London: London Bridge, Euston, Paddington, King's Cross, Bishopsgate and Waterloo. At this point, only Fenchurch Street Station was located in the actual City of London. Traffic congestion in the city and the surrounding areas had increased significantly in this period, partly due to the need for rail travellers to complete their journeys into the city centre by road. The idea of building an underground railway to link the City of London with the mainline terminals had first been proposed in the 1830s, but it was not until the 1850s that the idea was taken seriously as a solution to traffic congestion.[10]

[edit] The first underground railways

In 1854 an Act of Parliament was passed approving the construction of an underground railway between Paddington Station and Farringdon Street via King's Cross which was to be called the Metropolitan Railway. The Great Western Railway (GWR) gave financial backing to the project when it was agreed that a junction would be built linking the underground railway with their mainline terminus at Paddington. GWR also agreed to design special trains for the new subterranean railway.

A shortage of funds delayed construction for several years. The fact that this project got under way at all was largely due to the lobbying of Charles Pearson, who was Solicitor to the City of London Corporation at the time. Pearson had supported the idea of an underground railway in London for several years. He advocated plans for the demolition of the unhygienic slums which would be replaced by new accommodation for their inhabitants in the suburbs, with the new railway providing transportation to their places of work in the city centre. Although he was never directly involved in the running of the Metropolitan Railway, he is widely credited as being one of the first true visionaries behind the concept of underground railways. And in 1859 it was Pearson who persuaded the City of London Corporation to help fund the scheme. Work finally began in February 1860, under the guidance of chief engineer John Fowler. Pearson died before the work was completed.

The Metropolitan Railway opened on 10 January 1863.[7] Within a few months of opening it was carrying over 26,000 passengers a day.[11] The Hammersmith and City Railway was opened on 13 June 1864 between Hammersmith and Paddington. Services were initially operated by GWR between Hammersmith and Farringdon Street. By April 1865 the Metropolitan had taken over the service. On 23 December 1865 the Metropolitan's eastern extension to Moorgate Street opened. Later in the decade other branches were opened to Swiss Cottage, South Kensington and Addison Road, Kensington (now known as Kensington Olympia). The railway had initially been dual gauge, allowing for the use of GWR's signature broad gauge rolling stock and the more widely used standard gauge stock. Disagreements with GWR had forced the Metropolitan to switch to standard gauge in 1863 after GWR withdrew all its stock from the railway. These differences were later patched up, however broad gauge was totally withdrawn from the railway in March 1869.

On 24 December 1868, the Metropolitan District Railway began operating services between South Kensington and Westminster using Metropolitan Railway trains and carriages. The company, which soon became known as "the District", was first incorporated in 1864 to complete an Inner Circle railway around London in conjunction with the Metropolitan. This was part of a plan to build both an Inner Circle line and Outer Circle line around London.

A fierce rivalry soon developed between the District and the Metropolitan. This severely delayed the completion of the Inner Circle project as the two companies competed to build far more financially lucrative railways in the suburbs of London. The London and North Western Railway (LNWR) began running their Outer Circle service from Broad Street via Willesden Junction, Addison Road and Earl's Court to Mansion House in 1872. The Inner Circle was not completed until 1884, with the Metropolitan and the District jointly running services. In the meantime, the District had finished its route between West Brompton and Blackfriars in 1870, with an interchange with the Metropolitan at South Kensington. In 1877, it began running its own services from Hammersmith to Richmond, on a line originally opened by the London & South Western Railway (LSWR) in 1869. The District then opened a new line from Turnham Green to Ealing in 1879[12] and extended its West Brompton branch to Fulham in 1880. Over the same decade the Metropolitan was extended to Harrow-on-the-Hill station in the north-west.

The early tunnels were dug mainly using cut-and-cover construction methods. This caused widespread disruption and required the demolition of several properties on the surface. The first trains were steam-hauled, which required effective ventilation to the surface. Ventilation shafts at various points on the route allowed the engines to expel steam and bring fresh air into the tunnels. One such vent is at Leinster Gardens, W2.[13] In order to preserve the visual characteristics in what is still a well-to-do street, a five-foot-thick (1.5 m) concrete façade was constructed to resemble a genuine house frontage.

On 7 December 1869 the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LB&SCR) started operating a service between Wapping and New Cross Gate on the East London Railway (ELR) using the Thames Tunnel designed by Marc Brunel, who designed the revolutionary tunnelling shield method which made its construction not only possible, but safer, and completed by his son Isambard Kingdom Brunel. This had opened in 1843 as a pedestrian tunnel, but in 1865 it was purchased by the ELR (a consortium of six railway companies: the Great Eastern Railway (GER); London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LB&SCR); London, Chatham and Dover Railway (LCDR); South Eastern Railway (SER); Metropolitan Railway; and the Metropolitan District Railway) and converted into a railway tunnel. In 1884 the District and the Metropolitan began to operate services on the line.

By the end of the 1880s, underground railways reached Chesham on the Metropolitan, Hounslow, Wimbledon and Whitechapel on the District and New Cross on the East London Railway. By the end of the 19th century, the Metropolitan had extended its lines far outside of London to Aylesbury, Verney Junction and Brill, creating new suburbs along the route, later publicised by the company as Metro-land. Right up until the 1930s the company maintained ambitions to be considered as a main line rather than an urban railway, ambitions that are still continued somewhat today.

[edit] First tube lines

Following advances in the use of tunnelling shields, electric traction and deep-level tunnel designs, later railways were built even further underground. This caused much less disruption at ground level and it was therefore cheaper and preferable to the cut-and-cover construction method.

The City & South London Railway (C&SLR, now part of the Northern Line) opened in 1890, between Stockwell and the now closed original terminus at King William Street. It was the first "deep-level" electrically operated railway in the world.[14] By 1900 it had been extended at both ends, to Clapham Common in the south and Moorgate Street (via a diversion) in the north. The second such railway, the Waterloo and City Railway (W&CR), opened in 1898.[15] It was built and run by the London and South Western Railway.

On 30 July 1900, the Central London Railway (now known as the Central Line) was opened,[15] operating services from Bank to Shepherd's Bush. It was nicknamed the "Twopenny Tube" for its flat fare and cylindrical tunnels;[16] the "tube" nickname was eventually transferred to the Underground system as a whole. An interchange with the C&SLR and the W&CR was provided at Bank. Construction had also begun in August 1898 on the Baker Street & Waterloo Railway, however work came to a halt after 18 months when funds ran out.[17]

[edit] Integration

In the early 20th century the presence of six independent operators running different Underground lines caused passengers substantial inconvenience; in many places passengers had to walk some distance above ground to change between lines. The costs associated with running such a system were also heavy, and as a result many companies looked to financiers who could give them the money they needed to expand into the lucrative suburbs as well as electrify the earlier steam operated lines. The most prominent of these was Charles Yerkes, an American tycoon who secured the right to build the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway (CCE&HR) on 1 October 1900, today also part of the Northern Line. In March 1901, he effectively took control of the District and this enabled him to form the Metropolitan District Electric Traction Company (MDET) on 15 July. Through this he acquired the Great Northern and Strand Railway and the Brompton and Piccadilly Circus Railway in September 1901, the construction of which had already been authorised by Parliament, together with the moribund Baker Street & Waterloo Railway in March 1902. The GN&SR and the B&PCR evolved into the present-day Piccadilly Line. On 9 April the MDET evolved into the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL). The UERL also owned three tramway companies and went on to buy the London General Omnibus Company, creating an organisation colloquially known as "the Combine" which went on to dominate underground railway construction in London until the 1930s.

With the financial backing of Yerkes, the District opened its South Harrow branch in 1903 and completed its link to the Metropolitan's Uxbridge branch at Rayners Lane in 1904—although services to Uxbridge on the District did not begin until 1910 due to yet another disagreement with the Metropolitan. Today, District Line services to Uxbridge have been replaced by the Piccadilly Line. By the end of 1905, all District Railway and Inner Circle services were run by electric trains.

The Baker Street & Waterloo Railway opened in 1906, soon branding itself the Bakerloo, and by 1907 it had been extended to Edgware Road in the north and Elephant & Castle in the south. The newly named Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway, combining the two projects acquired by MDET in September 1901, also opened in 1906. With tunnels at an impressive depth of 200 feet below the surface, it ran from Finsbury Park to Hammersmith; a single station branch to Strand (later renamed Aldwych) was added in 1907. In the same year the CCE&HR opened from Charing Cross to Camden Town, with two northward branches, one to Golders Green and one to Highgate (now Archway).

Independent ventures did continue in the early part of the 20th century. The independent Great Northern & City Railway opened in 1904 between Finsbury Park and Moorgate. It was the only tube line of sufficient diameter to be capable of handling main line stock, and it was originally intended to be part of a main line railway. However money soon ran out and the route remained separate from the main line network until the 1970s. The C&SLR was also extended northwards to Euston by 1907.

In early 1908, in an effort to increase passenger numbers, the underground railway operators agreed to promote their services jointly as "the Underground", publishing new adverts and creating a free publicity map of the network for the purpose. The map featured a key labelling the Bakerloo Railway, the Central London Railway, the City & South London Railway, the District Railway, the Great Northern & City Railway, the Hampstead Railway (the shortened name of the CCE&HR), the Metropolitan Railway and the Piccadilly Railway. Other railways appeared on the map but with much less prominence; these included the Waterloo & City Railway and part of the ELR, which were both owned by main line railway companies at the time. As part of the process, "The Underground" name appeared on stations for the first time[18] and electric ticket-issuing machines were also introduced. This was followed in 1913 by the first appearance of the famous circle and horizontal bar symbol, known as "the roundel",[19] designed by Edward Johnston.[18] In January 1933 the UERL experimented with a new diagrammatic map of the Underground, designed by Harry Beck and first issued in pocket-size form. It was an immediate success with the public and is now commonly regarded as a design classic; an updated version is still in use today.[20]

Meanwhile, on 1 January 1913 the UERL absorbed two other independent tube lines, the C&SLR and the Central London Railway. As the Combine expanded, only the Metropolitan stayed away from this process of integration, retaining its ambition to be considered as a main line railway. Proposals were put forward for a merger between the two companies in 1913 but the plan was rejected by the Metropolitan. In the same year the company asserted its independence by buying out the cash strapped Great Northern and City Railway, a predecessor to the Piccadilly Line. It also sought a character of its own. The Metropolitan Surplus Lands Committee had been formed in 1887 to develop accommodation alongside the railway and in 1919 Metropolitan Railway Country Estates Ltd. was founded to capitalise on the post-World War One demand for housing. This ensured that the Metropolitan would retain an independent image until the creation of London Transport in 1933.

The Metropolitan also sought to electrify its lines. The District and the Metropolitan had agreed to use the low voltage DC system for the Inner Circle, comprising two electric rails to power the trains, back in 1901. At the start of 1905 electric trains began to work the Uxbridge branch and from 1 November 1906 electric locomotives took trains as far as Wembley Park where steam trains took over. This changeover point was moved to Harrow-on-the-Hill on 19 July 1908. The Hammersmith & City branch had also been upgraded to electric working on 5 November 1906. The electrification of the ELR followed on 31 March 1913, the same year as the opening of its extension to Whitechapel and Shoreditch. Following the Grouping Act of 1921, which merged all the cash strapped main line railways into four companies (thus obliterating the original consortium that had built the ELR), the Metropolitan agreed to run passenger services on the line.

The Bakerloo Line extension to Queen's Park was completed in 1915, and the service extended to Watford Junction via the London and North Western Railway tracks in 1917. The extension of the Central Line's branch to Ealing Broadway was delayed by the war until 1920.

The major development of the 1920s was the integration of the CCE&HR and the C&SLR and extensions to form what was to become the Northern line. This necessitated enlargement of the older parts of the C&SLR, which had been built on a modest scale. The integration required temporary closures during 1922—24. The Golders Green branch was extended to Edgware in 1924, and the southern end was extended to Morden in 1926.

The Watford branch of the Metropolitan opened in 1925 and in the same year electrification was extended to Rickmansworth. The last major work completed by the Metropolitan was the branch to Stanmore which opened in 1932 and which is now part of the Jubilee Line.

By 1933 the Combine had completed the Cockfosters branch of the Piccadilly Line, with through services running (via realigned tracks between Hammersmith and Acton Town) to Hounslow West and Uxbridge.

[edit] London Transport

In 1933 the Combine, the Metropolitan and all the municipal and independent bus and tram undertakings were merged into the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB), a self-supporting and unsubsidised public corporation which came into being on 1 July 1933. The LPTB soon became known as London Transport (LT).

Shortly after it was created, LT began the process of integrating the underground railways of London into one network. All the separate railways were renamed as "lines" within the system: the first LT version of Beck's map featured the District Line, the Bakerloo Line, the Piccadilly Line, the Edgware, Highgate and Morden Line, the Metropolitan Line, the Metropolitan Line (Great Northern & City Section), the East London Line, and the Central London Line. The shorter names Central Line and Northern Line were adopted for two lines in 1937. The Waterloo & City line was not originally included in this map as it was still owned by a main line railway and not part of LT, but was added in a less prominent style, also in 1937.

LT announced a scheme for the expansion and modernisation of the network entitled the New Works Programme, which had followed the announcement of improvement proposals for the Metropolitan Line. This consisted of plans to extend some lines, to take over the operation of others from main-line railway companies, and to electrify the entire network. During the 1930s and 1940s, several sections of main-line railways were converted into surface lines of the Underground system. The oldest part of today's Underground network is the Central line between Leyton and Loughton, which opened as a railway seven years before the Underground itself.

LT also sought to abandon routes which made a significant financial loss. Soon after the LPTB started operating, services to Verney Junction and Brill on the Metropolitan Railway were stopped. The renamed Metropolitan Line terminus was moved to Aylesbury.

The outbreak of World War II delayed all the expansion schemes. From mid-1940, the Blitz led to the use of many Underground stations as shelters during air raids and overnight. The Underground helped over 200,000 children escape to the countryside and sheltered another 177,500 people. The authorities initially tried to discourage and prevent people from sleeping in the tube, but later supplied 22,000 bunks, latrines, and catering facilities. After a time there were even special stations with libraries and classrooms for night classes. Later in the war, eight London deep-level shelters were constructed under stations, ostensibly to be used as shelters (each deep-level shelter could hold 8,000 people) though plans were in place to convert them for a new express line parallel to the Northern line after the war. Some stations (now mostly disused) were converted into government offices: for example, Down Street was used for the headquarters of the Railway Executive Committee and was also used for meetings of the War Cabinet before the Cabinet War Rooms were completed;[21] Brompton Road was used as a control room for anti-aircraft guns and the remains of the surface building are still used by London's University Royal Naval Unit (URNU) and University London Air Squadron (ULAS).

After the war one of the last acts of the LPTB was to give the go-ahead for the completion of the postponed Central Line extensions. The western extension to West Ruislip was completed in 1948, and the eastern extension to Epping in 1949; the single-line branch from Epping to Ongar was taken over and electrified in 1957.

[edit] Nationalisation

On 1 January 1948 London Transport was nationalised by the incumbent Labour government, together with the four remaining main line railway companies, and incorporated into the operations of the British Transport Commission (BTC). The LPTB was replaced by the London Transport Executive (LTE). This brought the Underground under the remit of central government for the first time in its history.

The implementation of nationalised railways was a move of necessity as well as ideology. The main-line railways had struggled to cope with a war economy in the First World War and by the end of World War Two the four remaining companies were on the verge of bankruptcy. Nationalisation was the easiest way to save the railways in the short term and provide money to fix wartime damage. The BTC necessarily prioritised the reconstruction of its main-line railways over the maintenance of the Underground network. The unfinished parts of the New Works Programme were gradually shelved or postponed.

However the BTC did authorise the completion of the electrification of the network, seeking to replace steam locomotives on the parts of the system where they still operated. This phase of the program was completed when the Metropolitan Line was electrified to Chesham in 1960. Steam locomotives were fully withdrawn from London Underground passenger services on 9 September 1961, when British Railways took over the operations of the Metropolitan Line between Amersham and Aylesbury. The last steam shunting and freight locomotive was withdrawn from service in 1971.[19]

In 1963 the LTE was replaced by the London Transport Board, directly accountable to the Ministry of Transport.

[edit] GLC Control

On 1 January 1970, the Greater London Council (GLC) took over responsibility for London Transport, again under the formal title London Transport Executive. This period is perhaps the most controversial in London's transport history, characterised by staff shortages and a severe lack of funding from central government. In 1980 the Labour-led GLC began the 'Fares Fair' project, which increased local taxation in order to lower ticket prices. The campaign was initially successful and usage of the Tube significantly increased. But serious objections to the policy came from the London Borough of Bromley, an area of London which has no Underground stations. The Council resented the subsidy as it would be of little benefit to its residents. The council took the GLC to the Law Lords who ruled that the policy was illegal based on their interpretation of the Transport (London) Act 1969. They ruled that the Act stipulated that London Transport must plan, as far as was possible, to break even. In line with this judgement, 'Fares Fair' was therefore reversed, leading to a 100% increase in fares in 1982 and a subsequent decline in passenger numbers. The scandal prompted Margaret Thatcher's Conservative Government to remove London Transport from the GLC's control in 1984, a development that turned out to be a prelude to the abolition of the GLC in 1986.

However the period saw the first real postwar investment in the network with the opening of the carefully planned Victoria Line, which was built on a diagonal northeast-southwest alignment beneath central London, incorporating centralised signalling control and automatically driven trains. It opened in stages between 1968 and 1971. The Piccadilly line was extended to Heathrow Airport in 1977, and the Jubilee Line was opened in 1979, taking over the Stanmore branch of the Bakerloo Line, with new tunnels between Baker Street and Charing Cross. There was also one important legacy from the 'Fares Fair' scheme: the introduction of ticket zones, which remain in use today.

[edit] London Regional Transport

In 1984 Margaret Thatcher's Conservative Government removed London Transport from the GLC's control, replacing it with London Regional Transport (LRT) on 19 June 1984 – a statutory corporation for which the Secretary of State for Transport was directly responsible. The Government planned to modernise the system while slashing its subsidy from taxpayers and ratepayers. As part of this strategy London Underground Limited was set up on 1 April 1985 as a wholly owned subsidiary of LRT to run the network.

The prognosis for LRT was good. Oliver Green, the then Curator of the London Transport Museum, wrote in 1987:

In its first annual report, London Underground Ltd was able to announce that more passengers had used the system than ever before. In 1985–86 the Underground carried 762 million passengers – well above its previous record total of 720 million in 1948. At the same time costs have been significantly reduced with a new system of train overhaul and the introduction of more driver-only operation. Work is well in hand on the conversion of station booking offices to take the new Underground Ticketing System (UTS)...and prototype trials for the next generation of tube trains (1990) stock started in late 1986. As the London Underground celebrates its 125th anniversary in 1988, the future looks promising.[22]

However, cost-cutting didn't come without critics. At 19:30 on 18 November 1987, a massive fire swept through the King's Cross St Pancras tube station, the busiest station on the network, killing 31 people. It later turned out that the fire had started in an escalator shaft to the Piccadilly Line, which was burnt out along with the top level (entrances and ticket hall) of the deep-level tube station. The escalator on which the fire started had been built just before World War II. The steps and sides of the escalator were partly made of wood, meaning that they burned quickly and easily. Although smoking was banned on the subsurface sections of the London Underground in February 1985 as a consequence of the Oxford Circus fire, the fire was most probably caused by a commuter discarding a burning match, which fell down the side of the escalator onto the running track (Fennell 1988, p. 111). The running track had not been cleaned in some time and was covered in grease and fibrous detritus. The Member of Parliament for the area, Frank Dobson, informed the House of Commons that the number of transportation employees at the station, which handled 200,000 passengers every day at the time, had been cut from 16 to ten, and the cleaning staff from 14 to two.[23] The tragic event led to the abolition of all wooden escalators at all Underground stations and pledges of greater investment.

In 1994, with the privatisation of British Rail, LRT took control of the Waterloo and City Line, incorporating it into the Underground network for the first time. This year also saw the end of services on the little used Epping-Ongar branch of the Central Line and the Aldwych branch of the Piccadilly Line after it was agreed that necessary maintenance and upgrade work would not be cost-effective.

In 1999 the Jubilee Line Extension to Stratford in London's East End was completed. This plan included the opening of a completely refurbished interchange station at Westminster. The Jubilee line's old terminal platforms at Charing Cross were closed but maintained operable for emergencies and film shoots.

[edit] Public Private Partnership

Transport for London (TfL) replaced LRT in 2000, a development that coincided with the creation of a directly-elected Mayor of London and the London Assembly.

In January 2003 the Underground began operating as a Public-Private Partnership (PPP), whereby the infrastructure and rolling stock were maintained by two private companies (Metronet and Tube Lines) under 30-year contracts, while London Underground Limited remained publicly owned and operated by TfL.

Supporters of the change claimed that the private sector would eliminate the inefficiencies of public-sector enterprises and take on the risks associated with running the network, while opponents said that the need to make profits would reduce the investment and public-service aspects of the Underground. The scheme was put in jeopardy when Metronet, which was responsible for two-thirds of the network, went into administration on 18 July 2007[24][25] after costs for its projects spiralled out of control. The case for PPP was further weakened a year later when it emerged that Metronet's demise had cost the UK government £2 billion. The five private companies that made up the Metronet alliance had to pay £70m each towards paying off the debts acquired by the consortium. But under a deal struck with the Government in 2003 the companies were protected from any further liability. The UK taxpayer therefore had to foot the rest of the bill. This undermined the argument that the PPP would place the risks involved in running the network into the hands of the private sector.[26]

TfL took over the responsibilities of Metronet following its collapse. The Government made concerted efforts to find another private firm to fill the void but none came forward. TfL and the Department for Transport have since agreed to allow TfL to continue operating the areas that were formerly the responsibility of Metronet. An independent panel will review TfL's investment programme. This leaves two-thirds of the Underground network completely under the control of TfL. The Secretary of State for Transport, at the time Lord Adonis, hinted that a separate arrangement might be made for the Bakerloo line at a later date.[27]

Maintenance on the Jubilee, Northern and Piccadilly lines remained the responsibility of Tube Lines, although this too has not been without controversy. The relationship between London Underground and Tube Lines deteriorated with disagreements over priorities, estimates and whether Tubes Lines had sufficient funds to meet its commitments.[28] In late 2009 Tube Lines encountered a funding shortfall for their upgrades and requested that TfL provide an additional £1.75billion to cover the shortfall; TfL refused and referred the matter to the PPP arbiter who stated that £400million should be provided[29]. There had been many discussions over the future of the company in the second review period and it was announced on 7 May 2010 that TfL had agreed to buy the shares of Bechtel and Amey (Ferrovial) from Tube Lines for £310m[30]. Combined with the takeover of Metronet, this means that the PPP is dead as all maintenance is now managed in-house by TfL[30].

The National Audit Office in a 2004 report on the PPP stated that the Department of Transport, London Regional Transport and London Underground Limited spent £180m in structuring, negotaiting and implementing the PPP and also reimbursed £275m of bid costs to the winning bidders

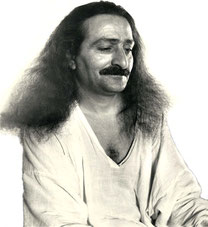

Meher Baba's Life & Travels

Meher Baba's Life & Travels